Publisher Summary

This chapter describes the physiological study of cells and fluids. The cytoplasm of a cell surrounds the nucleus and the organelles, and is bounded by a membrane. In histological sections stained with the standard hematoxylin and eosin stains, it appears as a faintly purple-staining, slightly granular background. Tests with intracellular probes show it to be either a gel or a sol and to be more gel-like near the cell membrane. It contains cell water, proteins, small organic molecules, and some inorganic ions. Cells are usually separated from each other by a space about 20 nm wide filled with proteoglycans. There are three types of junction frequently seen between mammalian cells: (1) desmosomes, (2) tight junctions, and (3) gap junctions. Within the cytoplasm are varying numbers of organelles, each enclosed by membrane material. There is continuity between the outer layer of the nuclear membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum. Enamel fluid is more of an enigma. It is a fluid that has been observed to collect in droplets when a layer of oil is placed over the enamel surface of the teeth of anaesthetized animals.

The cell and its contents

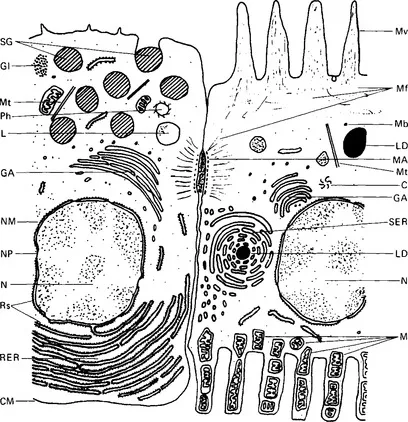

Physiology is the study of how living creatures live; human physiology the study of the physical and chemical processes that make up the life of man. It is based on anatomy, the study of structure or morphology; on histology, or micro-morphology; on biochemistry, the study of the chemical processes of life; and on biophysics, the study of the physical parameters of living organisms. In considering physiological principles it is helpful to look first at the basic rules governing the function of all body cells, then to apply these to the operation of the organs of the body, and finally to apply them to the functioning of the body as a whole. This book begins, then, by considering the normal structure of cells, their substructures or organelles, and the ways in which these contribute to the functioning of the cells. Fig. 1.1 shows two adjacent half cells containing most of the possible organelles in some of their typical arrangements. These are hypothetical examples since it is very unlikely that any cell would contain all these organelles.

Figure 1.1 Diagram of two half cells as seen under the electron microscope. These are not actual cells, but have been drawn to demonstrate a number of organelles. Key: C, centriole; CM, cell membrane; GA, Golgi apparatus; GI, glycogen granules; L, lysosome; LD, lipid droplet; M, mitochondria; MA, macula adhaerens; Mf, microfilaments; Mt, microtubules; Mb, microbody; Mv, microvillus; N, nucleus; NM, nuclear membrane; NP, nuclear pore; Ph, phagosome; RER, rough endoplasmic reticulum; Rs, ribosomes; SER, smooth endoplasmic reticulum; SG, secretory granule.

The cytoplasm of a cell surrounds the nucleus and the organelles, and is bounded by a membrane. In histological sections stained with the standard haematoxylin and eosin stains it appears as a faintly purple-staining, slightly granular background; under the electron microscope it appears clear (or electron-lucent) with varying degrees of fine electron-dense granulation and some fine filaments or rods. Tests with intracellular probes show it to be either a gel or a sol, and to be more gel-like near the cell membrane. It contains cell water, proteins, small organic molecules, and some inorganic ions. Most cells contain about 85% of water. The protein constituents are in various degrees of aggregation. Some are highly structured to form filaments, as in muscle cells. The cell pH is usually slightly acid, and under these conditions most cell proteins behave as anions and contribute to the total anionic charge of the cell. The other major cell anions are chloride, phosphate and hydrogen carbonate. Balancing the anionic charge are the inorganic cations, principally potassium ions.

The cell membrane

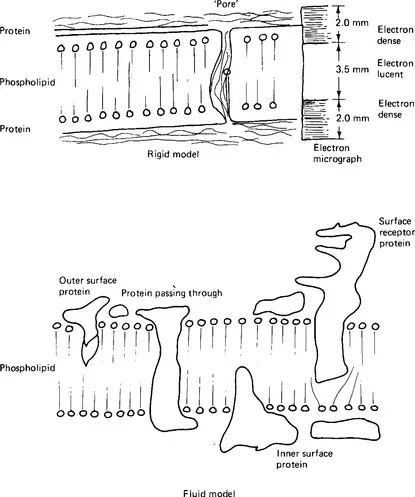

The limiting membrane of the cell, often called the plasma membrane, has been much studied because the properties of this membrane dictate what may enter or leave the cell and hence maintain the identity of the cell contents. Viewed with the electron microscope the typical membrane appears as two electron-dense lines separated by an electron-lucent zone. Membranes of this appearance are often termed ‘unit membranes’. The membrane has an average width, after fixation, of around 7.5 nm and each of the electron-dense lines is approximately 2.0nm wide. Chemical analysis of membrane material and experiments with lipids suggested that a flexible membrane-like structure could be formed from a bimolecular layer of lipid molecules orientated with their hydrophobic fatty acid side chains inwards towards each other, and their hydrophilic phosphate or basic groups pointing outwards. Indeed, it was suggested at one time that the cell membrane was not a true morphological structure but simply a lipid layer on the cytoplasmic surface. However, further study of the properties of membranes showed that they were made up of a bimolecular layer of phospholipid covered on each side by a protein layer; this model accords with the appearance seen with the electron microscope (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Models of the cell membrane. (a) The rigid model with a pore filled with protein; on the right, its appearance under the electron microscope. (b) A section through a fluid membrane model at a single instant of time, a protein molecule spanning the membrane again providing a pore for water and small solutes to cross the membrane.

It is, however, very simple, and explains only the bounding function of the membrane. Cell membranes have other properties also. They allow the passage of lipid-soluble substances and, to a lesser extent, small water-soluble substances. The latter property implies that the phospholipid layer is not continuous, but interrupted by ‘pores’ of small size. Studies of the sizes of water-soluble substances able to cross membranes permit estimation of the effective pore size - around 0.70-0.85 nm in a red blood cell membrane. Comparison of rates of diffusion leads to a calculation that 0.06% of the surface area of these particular membranes is occupied by the pores. No actual pores have been detected by electron microscopy even though pores of this size and density ought to be occasionally visible. Such pores are probably not actual holes in the membrane but areas in which water-soaked hydrophilic proteins penetrate the lipid layer. The membrane is able to permit certain ions and molecules to pass selectively at rates greatly in excess of those predicted from diffusion data. This property is linked with protein, or, more precisely, carrier or enzyme activity. This selective movement of substances in or out of certain cells can be modified precisely and in particular time sequences. Further, certain substances pass through the membrane against concentration and electropotential gradients, implying that the membrane is capable of utilising energy to perform work. All these properties suggest that the membrane contains proteins with specific binding functions. In this respect these proteins resemble enzymes and so they have sometimes been called permeases. Parts of the cell membrane in some instances may enclose external matter and then incorporate it into the cell; other parts of the membrane may apparently be new-formed from fusion of the membranes of organelles. Any model which suggests complete uniformity of the cell membrane is therefore likely to be misleading.

A number of modifications to the original model have been suggested. None is entirely satisfactory but each presents solutions to some of the difficulties with the original model. It is clear that membranes differ from one type of cell to another and also from point to point on the surface of one cell. For example, the protein to lipid ratio is different in red blood cell membranes from that in the membranes of nerve cells; indeed, the composition of the lipid material itself is different. Membranes vary in thickness and in biological activity. The current model is of a fluid structure in which the lipid and protein molecules are relatively mobile, so that the appearance of the membrane differs from moment to moment. The structure may become more stable or more rigid when particular protein units are performing particular functions. Chemical substances or drugs may cause changes in the movement of membrane components. Some proteins may extend across the membrane, some may travel from one side to the other, whilst still others may be associated with only the inner or the outer side of the membrane.

Junctions between cells

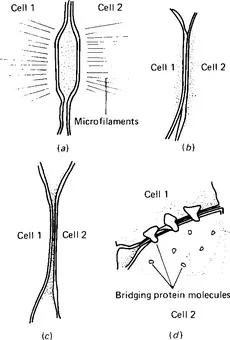

Cells are usually separated from each other by a space about 20nm wide filled with proteoglycans. However, a number of membrane specialisations provide either a means of attaching one cell to another or of barring the space between the cells (Fig. 1.3). The term zonule is used to describe a junction which extends round a cell, and the term macula to describe a junction involving only a small area of cell membrane. Either of these may be ‘adhaerens’, so that the cells are simply attached to each other, or ‘occludens’, when the attachment effectively obliterates the intercellular space.

Figure 1.3 Types of cell junction, (a) The macula adhaerens - a desmosome, (b) a zonula occludens - a tight junction, (c) a close or gap junction, (d) a close or gap junction at higher magnification. The protein plugs joining the two cells can be seen on the inner face of the membrane of the cell on the right.

There are three types of junction frequently seen between mammalian cells: desmosomes, tight junctions, and gap junctions. The desmosome (Fig. 1.3a) is a macula adhaerens. It is a small discoid attachment between neighbouring cells, found particularly in epithelial tissues. Dense clusters of filaments are situated in a pair of electron-dense spots on adjacent membranes of two cells and the space between the cells is filled with fibrous material. A tight junction (Fig. 1.3b) is a zonula occludens, usually extending round a cell. In a tight junction the membranes of the two cells are fused together so that their outer layers become one; the membrane thus appears to have three electron-dense lines separated by two e...