Cyclura

Natural History, Husbandry, and Conservation of West Indian Rock Iguanas

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Cyclura

Natural History, Husbandry, and Conservation of West Indian Rock Iguanas

About this book

Rock iguanas of the West Indies are considered to be the most endangered group of lizards in the world. They are a flagship species in the Caribbean and on most islands are the largest native land animals. Unfortunately, human encroachment and introduced animals have brought this species to the brink of extinction. Cyclura: Natural History, Husbandry, and Conservation of the West Indian Iguanas is the first book to combine the natural history and captive husbandry of these remarkable reptiles, while at the same time outlining the problems researchers and conservationists are battling to save these beautiful, iconic animals of the Caribbean islands.Authors Jeffrey Lemm and Allison Alberts have been studying West Indian iguanas for nearly 20 years in the wild and in captivity; their experiences with wild iguanas and their exquisite photos of these charismatic lizards in the wild make this book a must-have for reptile researchers, academics and enthusiasts, as well as anyone interested in nature and conservation.- Includes chapters with contributions by leading experts on rock iguana taxonomy, nutrition, and diseases- Features color photos of all taxa, including habitat and captive shots- Provides easily understandable and usable information gleaned from experience and hands-on reptile research

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Catherine L. Stephen

Outline

Evolution on Islands

|

| FIGURE 1.1 Grand Cayman Blue iguanas are believed to be relatives of iguanas that rafted to the Cayman Islands from Cuba. |

Cyclura’s Wild Ride

|

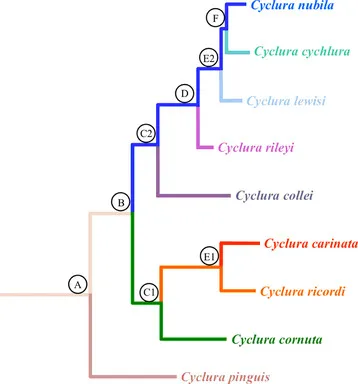

| FIGURE 1.2 Evolutionary relationships of the Cyclura species. Letters mark each divergence (node). Each species is color coded to match their distribution in Figure 1.3. |

|

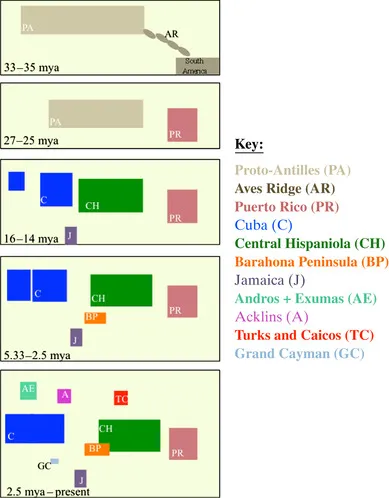

| FIGURE 1.3 A chronological series of some of the geologic changes in the Caribbean from the Oligocene–Eocene transition to the present (based on Iturralde-Vinent, 2006). Each island (or island group) is color coded to indicate the Cyclura species occurring there. |

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Table of Contents

- Cyclura

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Chapter 1. Evolution and Biogeography

- Chapter 2. Species Accounts

- Chapter 3. Natural History

- Chapter 4. Husbandry

- Chapter 5. Nutrition

- Chapter 6. Health and Medical Management

- Chapter 7. Conservation

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index