- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Theory and Practice of the Dewey Decimal Classification System

About this book

The Dewey Decimal Classification system (DDC) is the world's most popular library classification system. The 23rd edition of the DDC was published in 2011. This second edition of The Theory and Practice of the Dewey Decimal Classification System examines the history, management and technical aspects of the DDC up to its latest edition. The book places emphasis on explaining the structure and number building techniques in the DDC and reviews all aspects of subject analysis and number building by the most recent version of the DDC. A history of, and introduction to, the DDC is followed by subject analysis and locating class numbers, chapters covering use of the tables and subdivisions therein, multiple synthesis, and using the relative index. In the appendix, a number of academically-interesting questions are identified and answered.

- Provides a comprehensive chronology of the DDC from its inception in 1876, to the present day

- Describes the governance, revision machinery and updating process

- Gives a table of all editors of the DDC

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Theory and Practice of the Dewey Decimal Classification System by M. P. Satija in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Filología & Biblioteconomía y ciencia de la información. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A brief history of the Dewey Decimal Classification

Abstract:

This chapter outlines the history of the DDC since its conception in 1873 which worked towards its first publication in 1876. Now in its 23rd edition (published in 2011); the DDC describes the mechanism and disadvantages of ‘fixed location’ classification systems prevalent before Melvil Dewey. In addition this chapter will review the features and changes in all previous editions, in chronological order, detailing their respective editors. Finally, the history and features of the abridged, school and the electronic editions of the system will be examined, and will highlight the DDC’s major contribution to the science and art of classification – proving that it is the mother of all modern library classification systems.

Key words

Abridged Dewey

Dewey Decimal Classification (history)

Dewey for schools

editions of the DDC

fixed location systems

modern library classifications

online classification

WebDewey

In the aftermath of the nineteenth-century industrial revolution came the rise of capitalism, democracy and expansion of education; books and libraries began to be looked upon as instruments of social change. Democratised libraries were thrown open to all sections of society. To meet the new challenge and fulfil the expectations of a much aware society, libraries underwent many changes. Open access to the collection was introduced, thus allowing readers to browse freely through stacks of books. This change required more scientific and efficient methods for the cataloguing, storage, location and re-shelving of books than had been practised up to that point in time.

The library classification systems – in fact the methods for arranging books–prevalent till the last quarter of the nineteenth century are now called ‘fixed location systems’. These were so styled because though items in a collection were gathered into broad subject categories their location was fixed on the shelves until the next reclassification of the library. In such systems items were arranged according to their accession number within broad classes. For instance, say that Q represented physics, then Q2.3.14 would be the fourteenth book on the third shelf of the second book case for the physics books. Thus the number a book bore and the location it ended up in were accidental; they did not take into account the internal relationships of physics. This caused many difficulties. For instance, when the space allotted to physics was filled, new books had to be placed elsewhere (thus breaking the subject grouping), or a range located elsewhere in the library could be dedicated to physics, or the nearest range occupied by books of some other subject would have to be vacated, which would require giving new numbers to all the books shifted. Thus it was a problem of hospitality, to use modern terminology.

When Melvil Dewey (1851–1931) became a student assistant in the Amherst College Library in 1870, he was confronted with the problems attendant upon fixed location systems. His economizing mind hated the wastage and ordeal of reclassifying books. He turned to devising a notation that could secure subject collocation forever without ever having to reclassify. His arrangement was to be by subject, of course. Here there was no problem, as there were many ways to organise knowledge and several were in vogue. The problem was to discover a device that would mechanise such a system and locate the appropriate place for a new book without disturbing other books on the shelves. The malady had been diagnosed, and Dewey knew that a cure was near. The problem possessed him day in, day out. He visited many American libraries (especially in New England and New York) in search of a solution, corresponded with many people and experimented with different kinds of notation. An elegant solution occurred to him early in 1873, not at his desk but in a church on a Sunday morning. Dewey recounted the event half a century later:

For months I dreamd night and day that there must be somewhere a satisfactory solution. In the future wer thousands of libraries, most of them in charje of those with little skil or training. The first essential of the solution must be the greatest possible simplicity. The proverb said ‘simple as a, b, c,’ but still simpler than that was 1, 2, 3. After months of study, one Sunday during a long sermon by Pres. Stearns, while I lookt steadfastly at him without hearing a word, my mind absorbed in the vital problem, the solution flasht over me so that I jumpt in my seat and came very near shouting ‘Eureka’! It was to get absolute simplicity by using the simplest known symbols, the arabic numerals as decimals, with the ordinary significance of nought, to number a classification of all human knowledge in print; this supplemented by the next simplest known symbols, a, b, c, indexing all heds of the tables so that it would be easier to use a classification with 1000 heds so keyd than to use the ordinary 30 or 40 heds which one had to study carefully before using (Dewey, 1920 – original simplified spellings have been retained).

On 8 May 1873, Dewey (then 21 years old) presented his idea to the Amherst College Library Committee, won its approval and set out to develop a classification for use by the students and faculty of the College. The organisation of knowledge that he chose to use was devised by William Torrey Harris for the St Louis Public School Library catalogue.

Dewey had invented a system that was mechanical, ductile and capable of arranging books according to their contents. Thus he had relieved book classification from the shackles of a purely arbitrary and accidental notation and saved his fellow librarians much labour and frustration. But beyond this, he had instigated a new era of bibliographic classification.

The scheme was applied to the library of Amherst College, and later published anonymously in 1876 under the title A Classification and Subject Index for Cataloging and Arranging the Books and Pamphlets of a Library. The booklet consisted of 44 pages, including the list of 889 three-digit numbers, introduction and the index. Dewey saw to it that several hundred copies were printed and distributed to strategic places. It received wide publicity in the same year when specimen classes and an even longer introduction were published in Public Libraries in the United States by the US Bureau of Education as a volume on the state of the art of librarianship intended to be available at the Philadelphia Conference of Librarians to be held that year. It is inevitable that he discussed the classification with the conference participants. Acclaim was instantaneous, though some feared it to be too excessively detailed to be useful to libraries. It was discussed again at the International Conference of Librarians held in London in 1877 although it would be a while before the British embraced the DDC.

As we have seen, the classification of books was mainly by subject before Dewey, and Dewey had borrowed an already existing system. A type of decimal notation was also being applied in some libraries. Even so, what Dewey did was new, fresh and marked a clean break with the past. Over and above the subject arrangement, the Indo-Arabic numerals used as decimal fractions to systematically mark the contents of books provided many far-reaching and unintended advantages. Besides providing infinite (always needed) hospitality to new books and new subjects, the notation also depicted the hierarchy of subjects. The index of subject headings provided at the end of the First Edition has evolved into what is now known as the ‘relative index’, a tool that is almost as large as the schedules and indispensable for classifiers. Classification by discipline, depiction of hierarchy of subjects, provision of infinite hospitality and the relative index are considered to be Dewey’s main and revolutionary contributions to library classification.

The Second Edition, entitled Decimal Classification and Relative Index, appeared in 1885. W.S. Biscoe (1853–1933), who had followed Dewey to Columbia College, assisted in its development. This edition was copyrighted by the Library Bureau, a library supply company founded primarily by Dewey in 1882. It was an important edition in many respects. In the schedules it was more than 11 times larger than the First Edition as far as the number of pages were concerned; it was much larger than that as far as printed numbers and numbers made possible by synthesis were concerned. Conceptually, it was hundreds of times larger. It demonstrated for the first time the potential of a notation composed of decimal fractions by extending numbers beyond three digits.

The Second Edition contained many changes. To ward off fear among librarians that the scheme was unstable and that each new edition might entail reclassification (thus displaying no net gain over fixed location systems), Dewey promised in the introduction that the numbers and their meanings were linked forever. Henceforth there would be no changes in the existing numbers, only numbers added for new subjects. The promise relieved classifiers and was the basis of an important policy, the well-known integrity of numbers policy, the ghost of which haunted the revision of the first 14 editions and is still felt. It continues to influence every revision, and is a weighty consideration though not the overriding one. Keeping pace with knowledge is now the transcendent policy.

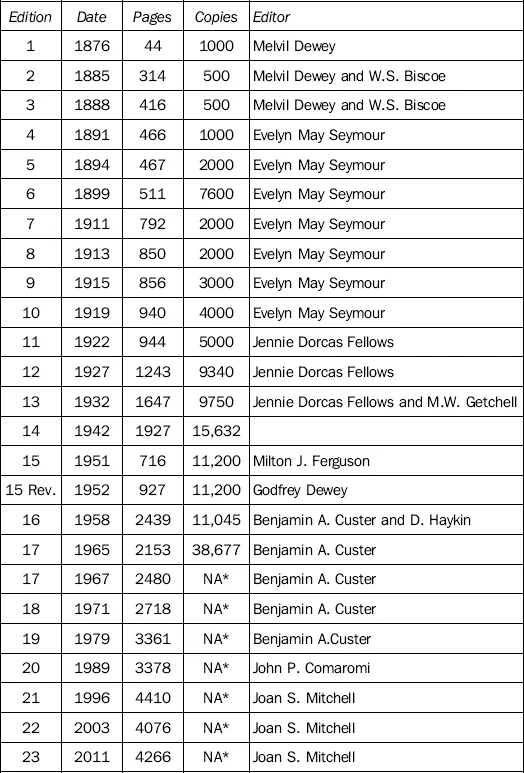

On the average 23 editions of the DDC have appeared at irregular intervals. In the early years the date of publication was based on when the previous edition ran out. Table 1.1 provides a thumbnail publishing history of the DDC.

Table 1.1

A brief history on the publication of the Dewey Decimal Classification System.

*Information not available

While Dewey was alive he personally oversaw editorial production and controlled money matters. To be sure, a formal editor developed the DDC, dotting the i’s and curling the q’s. After the death of Dewey in 1931 the Thirteenth Edition was published in 1932 posthumously. By the Fourteenth Edition (1942) the growth had become lopsided and uneven, providing too little for some classes and too much for others; it was so large that many libraries not needing such detail began to complain in earnest. It was decided to bring out a streamlined edition. The Fifteenth Edition was contemplated as the ‘Standard Edition’; it was intended for a collection of any size up to 200,000 documents; all classes were to be evenly developed and in a stable order. It appeared in 1951; it had been edited by Milton J. Ferguson after Esther Potter and her assistants at the Library of Congress had proved incapable of concluding the edition. Though an elegant publication it was worse than a failure: it was a disaster. It was reduced to one-tenth the conceptual size of its predecessor. In a spurt of modernisation the integrity of numbers policy was grossly violated. Relocations abounded – a thousand at least; synthesis of numbers, except by form divisions, was totally absent (a history or geography for most of the world could not have a DDC number built for it!).

It was the first real revision of the DDC since 1885, but it was not what librarians wanted. Sensing the failure, Forest Press hurried a revised Fifteenth Edition into print, but most of the revision occurred in the beefed-up index that replaced the unbelievably bad index that was in the Standard Edition (and which had been prepared by someone outside the DDC editorial office).

Reissuing the Fifteenth Edition in a revised version had used up a good deal of money and there was not enough to prepare the Sixteenth. To the aid of the DDC came the Library of Congress (LC), which agreed to support the production of the Sixteenth Edition provided (1) it could appoint the editor and (2) the Lake Placid Club Education Foundation would underwrite a reasonable amount of the editorial costs. This was agreed to, and David J. Haykin became the next editor of the DDC. He soon came into conflict with the Decimal Classification Section of the Library of Congress (where DDC numbers were assigned to LC cards), with the Editorial Policy Committee and with an advisory committee representing practising librarians since he was of the keeping-pace-with knowledge camp, but these groups were almost all solidly in the integrity-of-numbers camp. He was forced to resign in 1956, to be replaced by Benjamin A. Custer (1912–97). The eighth editor, though progressive by nature, was a diplomat by instinct and brought the Sixteenth Edition to conclusion in 1958 in the form that the integrity-of-numbers camp desired.

The Sixteenth Edition was in line with the Fourteenth, even though 45 per cent of the relocations made for the Fifteenth Edition were retained. Its size had grown to two volumes, the second volume containing the index and the table of form divisions. It continued the tradition begun in the Revised Fifteenth Edition of a binding colour that no other edition possessed: the Fifteenth Edition had been sea green, the Revised Fifteenth a grey blue, the Sixteenth brick red, the Seventeenth forest green, the Eighteenth bright blue, the Nineteenth grey with maroon cartouches, the Twentieth brick red, the Twenty-first blue and the Twenty-second green and black, and the Twenty-third maroon and black.

The Sixteenth Edition was important in many respects. It was a confluence of conservative and progressive policies. Custer had preserved the best of the conservative spirit while at the same time accommodating the advances in knowledge by retaining half of the modernisations of the Fifteenth Edition and introducing the concept of the phoenix schedule. A phoenix schedule was a complete revision of an area, usually a division or several sections; the old schedule is removed and a new one instituted in its place retaining only the heading number; if a topic was at the same number in both editions, it was incidental. Phoenix schedules aimed at rectification of the schedules and tables in small but very potent doses, thus rendering the changes easily manageable. Since the Nineteenth Edition there have been no more than two phoenix schedules per edition. (What a phoenix may cover, however, va...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- List of abbreviations

- List of figures and tables

- About the author

- Chapter 1: A brief history of the Dewey Decimal Classification

- Chapter 2: Governance and revision of the DDC

- Chapter 3: Introduction to the text in four volumes

- Chapter 4: Basic plan and structure

- Chapter 5: Subject analysis and locating class numbers

- Chapter 6: Tables and rules for precedence of classes

- Chapter 7: Number-building

- Chapter 8: Use of Table 1: standard subdivisions

- Chapter 9: Use of Table 2: geographical areas, historical periods and persons

- Chapter 10: Use of Table 3: subdivisions for the arts, individual literatures and for literary forms

- Chapter 11: Use of Table 4 and Table 6: subdivisions of individual languages and their language families

- Chapter 12: Use of Table 5: ethnic and national groups

- Chapter 13: Multiple synthesis

- Chapter 14: Using the relative index

- Appendix 1: A broad chronology of the DDC

- Appendix 2: Table of DDC editors

- Appendix 3: Revision tutorial: questions

- Appendix 4: Revision tutorial: answers

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Useful DDC websites

- Index