Robert R. Crichton, Batiment Lavoisier, Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

Introduction: Which Metals Ions and Why?

Some Physicochemical Considerations on Alkali Metals

Na+ and K+ – Functional Ionic Gradients

Mg2+ – Phosphate Metabolism

Ca2+ and Cell Signalling

Zinc – Lewis Acid and Gene Regulator

Iron and Copper – Dealing with Oxygen

Ni and Co – Evolutionary Relics

Mn – Water Splitting and Oxygen Generation

Mo and V – Nitrogen Fixation

Introduction: Which Metals Ions and Why?

In the companion book to this one, ‘Biological Inorganic Chemistry 2nd edition’ (Crichton, 2011), we explain in greater detail why life as we know it would not be possible with just the elements found in organic chemistry – namely carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur. We also need components of inorganic chemistry as well, and in the course of evolution nature has selected a number of metal ions to construct living organisms. Some of them, like sodium and potassium, calcium and magnesium, are present at quite large concentrations, constituting the so-called ‘bulk elements’, whereas others, like cobalt, copper, iron and zinc, are known as ‘trace elements’, with dietary requirements that are much lower than the bulk elements.

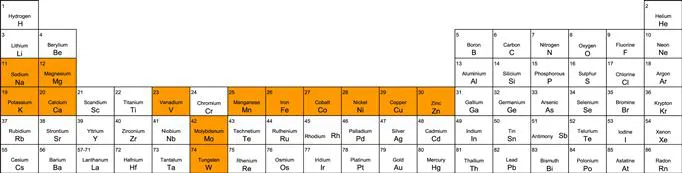

Just six elements – oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, calcium and phosphorus – make up almost 98.5% of the elemental composition of the human body by weight. And just 11 elements account for 99.9% of the human body (the five others are potassium, sulfur, sodium, magnesium and chlorine). However, between 22 and 30 elements are required by some, if not all, living organisms, and of these are quite a number are metals. In addition to the four metal ions mentioned above, we know that cobalt, copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, vanadium and zinc are essential for humans, while tungsten replaces molybdenum in some bacteria. The essential nature of chromium for humans remains enigmatic.

Just why these elements out of the entire periodic table (Figure 1.1) have been selected will be discussed here. However, their selection was presumably based not only on suitability for the functions that they are called upon to play in what is predominantly an aqueous environment, but also on their abundance and their availability in the earth’s crust and its oceans (which constitute the major proportion of the earth’s surface).

FIGURE 1.1 An abbreviated periodic table of the elements showing the metal ions discussed in this chapter.

The 13 metal ions that we will discuss here fall naturally into four groups based on their chemical properties. In the first, we have the alkali metal ions Na+ and K+. Together with H+ and Cl−, they bind weakly to organic ligands, have high mobility, and are therefore ideally suited for generating ionic gradients across membranes and for maintaining osmotic balance. In most mammalian cells, most K+ is intracellular, and Na+ extracellular, with this concentration differential ensuring cellular osmotic balance, signal transduction and neurotransmission. Na+ and K+ fluxes play a crucial role in the transmission of nervous impulses both within the brain and from the brain to other parts of the body.

The second group is made up by the alkaline earths, Mg2+ and Ca2+. With intermediate binding strengths to organic ligands, they are, at best semi-mobile, and play important structural roles. The role of Mg2+ is intimately associated with phosphate, and it is involved in many phosphoryl transfer reactions. Mg-ATP is important in muscle contraction, and also functions in the stabilisation of nucleic acid structures, as well as in the catalytic activity of ribozymes (catalytic RNA molecules). Mg2+ is also found in photosynthetic organisms as the metal centre in the light-absorbing chlorophylls. Ca+ is a crucial second messenger, signalling key changes in cellular metabolism, but is also important in muscle activation, in the activation of many proteases, both intra- and extracellular, and as a major component of a range of bio-minerals, including bone.

Zn2+, which is arguably not a transition element,1 constitutes the third group on its own. It is moderate to strong binding, is of intermediate mobility and is often found playing a structural role, although it can also fulfil a very important function as a Lewis acid. Structural elements, called zinc fingers, play an important role in the regulation of gene expression.

The other eight transition metal ions, Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni, V and W form the final group. They bind tightly to organic ligands and therefore have very low mobility. Since they can exist in various oxidation states, they participate in innumerable redox reactions, and many of them are involved in oxygen chemistry. Fe and Cu are constituents of a large number of proteins involved in electron transfer chains. They also play an important role in oxygen-binding proteins involved in oxygen activation as well as in oxygen transport and storage. Co, together with another essential transition metal, Ni, is particularly important in the metabolism of small molecules like carbon monoxide, hydrogen and methane. Co is also involved in isomerisation and methyl transfer reactions. A major role of Mn is in the catalytic cluster involved in the photosynthetic oxidation of water to dioxygen in plants, and, from a much earlier period in geological time, in cyanobacteria. Mo and W enzymes contain a pyranopterindithiolate cofactor, while nitrogenase, the key enzyme of N2 fixation contains a molybdenum–iron–sulfur cofactor, in which V can replace Mo when Mo is deficient. Other V enzymes include haloperoxidases. To date no Cr-binding proteins have been found, adding to the lack of biochemical evidence for a biological role of the enigmatic Cr.

Some Physicochemical Considerations on Alkali Metals

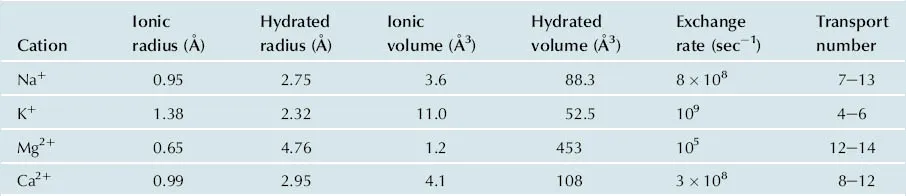

Before considering, in more detail, the roles of the alkali metals, Na+ and K+, and the alkaline earth metals, Mg2+ and Ca2+, it may be useful to examine some of their physicochemical properties (Table 1.1). We can observe, for example that Na+ and K+ have quite significantly different unhydrated ionic radii, whereas, the hydrated radii are much more similar. It therefore comes as no surprise that the pumps and channels which carry them across membranes, and which can easily distinguish between them, as we will see shortly, transport the unhydrated ions. Although not indicated in the table, it is clear that Na+ is invariably hexa-coordinate, whereas K+ and Ca2+ can adjust to accommodate 6, 7 or 8 ligands. As we indicated above, both Na+ and K+ are characterised by very high solvent exchange rates (around 109/s), consistent with their high mobility and their role in generating ionic gradients across membranes. In contrast, the mobility of Mg2+ is some four orders of magnitude slower, consistent with its essentially structural and catalytic. Perhaps surprisingly, Ca2+ has a much higher mobility (3 × 108/s), which explains why it is involved in cell signalling via rapid changes on Ca2+ fluxes.

TABLE 1.1

Properties of Common Biological Cations

(From Maguire and Cowan, 2002).

The selective binding of Ca2+ by biological ligands compared to Mg2+ can be explained by the difference in their ionic radius, as we pointed out above. Also, for the smaller Mg2+ ion, the central field of the cation dominates its coordination sphere, whereas for Ca2+, the second and possibly even the third, coordination spheres have an important influence resulting in irregular coordination geometry. This allows Ca2+, unlike Mg2+ to bind to a large number of centres at once.

The high charge density on Mg2+ as a consequence of its small ionic radius ensures that it is an excellent Lewis acid in reactions notably involving phosphoryl transfers and hydrolysis of phosphoesters. Typically, Mg2+ functions as a Lewis acid, either by activating a bound nucleophile to a more reactive anionic form (e.g. water to hydroxide anion), or by stabilising an intermediate. The invariably hexacoordinate Mg2+ often participates in structures where the metal is bound to four or five ligands from the protein and a phosphorylated substrate. This leaves one or two coordination positions vacant for occupation by water molecules, which can be positioned in a particular geometry by the Mg2+ to participate in the catalytic mechanism of the enzyme.