eBook - ePub

About this book

Neuroimaging, Part Two, a volume in The Handbook of Clinical Neurology series, illustrates how neuroimaging is rapidly expanding its reach and applications in clinical neurology. It is an ideal resource for anyone interested in the study of the nervous system, and is useful to both beginners in various related fields and to specialists who want to update or refresh their knowledge base on neuroimaging.

This second volume covers imaging of the adult spine and peripheral nervous system, as well as pediatric neuroimaging. In addition, it provides an overview of the differential diagnosis of the most common imaging findings, such as ring enhancement on MRI, and a review of the indications for imaging in the most frequent neurological syndromes.

The volume concludes with a review of neuroimaging in experimental animals and how it relates to neuropathology. It brings broad coverage of the topic using many color images to illustrate key points. Contributions from leading global experts are collated, providing the broadest view of neuroimaging as it currently stands.

For a number of neurological disorders, imaging is not only critical for diagnosis, but also for monitoring the effect of therapies, with the entire field moving from curing diseases to preventing them. Most of the information contained in this volume reflects the newness of this approach, pointing to the new horizon in the study of neurological disorders.

- Provides a relevant description of the technologies used in neuroimaging, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and several others

- Discusses the application of these techniques to the study of brain and spinal cord disease

- Explores the indications for the use of these techniques in various syndromes

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Section 7

Pediatric neuroimaging

Chapter 57

Normal development

Nadine Girard1,2,*; Meriam Koob3; Herv Brunel1 1 Neuroradiology Service, Hôpital la Timone, Marseille, France

2 Aix Marseille Université, Marseille, France

3 Pediatric Radiology Imaging Service, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Strasbourg, Hôpital de Hautepierre and Laboratoire ICube, Université de Strasbourg-CNRS, Strasbourg, France

* Correspondence to: Nadine Girard, MD, Professor of Neuroradiology, Service de Neuroradiologie, Hôpital la Timone, APHM, 264 rue Saint Pierre, 13385 Marseille CEDEX 05, France. Tel: + 33-4-1329061, Fax: + 33-4-13429093 email address: [email protected]

2 Aix Marseille Université, Marseille, France

3 Pediatric Radiology Imaging Service, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Strasbourg, Hôpital de Hautepierre and Laboratoire ICube, Université de Strasbourg-CNRS, Strasbourg, France

* Correspondence to: Nadine Girard, MD, Professor of Neuroradiology, Service de Neuroradiologie, Hôpital la Timone, APHM, 264 rue Saint Pierre, 13385 Marseille CEDEX 05, France. Tel: + 33-4-1329061, Fax: + 33-4-13429093 email address: [email protected]

Abstract

Numerous events are involved in brain development, some of which are detected by neuroimaging. Major changes in brain morphology are depicted by brain imaging during the fetal period while changes in brain composition can be demonstrated in both pre- and postnatal periods. Although ultrasonography and computed tomography can show changes in brain morphology, these techniques are insensitive to myelination that is one of the most important events occurring during brain maturation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is therefore the method of choice to evaluate brain maturation. MRI also gives insight into the microstructure of brain tissue through diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging. Metabolic changes are also part of brain maturation and are assessed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Understanding and knowledge of the different steps in brain development are required to be able to detect morphologic and structural changes on neuroimaging. Consequently alterations in normal development can be depicted.

Keywords

brain; diffusion MRI; human development; MRI; MR spectroscopy

Introduction

From a single fertilized egg of about 0.14 mm in diameter, to an adult human being, the neurophysiology of development of the brain and nervous system is remarkable. Brain development is a dynamic phenomenon that can be imaged pre- and postnatally. Neuroimaging technique in the fetal period is mostly ultrasound, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is primarily performed after birth and in children. However fetal MRI indications, especially for evaluation of the nervous system, have increased during the past 10 years, particularly between 20 and 30 weeks of gestational age (GA). Because of improvement in neonatal intensive care, indications of brain MRI in neonates have also widely spread in the past 10 years. Moreover, MRI is also performed in highly premature neonates, rarely within the first 2 weeks for medical decision making, and more commonly at term-equivalent age to look for white-matter damage not suspected on ultrasonography.

From early development to midgestation, brain development is complex and includes gastrulation with formation of a trilaminar embryonic disc, induction of the neural plate, primary neurulation, segmentation and regionalization, and patterning of the neural tube with formation of the brain vesicles, of the commissures, histogenesis, and formation of the cortex. These steps are genetically programmed and some steps are interrelated. Increase in knowledge of genes involved in development did open the vast field of developmental biology, especially of brain malformations and tumors (Dellovade et al., 2006; Barkovich et al., 2012; Barkovich, 2013; Doherty et al., 2013).

This chapter will focus on the period from midgestation to childhood, the time at which MRI is performed in a clinical setting. Brain development and maturation include changes in morphology and in signal intensity on MRI that are related to the effects of brain composition changes on the MR signal during development.

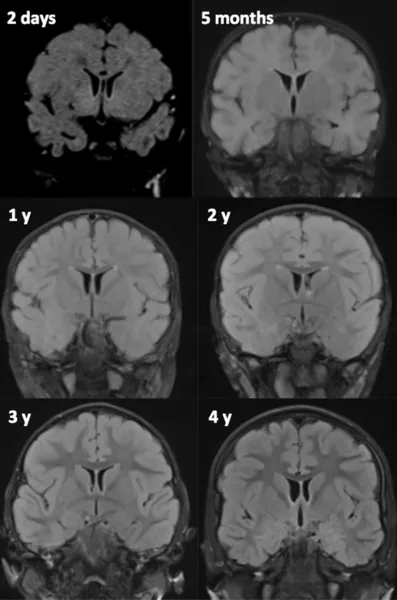

MRI Techniques

In neonates and young infants (Girard et al., 2007, 2012; Girard and Raybaud, 2011) the standard MRI protocol consists of axial and coronal T2-weighted images (WI), sagittal and axial gradient echo T1 WI, axial diffusion or diffusion tensor images, and proton spectroscopy. In older infants and children axial T2, coronal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and three-dimensional T1 WI are the common standard anatomic sequences. T1 WIs are generally acquired using gradient echo, spin echo, or inversion recovery (IR) images. GE and IR T1 WI allow excellent gray–white-matter differentiation, especially in young infants less than 6 months of age. Alternates for T1 WI consist of three-dimensional (3D) T1 images whenever possible. T2 WI can be acquired using spin echo, fast spin echo (FSE), or turbo spin echo (TSE) techniques. FSE and TSE images show myelin maturation at an earlier age than spin echo images due to increased magnetization transfer effects (Welker and Patton, 2012) and are obtained in a shorter acquisition time. Heavily T2-weighted sequences are used in infants less than 12 months of age to compensate for the long T1 values due to the increased cerebral water content (Girard et al., 1991). In older children a FLAIR sequence is also performed. Although FLAIR images are considered highly efficient in assessing the white matter, these images demonstrate a paradoxic signal pattern through infancy: in neonates the white matter is of low signal intensity as on T1 WI, then of high signal intensity in infants and young children, and reaches the mature aspect of low signal intensity as on T2 WI around 4 years of age (Fig. 57.1).

Proton spectroscopy pulse sequences can be acquired by monovoxel or multivoxel techniques. Position-resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence is commonly used, with short (30–35 ms) and long echo time (145 ms). Monovoxel techniques are preferred in both the pre and postnatal periods for spectroscopy in a clinical setting because chemical shift imaging (CSI), also named magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI), although able to give metabolic information from a slice or a volume with identification of spatial repartition of metabolites, is still technically difficult to acquire (especially because of contaminations), to process and interpret (especially because a spatial processing is necessary with the spectral processing), and is extremely sensitive to movement. Another disadvantage of CSI is that the experiment cannot be stopped (i.e., because of movement or clinical instability) because all the lines, columns, and slices of the CSI are needed to get spectra. Recently 3D CSI acquisitions with automatic postprocessing have been developed to improve reproducibility in the assessment of longitudinal follow-up of patients (Maudsley et al., 2010).

Diffusion images show the changing microstructure of the developing brain. Echoplanar diffusion images are routinely and easily performed in the neonate with an acquisition time of 1 minute to 1 minute 30 seconds. Sensitization gradients are applied following the three axes (x, y, z). Generated images consist of trace images and maps of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC). Diffusion images are also obtained by diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) with measurements made after diffusion gradients have been applied in multiple directions (at least six noncollinear). Acquisition time of this type of sequence is 3–4 minutes with six directions, 5–6 minutes with 12 directions and even longer with 20–64 directions provided the pixel size is isotropic and the slice thickness is thin. Shorter acquisition time can be obtained with nonisotropic pixels. The images generated include trace images, ADC map, fractional anisotropy (FA) map, color-coded orientation FA map, and map of longitudinal (axial) and radial diffusivity. DTI is particularly well adapted to the analysis of brain maturation, especially white matter, but also for the cortex. Indeed, DTI is a technique that samples the 3D water molecule displacement in vivo. DTI therefore provides supplementary, quantifiable information, in addition to ADC and trace images, about the anisotropy of water diffusion that reflects the 3D structural arrangement of brain tissue.

This technique also shows the white-matter parcellation assessed by tractography, which permits monitoring of FA, ADC in a specific tract. However, because of low FA in fetuses and neonates, postprocessing of the tractography tool is unlike the one used for the mature brain.

In utero brain MRI protocol (Brunel et al., 2004; Girard, 2005; Girard et al., 2009; Girard and Chaumoitre, 2012) includes T2 WI obtained in the three anatomic planes relative to the fetal head with ultrafast imaging such as half-Fourier single-shot turbo spin echo (HASTE) and True FISP images, at least one plane with T1 WI, diffusion WI in the axial plane by using the standard sequence with three b valu...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Handbook of Clinical Neurology 3rd Series

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributors

- Section 3: Spinal diseases

- Section 4: Diseases of the peripheral nervous system

- Section 5: Neurologic syndromes of the adult: when and how to image

- Section 6: Differential diagnosis of imaging findings

- Section 7: Pediatric neuroimaging

- Section 8: Interventional neuroimaging

- Section 9: Neuropathology

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Neuroimaging, Part II by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Neurology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.