![]()

Chapter 1. Introduction

1. SOME GENERAL REMARKS ABOUT CANCER AND CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY

Cancer is a collective term used for a group of diseases that are characterized by the loss of control of the growth, division, and spread of a group of cells, leading to a primary tumor that invades and destroys adjacent tissues. It may also spread to other regions of the body through a process known as metastasis, which is the cause of 90% of cancer deaths. Cancer remains one of the most difficult diseases to treat and is responsible for about 13% of all deaths worldwide, and this incidence is increasing due to the ageing of population in most countries, but specially in the developed ones.

Cancer is normally caused by abnormalities of the genetic material of the affected cells. Tumorigenesis is a multistep process that involves the accumulation of successive mutations in oncogenes and suppressor genes that deregulates the cell cycle. Tumorigenic events include small-scale changes in DNA sequences, such as point mutations; larger-scale chromosomal aberrations, such as translocations, deletions, and amplifications; and changes that affect the chromatin structure and are associated with dysfunctional epigenetic control, such as aberrant methylation of DNA or acetylation of histones.[1] About 2,000–3,000 proteins may have a potential role in the regulation of gene transcription and in the complex signal-transduction cascades that regulate the activity of these regulators. Cancer is not only a cell disease, but also a tisular disease in which the normal relationships between epithelial cells and their underlying stromal cells are altered.[2]

Cancer therapy is based on surgery and radiotherapy, which are, when possible, rather successful regional interventions, and on systemic chemotherapy. Approximately half of cancer patients are not cured by these treatments and may obtain only a prolonged survival or no benefit at all. The aim of most cancer chemotherapeutic drugs currently in clinical use is to kill malignant tumor cells by inhibiting some of the mechanisms implied in cellular division. Accordingly, the antitumor compounds developed through this approach are cytostatic or cytotoxic. However, the knowledge of tumor biology has exploded during the past decades and this may pave the way for more active, targeted anticancer drugs.[3] The introduction of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib as a highly effective drug in chronic myeloid lekemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumors[4] was a proof of the concept of effective drug development based on the knowledge of tumor biology.[5]

Effective targeted therapies may be suitable only for small subgroups of patients.[6] Pharmacogenetics, which focuses on intersubject variation in therapeutic drug effects and toxicity depending of polymorphisms, is particularly interesting in oncology since anticancer drugs usually have a narrow margin of safety. The dose of chemotherapeutic agents is generally adjusted by body surface area, but this parameter is not sufficient to overcome differences in drug disposition.[7] DNA microarray technology permits to study alterations in the transcriptional level of entire genomes, and may become an important tool for predicting the chemosensitivity of tumors before treatment.

It is obvious that cancer chemotherapy is a very difficult task.[8] One of its main associated problems is the nonspecific toxicity of most anticancer drugs due to their biodistribution throughout the body, which requires the administration of a large total dose to achieve high local concentrations in a tumor. Drug targeting aims at preferred drug accumulation in the target cells independently on the method and route of drug administration.[9] One approach that allows to improve the selectivity of cytotoxic compounds is the use of prodrugs that are selectively activated in tumor tissues, taking advantage of some unique aspects of tumor physiology, such as selective enzyme expression, hypoxia, and low extracellular pH. More sophisticated tumor-specific delivery techniques allow the selective activation of prodrugs by exogenous enzymes (gene-directed and antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy). Furthermore, the increased permeability of vascular endothelium in tumors (enhanced permeability and retention, EPR effect) permits that nanoparticles loaded with an antitumor drug can extravasate and accumulate inside the interstitial space, where the drug can be released as a result of normal carrier degradation (see also Section 4).[10]

Another problem in cancer chemotherapy is drug resistance. After the development of a resistance mechanism in response to a single drug, cells can display cross-resistance to other structural and mechanistically unrelated drugs, a phenomenon known as multidrug resistance (MDR) in which ATP-dependent transporters have a significant role.[11]

Finally, a major problem in the development of anticancer drugs is the large gap from promising findings in preclinical in vitro and in vivo models to the results of clinical trials. The problems found in this transition arise because experimental cancer models greatly differ from patients, who very often suffer from a much more complex therapeutic situation. Although a large number of clinical trials are in progress and new results are continuously being published, the real clinical efficacy of most of these treatments is usually disappointing and a statistically significant benefit is observed for very few of them.[12] It has been claimed that development and utilization of more clinically relevant cancer models would represent a major advance for anticancer drug research.

2. A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ROLE OF CHEMISTRY IN CANCER CHEMOTHERAPY

Chemistry has had varying roles in the discovery and development of anticancer drugs since the beginning of cancer therapies.[13] In its early history, chemical modification of sulfur mustard gas led to the serendipitous discovery of the still clinically useful nitrogen mustards. Since those years, synthetic chemistry has been extensively used to modify drug leads, especially those of natural origin, and to solve the problem of the often scarce supply of natural products by developing semisynthetic or synthetic strategies (see Section 3).

Since the 1950s, chemistry has also generated many antitumor drug leads through in vitro screening programs promoted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in the United States by using a range of cancer cell lines. In this early period, transplantable rodent tumors models characterized by a high growth rate were used for in vivo screening. Later on, human tumor xenografts, based on transplantation of human tumor tissue into immune-tolerant animals, became also important tools for selecting antitumor drugs because the xenograft models allowed to simulate a chemotherapeutic effect under conditions closer to man. In the late seventies and early eighties, the role of chemotherapy was extended to preoperative and postoperative adjuvants, radiosensitizers to enhance radiation effects, and supportive therapy to increase the tolerance of the organism toward toxicity.[14]

The rationale for the use of conventional cytotoxic antitumor drugs is based on the theory that rapidly proliferating and dividing cells are more sensitive to these compounds than the normal cells.[15] The interactions of cytotoxic agents with DNA are now better defined, and new compounds that target particular base sequences may inhibit transcription factors in a more specific manner. DNA can be considered as a true molecular receptor that is capable of molecular recognition and of triggering response elements which transmit signals through protein interactions.[16] The binding properties of DNA ligands can be rationalized on the basis of their structural and electronic complementarity with the functional groups present in the major and minor grooves of particular DNA sequences which are mainly recognized by specific hydrogen bonds.[17]

Although DNA continues to be an essential target for anticancer chemotherapy, much recent effort has been directed to discover antitumor drugs specifically suited to target molecular aberrations which are specific to tumor cells.[18] This new generation of antitumor agents is based on research in areas such as cell signaling processes, angiogenesis and metastasis, and inhibition of enzymes that, like telomerase, are reactivated in the majority of cancer cells.[19] These goals may use small molecule drugs or other macromolecular structures, such as monoclonal antibodies that bind to antigens present preferentially or exclusively on tumor cells. The aim of other research programs is to develop compounds that interfere with gene expression to suppress the production of damaged proteins involved in carcinogenesis. In the antisense approach, the mRNA translation is interfered thereby inhibiting the translation of the information at the ribosome, while in the antigene therapy, a direct binding to the DNA double strand inhibits transcription.[20]

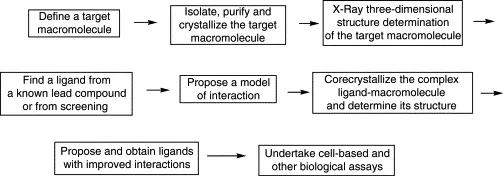

The knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of these new target macromolecules, which are normally proteins, by using X-ray crystallography, permits the rational design of small molecules that mimic the stereochemical features of the macromolecule functional domains. The principal steps in structure-based drug design using X-ray techniques are summarized in Fig. 1.1. In the absence of a three-dimensional structure of a target protein, homology criteria may be applied using the experimental structure of similar proteins, which is especially useful in the case of individual subfamilies. The knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of a target also permits to design and generate virtual libraries of potential drug molecules to be used for in silico screening.

Figure 1.1. Main steps in X-ray-guided drug design.

Progress in the development of potential drug molecules is often problematic because it is difficult to convert them into “druggable” compounds, that is, into molecules with adequate pharmaceutical properties. To this end, it is absolutely necessary to know the chemical properties of a lead compound, especially solubility and reactivity, because these properties are relevant for cellular uptake and metabolism in order to transform this lead compound into a real drug. The “druggability” of a drug candidate describes their adequate absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion ...