Introduction

Student feedback on aspects of their experience is ubiquitous. Indeed, it is now expected. The recent Parliamentary Select Committee report in the UK (House of Commons, 2009) concluded, inter alia, with the following student comment: ‘What contributes to a successful university experience is an institution which actively seeks, values and acts on student feedback’ (p. 131).

Carr et al. (2005) commented:

Student surveys are perhaps one of the most widely used methods of evaluating learning outcomes (Leckey and Neill, 2001: 24) and teaching quality. Students may have a certain bias which influences their responses, however, the student perspective is advantageous for being much more immediate than analyses of, for example, completion and retention rates. Further, the view presented in the survey is that of the learner, ‘the person participating in the learning process’ (Harvey, 2001). Harvey also identified the value in the richness of information that can be obtained through the use of student surveys (Harvey, 2001).

Much earlier, Astin (1982), for example, had argued that students are in a particularly good position to comment upon programmes of study and thus to assist institutions to improve their contribution to student development. Hill (1995) later argued, from a student perspective, that students are ‘often more acutely aware of problems, and aware more quickly’ than staff or visiting teams of peers; which is, ‘perhaps, the primary reason for student feedback on their higher education to be gathered and used regularly’ (p. 73).

However, this has not always been the case. Twenty years ago, systematic feedback from students about their experience in higher education was a rarity. With the expansion of the university sector, the concerns with quality and the growing ‘consumerism’ of higher education, there has been a significant growth of, and sophistication in, processes designed to collect views from students.

Most higher education institutions, around the world, collect some type of feedback from students about their experience of higher education. ‘Feedback’ in this sense refers to the expressed opinions of students about the service they receive as students. This may include: perceptions about the learning and teaching; the learning support facilities, such as libraries and computing facilities; the learning environment, such as lecture rooms, laboratories, social space and university buildings; support facilities including refectories, student accommodation, sport and health facilities and student services; and external aspects of being a student, such as finance, car parking and the transport infrastructure.

Student views are usually collected in the form of ‘satisfaction’ feedback in one way or another; albeit some surveys pretend that by asking ‘agree-disagree’ questions they are not actually asking about satisfaction with provision. Sometimes, but all too rarely, there are specific attempts to

obtain student views on how to improve specific aspects of provision or on their views about potential or intended future developments.

The reaction to student views also seems to have shifted. Baxter (1991) found that over half the respondents in a project he reported experienced improved job satisfaction and morale and almost all were influenced by student evaluation to change their teaching practice. Massy and French (2001) also stated, in their review of the teaching quality in Hong Kong, that ‘staff value and act upon student feedback’ and are ‘proactive in efforts to consult with students’ (p. 38). However, more recently, Douglas and Douglas (2006) suggested that staff have very little faith in student feedback questionnaires, whether module or institutional. This is not so surprising when student feedback processes tend to be bureaucratised and disconnected from the everyday practice of students and teaching staff; a problem that is further compounded by a lack of real credit and reward for good teaching.

Ironically, although feedback from students is assiduously collected in many institutions, it is less clear that it is used to its full potential. Indeed, a question mark hangs over the value and usefulness of feedback from students as collected in most institutions. The more data institutions seek to collect, the more cynical students seem to become and the less valid the information generated and the less the student view is taken seriously. Church (2008) remarked that ‘students can often feel ambivalent about completing yet another course or module questionnaire. This issue becomes particularly acute when students are not convinced of the value of such activity –- particularly if they don’t know what resulted from it.’

In principle, feedback from students has two main functions: internal information to guide improvement; and external information for potential students and other stakeholders. In addition, student feedback data can be used for control and accountability purposes when it is part of external quality assurance processes. This is not discussed here as it is in fact a trivial use of important data, which has as its first priority improvement of the learning experience.

Improvement

It is not always clear how views collected from students fit into institutional quality improvement policies and processes. To be effective in quality improvement, data collected from surveys and peer reviews must be transformed into information that can be used within an institution to effect change.

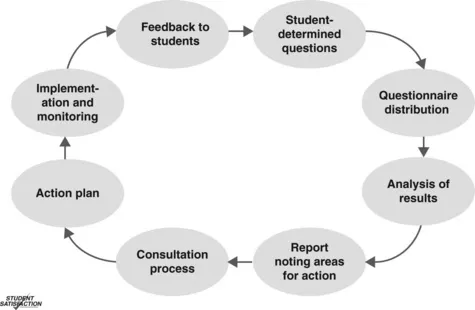

To make an effective contribution to internal improvement processes, views of students need to be integrated into a regular and continuous cycle of analysis, reporting, action and feedback, be it at the level of an individual taught unit or at the institutional level (Figure 1.1). In many cases it is not always clear that there is a means to close the loop between data collection and effective action, let alone feedback to students on action taken, even within the context of module feedback questionnaires. Closing the loop is, as various commentators have suggested, an important, albeit neglected, element in the student feedback process (Ballantyne, 1997; Powney and Hall, 1998; Watson, 2003; Palermo, 2004; Walker-Garvin, undated). Watson (2003) argued that closing the loop and providing information on action taken encourages participation in further research and increases confidence in results, as well as it being ethical to debrief respondents. It also encourages the university management to explain how they will deal with the highlighted issues.

Figure 1.1 Satisfaction cycle

Making effective use of feedback requires that the institution has in place an appropriate system at each level that:

identifies and delegates responsibility for action;

encourages ownership of plans of action;

requires accountability for action taken or not taken;

communicates back to students on what has happened as a result of their feedback (closes the loop);

commits appropriate resources.

As Yorke (1995) noted, ‘The University of Central England has for some years been to the fore in systematising the collection and analysis of data in such a way as to suggest where action might be most profitably directed (Mazelan et al., 1992)’ (p. 20). However, establishing an effective system is not an easy task, which is why so much data on student views is not used to effect change, irrespective of the good intent...