- 704 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Sturkie's Avian Physiology

About this book

Sturkie's Avian Physiology is the classic comprehensive single volume on the physiology of domestic as well as wild birds. The Fifth Edition is thoroughly revised and updated, and includes new chapters on the physiology of incubation and growth. Chapters on the nervous system and sensory organs have been greatly expanded due to the many recent advances in the field. The text also covers the physiology of flight, reproduction in both male and female birds, and the immunophysiology of birds.The Fifth Edition, like the earlier editions, is a must for anyone interested in comparative physiology, poultry science, veterinary medicine, and related fields. This volume establishes the standard for those who need the latest and best information on the physiology of birds.- Thoroughly updated and revised- Coverage of both domestic and wild birds- New larger format- Only comprehensive, single volume devoted to birds

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

I INTRODUCTION

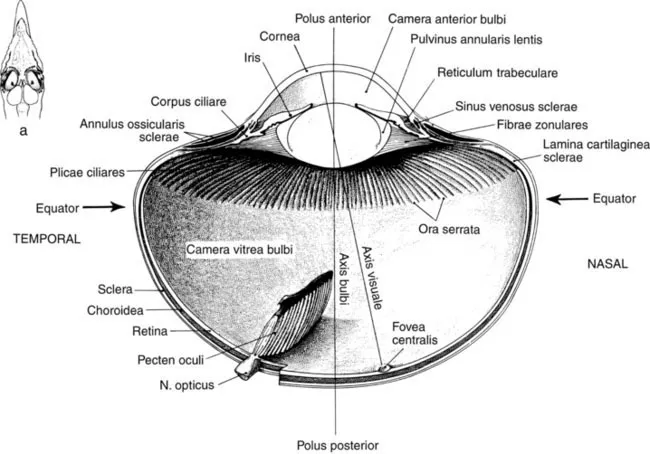

II STRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONS OF THE EYE

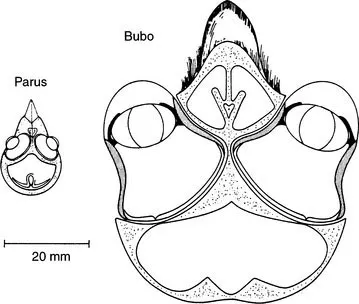

A Eye Shape, Stereopsis, and Acuity

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface to the Fifth Edition

- Chapter 1: Sensory Physiology: Vision

- Chapter 2: The Avian Ear and Hearing

- Chapter 3: The Chemical Senses in Birds

- Chapter 4: The Somatosensory System

- Chapter 5: Functional Organization of the Spinal Cord

- Chapter 6: Motor Control System

- Chapter 7: The Autonomic Nervous System of Avian Species

- Chapter 8: Skeletal Muscle

- Chapter 9: The Cardiovascular System

- Chapter 10: Respiration

- Chapter 11: Renal and Extrarenal Regulation of Body Fluid Composition

- Chapter 12: Gastrointestinal Anatomy and Physiology

- Chapter 13: Energy Balance

- Chapter 14: Regulation of Body Temperature

- Chapter 15: Flight

- Chapter 16: Introduction to Endocrinology: Pituitary Gland

- Chapter 17: Thyroids

- Chapter 18: The Parathyroids, Calcitonin, and Vitamin D

- Chapter 19: Adrenals

- Chapter 20: Pancreas

- Chapter 21: The Pineal Gland, Circadian Rhythms, and Photoperiodism

- Chapter 22: Reproduction in the Female

- Chapter 23: Reproduction in Male Birds

- Chapter 24: Incubation Physiology

- Chapter 25: Physiology of Growth and Development

- Chapter 26: Immunophysiology

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app