Because each of these principles has a meaningful application within a security organization, it is helpful to elaborate on them.

Logical Division of Work

The necessity for the division of work becomes apparent as soon as you have more than one person on the job. How the work is divided can have a significant impact on the results at the end of the day. The manner and extent of the division of work influence the product or performance qualitatively as well as quantitatively. The logical division of work, therefore, deserves close attention.

There are five primary ways in which work can be divided:

Purpose

It is most common for work to be divided according to purpose. The Security Department could be organized into two divisions: a Loss Control or Loss Prevention division (its purpose is to prevent losses) and a Detection division (its purpose is to apprehend those who defeated the efforts of the prevention unit).

Process or Method

A process unit is organized according to the method of work; all similar processes are in the same unit. An example in security might be the alarm room operators and dispatchers or the credit card investigators unit of the general investigative section.

Clientele

Work may also be divided according to the clientele served or worked with. Examples here would be the background screening personnel, who deal only with prospective and new employees; store detectives, who concentrate on shoplifters; or general retail investigators, who become involved with dishonest employees, forgers, and other criminal offenders.

Division of work by purpose, process, or clientele is really a division based on the nature of the work and consequently is referred to as “functional.” In other words, the grouping of security personnel to perform work divided by its nature (purpose, process, or clientele) is called functional organization.

For many organizations, the functional organization constitutes the full division of work. Security, however, like police and fire services in the public sector, usually has around-the-clock protective responsibilities. In addition, unlike its cousins in the public sector, it may have protective responsibilities spread over a wide geographic area.

Time

At first glance, the 24-hour coverage of a given facility may appear relatively simple. It might be natural to assume there should be three, 8-hour shifts with fixed posts, patrol, and the communication and alarm center all changing at midnight, 8:00 a.m

., and

4:00 p.m

. However, a number of interesting problems surface when a department begins organizing by time:

• How many security people are necessary on the first shift? If a minimum security staff takes over at midnight and the facility commences its business day at 7:00 a.m., can you operate for 1 hour with the minimum staff or must you increase coverage prior to 7:00 a.m. and overlap shifts? (There are hundreds of variables to just this type of problem.)

• If you have two or more functional units, with some personnel assigned to patrol and others assigned to the communications and alarm center (in another organizational pyramid altogether), who is in command at 3:00 a.m.? The question of staff supervision confuses many people. (See Chapter 5 for a detailed discussion of staff supervision.)

• How much supervision is necessary during facility downtime? If the question is not how much, then how is any supervision exercised at 3:00 a.m.?

• If there are five posts, each critical and necessary, and five persons are scheduled and one fails to show, how do you handle the situation? Should you schedule six persons for just that contingency?

These and other problems do arise and are resolved regularly in facilities of every kind. Organizing by time, a way of life for security operations, does create special problems that demand consideration, especially if this approach to the division of work is a new undertaking for a company.

Geography

Whenever a Security Department is obliged to serve a location removed from the headquarters facility, and one or more security personnel are assigned to the outlying location, there is one major issue that must be resolved: To whom does the security personnel report — to security management back at headquarters or to site management (which is nonsecurity)?

The real issue is should nonsecurity management have direct supervision over a security employee who has technical or semitechnical skills that are beyond the competence or understanding of nonsecurity management personnel?

In defining the type of authority an executive or supervisor exercises, a distinction is generally made between line and staff authority. Although these terms have many meanings, in its primary sense, line authority implies a direct (or single line) relationship between a supervisor and his or her subordinate; the staff function is service or advisory in nature.

Security personnel should only be directly supervised by security management. Site management may provide staff supervision, providing suggestions and assistance, but these should be restricted to such matters as attention to duty, promptness in reporting, and compliance with general rules. Detailed security activities fall outside the jurisdiction of site management.

Nonsecurity management should not have line authority (direct supervision) over security, not only because of the issue of professional competency but also because site management should not be beyond the “reach” of security. Site management would indeed be out of reach if the only internal control, security, was subject to its command. Site management would be free to engage in any form of mischief, malpractice, or dishonesty without fear of security’s reporting the activities to company headquarters.

Clear Lines of Authority and Responsibility

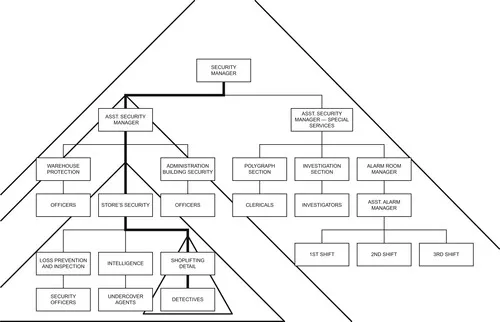

Once the work has been properly divided, the organization takes on the appearance of a pyramid-like structure, within which are smaller pyramids, as illustrated in Figure 1–1. Each part of each pyramid defines, with exactness, a function or responsibility and to whom that function is responsible. One can easily trace the solid line upward to the Security Manager or Security Director who is ultimately responsible for every function within the security organization.

Not only is it important to have this organizational pyramid documented, normally in the form of an organizational chart, it is also essential that security employees have access to the chart so they can see exactly where they fit into the organization pattern, to whom they are responsible, to whom their supervisor is responsible, and so on right up to the top. Failure to so inform employees causes unnecessary confusion, and confusion is a major contributor to ineffective job performance.

In addition, the organizational chart is a subtle motivator. People can see themselves moving up in the boxes; for goal-setting to be successful, one must be able to envision oneself already in possession of one’s goal.

Finally, the apparent rigidity of boxes and lines in the organizational chart must not freeze communication. Employees at the lowest layer of the pyramid must feel free to communicate directly with the Security Manager without obtaining permission from all of the intervening levels of supervision.