![]()

Chapter S. Scrimshaw

Scrimshaw is an occupational handicraft of mariners employing by-products of the whale fishery, often in combination with other found materials. Indigenous to the whaling industry, where it was typically a pursuit of leisure time at sea, it was also adopted in other trades and was occasionally practiced ashore (Flayderman, 1972). It arose among Pacific Ocean whalers circa 1817–1824, persisted throughout the classic “hand-whaling” era of sailing-ship days into the twentieth century, and persisted in degraded form among “modern” whalers on factory ships and shore stations until the industry shut down in the third quarter of the twentieth century (Basseches et al., 1991). Since the early twentieth century, similar materials and techniques have simultaneously been employed by non-mariner artisans for both commercial and hobbyist purposes.

There is no consensus regarding etymology. Plausible and eccentric theories alike have been advanced without any creditable evidentiary basis, whereas academic lexicography (notoriously inconclusive respecting nautical terms) fails to present any convincing hypothesis. The term—also rendered skrimshank, skimshander, skirmshander, and skrimshonting—first appeared in American shipboard usage circa 1826, when the recreational practice of scrimshaw was less than a decade progressed. It originally referred not to whalers’ private diversions, but to the fairly common practice whereby crewmen were required to make articles for ship's work (such as tools, tool handles, thole pins, belaying pins, and tackle falls). Sperm whale BONE is ideally suited to such uses: on any “greasy luck” voyage it was in plentiful supply at no cost, its workability is equivalent to the best cabinetmaking hardwoods, its tensile strength is greater than oak, and for many applications its self-lubricating properties were highly desirable. Such was analogously the case regarding the adaptability of cetacean bone and ivory to whales’ recreational handicrafts, to which the term “scrimshaw” (and its many variants) came to refer by the 1830s.

I. Materials and Species

Materials associated most commonly with scrimshaw are the ivory teeth and skeletal bone of the SPERM WHALE (Physeter macrocephalus), the ivory tusks of the WALRUS (Odobenus rosmarus), and the BALEEN of various mysticete species (the toothless, baleen-bearing whales). In the nineteen century the principal prey species were, roughly in descending order of importance, sperm whale, right whales (Eubalaena spp.), Arctic bowhead (Balaena mysticetus), gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus), and humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae). These and the long-finned pilot whale or so-called “blackfish” (Globicephala melas), which was hunted primarily from shore, were taken primarily for oil, the mysticetes secondarily for baleen. [The fast-swimming blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) could not be hunted effectively prior to the introduction of steam propulsion and heavy-caliber harpoon cannons in the late nineteenth century.] From the late sixteenth century, by reason of geographical proximity of Arctic habitats and similar uses of their meat and oil, the hunt for walruses was intimately conjoined with commercial whaling. Later, even when whalers were no longer taking walruses themselves, they characteristically obtained walrus tusks through barter with indigenous Northern peoples.

Commercial uses of walrus ivory were few; there was no significant commercial application for cetacean skeletal bone until the twentieth century (when it was ground and desiccated into industrial-grade meal and fertilizer). The utility and market value of baleen (“whalebone”) were subject to mercurial fluctuations of fashion, and sperm whale teeth had little or no commodity value. They thus became available for whalers’ recreational use, as did teeth of the Antarctic elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), the lower mandibles of various dolphins and porpoises, and tusks of the elusive NARWHAL (Monodon monoceros). (Narwhal ivory proved too difficult and brittle for anything much beyond canes and analogous shafts, such as hatracks or bedposts.)

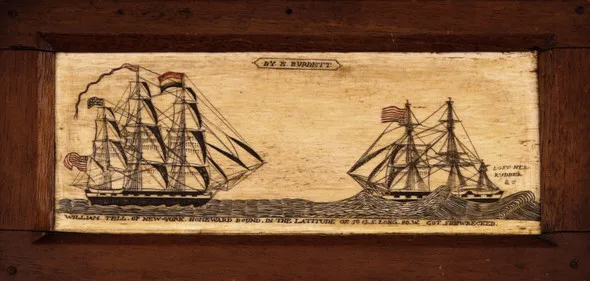

The characteristic pigment for highlighting engraved scrimshaw was lampblack, which is essentially a viscous suspension of carbon particles in oil. (The notion that sailors used tobacco juice for this is a colorful fabrication with no basis in fact.) Lampblack, collected easily from lamps, stoves, and tryworks (shipboard oil-rendering apparatus), was in abundant supply on a whale ship. Colors were introduced almost at the outset: Edward Burdett was using sealing wax and other pigments by 1827 (Fig. 1); full polychrome scrimshaw debuted within the next decade. Sealing wax had the advantages of being universally available, relatively inexpensive, brilliantly colored, and colorfast. Applied properly, it has proven resilient and tenacious, the color as vivid today as when the scrimshaw was new. Improper application—if the cuts are too smooth or insufficiently contoured to grab and hold the wax—results in significant losses from handling and natural desiccation. Sealing wax had the disadvantage of offering only a limited spectrum of colors, all strong. Ambient pigments, however, could be mixed and blended, affording greater subtlety. From the characteristic leeching of pigment into the substrata of some polychrome scrimshaw, a phenomenon that occurs with water- and alcohol-soluble colors but not with waxes or heavy oil-based pigments, it is clear that ambient colors were also favored. Store-bought inks, homemade dyes extracted from berries, and greens from common verdigris seem to predominate; however, their composition has not been investigated comprehensively.

Figure 1. Pan bone plaque by Edward Burdett (1805–1833) of Nantucket, circa 1828. The earliest known scrimshaw artist, Burdett was active from 1824 until he was killed by a whale in 1833. His work is characterized by a bold, confident style, with deep blacks and red sealing-wax highlights. He was serving as a mate in the William Tell when he engraved this section of sperm whale bone, inscribed “William Tell. of New York. homeward bound. in the latitude of. 50 13. S. long[itude] 80. W. got shipwrecked”; “lost her rudder & c.”; “by. E. Burdett.” 15.7×31.8 cm. Kendall Collection, New Bedford Whaling Museum.

Inlay and other secondary materials—rare on engraved scrimshaw but often encountered on “built” or “architectonic” scrimshaw—were typically obtained at little or no cost, such as other marine byproducts (tortoise shell, mother-of-pearl, sea shells), various woods brought from home or obtained in various ports of call (including exotic tropical species from Africa and Polynesia), and miscellaneous bits of metal (fastenings and finials were often crafted from silver- or copper-alloy coins, typically coins minted in Mexico and South America).

II. Scrimshaw Precursors

Medieval European artistic productions in walrus ivory and cetacean bone were many, but the whalers themselves had no part in them beyond gathering the raw materials. Cetacean bone panels and stilettos survive from the Viking era, some incised with rope patterns and animal figures, and cetacean bones served as beams in vernacular buildings in Norway and the Friesian Islands, but even these do not appear to have been made by whalers and are not known to have been part of their occupational culture. Monastic artisans in Denmark and East Anglia carved walrus ivory and cetacean bone into votive art, primarily altar pieces, friezes, and crosses, whereas craftsmen at Cologne and elsewhere produced secular game pieces and chessmen from the same materials. So important was the “Royal Fish” to the Viking economy that a highly sophisticated body of law evolved to regulate whaling itself and the ownership, taxation, distribution, and export of whale products, whether acquired fortuitously (from stranded carcasses) or by hunting. Pliny the Elder (first century C.E.), Olaus Magnus (1555), Conrad von Gessner (1558), and Ambroise Pare (1582) listed the uses of baleen for whips, springs, garment stays, and umbrella ribs; the emergence of pelagic Arctic whaling in the seventeenth century enco...