1 INTRODUCTION

Suppose that several or even infinitely many theories are compatible with the information available. How ought one to choose among them, if at all? The traditional and intuitive answer is to choose the “simplest” and to cite Ockham’s razor by way of justification. Simplicity, in turn, has something to do with minimization of entities, description length, causes, free parameters, independent principlies, or ad hoc hypotheses, or maximization of unity, uniformity, symmetry, testability, or explanatory power.

Insofar as Ockham’s razor is widely regarded as a rule of scientific inference, it should help one to select the true theory from among the alternatives. The trouble is that it is far from clear how a fixed bias toward simplicity could do so [Morrison, 2000]. One wishes that simplicity could somehow indicate or inform one of the true theory, the way a compass needle indicates or informs one about direction. But since Ockham’s razor always points toward simplicity, it is more like a compass needle that is frozen into a fixed position, which cannot be said to to indicate anything. Nor does it suffice to respond that a prior bias toward simplicity can be corrected, eventually, to allow for convergence to the truth, for alternative biases are also correctable in the limit.

This paper reviews some standard accounts of Ockham’s razor and concludes that not one of them explains successfully how Ockham’s razor helps one find the true theory any better than alternative empirical methods. Thereafter, a new explanation is presented, according to which Ockham’s razor does not indicate or inform one of the truth like a compass but, nonetheless, keeps one on the straightest possible route to the true theory, which is the best that any inductive strategy could possibly guarantee. Indeed, no non-Ockham strategy can be said to guarantee so straight a path. Hence, a truth-seeker always has a good reason to stick with Ockham’s razor even though simplicity does not indicate or inform one of the truth in the short run.

2 STANDARD ACCOUNTS

The point of the following review of standard explanations of Ockham’s razor is just to underscore the fact that they do not connect simplicity with selecting the true theory. For the most part, the authors of the accounts fairly and explicitly specify motives other than finding the true theory — e.g., coherence, data-compression, or accurate estimation. But the official admonitions are all too easily forgotten in favor of a vague and hopeful impression that simplicity is a magical oracle that somehow extends or amplifies the information provided by the data. None of the following accounts warrants such a conclusion, even though several of them invoke the term “information” in one way or another.

2.1 Simple Virtues

Simple theories have attractive aesthetic and methodological virtues. Aesthetically, they are more unified, uniform and symmetrical and are less ad hoc or messy. Methodologically, they are more severely testable [Popper, 1968; Glymour, 1981; Friedman, 1983; Mayo, 1996], explain better [Kitcher, 1981], predict better [Forster and Sober, 1994], and provide a compact summary of the data [Li and Vitanyi, 1997; Rissanen, 1983].1 However, if the truth happens not to be simple, then the truth does not possess the consequent virtues, either. To infer that the truth is simple because simple worlds and the theories that describe them have desirable properties is just wishful thinking, unless some further argument is given that connects these other properties with finding the true theory [van Fraassen, 1981].

2.2 Bayesian Prior Probabilities

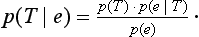

According to Bayesian methodology, one should update one’s degree of belief P(T) in theory T in light of evidence e according to the rule:

Subjective Bayesians countenance any value whatever for the prior probability p(T), so it is permissible to start with a prior probability distribution biased toward simple theories [Jeffreys, 1985]. But the mere adoption of such a bias hardly explains how finding the truth is facilitated better by that bias than by any other.

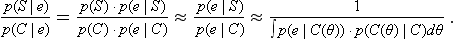

A more subtle Bayesian argument seems to avoid the preceding circle. Suppose that S is a simple theory that explains observation e, so that p(e|S) ≈ 1 and that C =∃θC(θ) is a competing theory that is deemed more complex due to its free parameter θ, which can be tuned to a small range of “miraculous” values over which p(e|C(θ)) ≈ 1. Strive, this time, to avoid any prior bias for or against simplicity. Ignorance between S and C implies that p(S) ≈ p(C). Hence, by the standard, Bayesian calculation:

Further ignorance about the true value of θ given that C is true implies that p(C(θ)|C) is flattish. Since p(e|C(θ)) is high only over a very small range of possible values of θ and p(C(θ)|C) is flattish, the integral assumes a value near zero. So the posterior probability of the simple theory S is sharply greater than that of C [Rosenkrantz, 1983]. It seems, therefore, that simplicity is “truth conducive”, starting from complete ignorance.

The magic evaporates when the focus shifts from theories to ways in which the alternative theories can be true. The S world carries prior probability 1/2, whereas the prior probability of the range...