Jan Willem Erismana, Tom Brydgesb, Keith Bullc, Ellis Cowlingd, Peringe Grennfelte, Lars Nordbergf, Kenichi Satakeg, Tony Schneiderh, Stan Smeuldersi, Klaas W. Van der Hoekj, Jan R. Wisniewskik and Joe Wisniewskik, aECN, P.O. Box 1, 1755 ZG Petten, The Netherlands; bEnvironment Canada, P.O. Box 5050, Burlington, Ontario L7R 4A6, Canada; cInstitute of Terrestrial Ecology, Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon PE17 2LS, UK; dNorth Carolina State University, P.O. Box 8002, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA; eSwedish Environmental Research Institute, P.O. Box 47086, S-402 58 Göteborg, Sweden; fUN-ECE, Environment and Human Settlements Division, Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva, Switzerland; gNational Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, 305 Ibaraki, Japan; hSoest, The Netherlands; iMinistery of Environment, P.O Box 30945, The Hague, Tthe Netherlands; jRIVM, P.O. Box 1, 3720 BA Bilthoven, The Netherlands; kWisniewski & Associates, Inc., P.O. Box 1409, 22101 Virginia, USA

1 Introduction

The history of human exploitation of the earth’s natural resources began as the history of a hungry animal in search of food. Simple clothing and primitive shelter were the first amenities of life. The need for stable supplies of food led at first to domestication of cereals, the herding of livestock and poultry and eventually to the agricultural revolution.

Wood and stone implements were the first tools to be used for fashioning primitive furniture and rafts or boats. Wood was the first material used for constructing shelter, as fuel for warming habitations, and later for smelting metals. Wind and falling water were the first sources of energy for transport in ships and for grinding grain into flour. Irrigation increased the yield of crops. Human and agricultural wastes were used for fertilising cropland. Later, disposal of both types of waste became a serious problem in heavily populated areas and this was solved by spreading too much waste over the land, dumping it in rivers or oceans, and burning or burying it, thereby fouling the air and water.

The use of fossil fuels, the discovery of electricity, the invention of the steam engine, the development of railroads and the internal combustion engine, and the invention of the automobile, all became part of the industrial revolution. The discovery of modern concepts of plant and animal nutrition led to the worldwide use of synthetic fertilisers and widespread planting of legumes that fix atmospheric nitrogen. Cheap and convenient transport expanded the space scales and decreased the time scales of human impacts on natural resources and environment all over the world.

As human populations and the individual and collective appetites of people for material things and the amenities of modern life have increased, so also has concern about disparities in wealth, and the sustainability of modern agriculture and industrial development. The natural cycling and exchange of carbon, sulphur, and nitrogen among the various compartments of the earth including the air, soils, standing stock of biomass (mostly forest trees), and the streams, rivers, estuaries, and oceans of the earth have been drastically perturbed by human activities of many sorts on every continent.

Human perturbations of the carbon cycle of the earth has led to concern about global climate change. Sulphur pollution of the air has led to a new understanding of the global sulphur cycle including the release of sulphur by smelting of metals and burning of fossil fuels, its dispersal in air, its toxicity to humans and its acidifying effects on ecosystems.

Recently, society has also begun to recognise that nitrogen too plays not only a central role in plant and animal agriculture and forest production, but also an equally central role in air and water pollution problems — including ozone and particulate matter pollution; acidification and eutrophication of ecosystems, lakes, streams, estuaries, near-coastal oceans and terrestrial ecosystems; contamination of surface and groundwater supplies of drinking water, changing the biodiversity of landscapes; destruction of the ozone layer, global climate change and reduction in visibility. One nitrogen containing molecule can have a cascade of effects: for example, first it contributes to urban smog or direct effects on vegetation, then it contributes to acidification/eutrophication and/ or pollution of surface water, groundwater and/or coastal water, and finally it contributes to the greenhouse effect through emission of N2O. These facts, and the uncertainties associated with these facts, all emphasise the need for a more complete scientific understanding of both the beneficial and detrimental effects and the intended and unintended consequences of continuously increasing circulation of nitrogen in the commerce and in the atmosphere and biosphere of the earth.

So far, abatement strategies have been focused on individual themes, such as acidification, eutrophication, ozone layer destruction, global warming, etc. It may be more effective to couple and adjust abatement strategies resulting in a reduction of more than one effect. The First International Nitrogen Conference was organised by the Netherlands’ Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM), the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) and the Netherlands Energy Research Foundation (ECN) in order to review current knowledge and to stimulate discussion and collaboration between experts in the fields of agriculture and forest production and nitrogen pollution, policy makers and target groups.

The conference was held under the auspices of the Executive Body for the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN/ECE) and took place from 23 to 27 March 1998 in Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands. The conference was attended by 200 people representing 30 countries from all over the world. The objectives of the Nitrogen Confer-N-s was to provide a forum for discussion and debate about:

1. the present state of scientific understanding of the nitrogen cycle of the earth at global, regional, and local scales, and

2. the adequacy of contemporary tools for management of nitrogen both as a nutrient input into agriculture and forestry and as a cause of air, water, and soil pollution.

This paper provides the main conclusions and recommendations of the conference. Section 2 gives some background information and Section 3 lists the actual conference statements in the form of conclusions and recommendations.

2 General background information

Biogeochemical cycles play a dominant role on our globe. The nitrogen cycle is characterised by a huge reservoir of inert nitrogen and smaller amounts of active nitrogen in different chemical forms, including both oxidised and reduced nitrogen compounds. Chemical and biological processes result in transformation from one form into another. Without human interference, the nitrogen cycle is in equilibrium with no serious accumulation of forms of nitrogen leading to disturbance. Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for all forms of life in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, including humans. Nitrogen is also a growth-limiting nutrient in most of these systems. Because of this limitation, a rich biodiversity with very rare species has developed throughout the centuries.

Human activities aim at enhancement of the biological systems with respect to higher yields — both the productivity per unit and the geographic extent of biological activities. Human activities also include the use of oil, natural gas and biomass, resulting in release of CO2 and nitrogen. These processes are characterised by chemical conversions, meaning that there will be an output of non-intended products or wastes. In general, the ecosystems in which human activities are embedded are capable of absorbing these wastes without serious damage to other processes in the ecosystem. This capacity for internal removal of non-intended products is tied to critical limits and boundaries. In areas with high densities of human activities, environmental problems arise relating to excess of nitrogen.

2.1 Effects

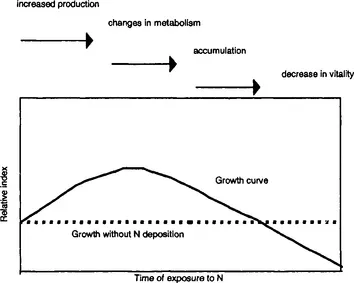

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for all plants, humans, animals, and micro-organisms. Because of this, nitrogen emissions are not harmful to the environment until they reach a certain level. For each system, there is an optimum nitrogen level related to the optimum production of the system. Ecosystems show an optimum curve. Figure 1 shows a temporal form of the optimum nitrogen curve for forest growth, as suggested by Gundersen (1992). It indicates that up to a certain optimum level, production increases and above that level production decreases.

Fig. 1 Hypothetical growth curve (Gundersen, 1992).

Increased amounts of all oxidised forms of nitrogen (NO, NO2, N2O5, NO3, HNO2, HNO3 and PAN) play a role in atmospheric pollution, deposition and soil and water pollution. Reduced forms of nitrogen, such as ammonia, ammonium and amines also play an important role in atmospheric pollution, deposition, soil and water pollution. N2O is a greenhouse gas ...