Abstract:

This chapter reviews the need to improve key learning outcomes of engineering education, among them conceptual understanding, solving real problems in context, and enabling skills for engineering such as communication and teamwork. At the same time it is necessary to improve both the attractiveness of engineering to prospective students and retention in engineering programmes. Research suggests that to address these problems the full student learning experience needs to better affirm students’ identity formation. Student feedback is identified as a key source of intelligence to inform curriculum and course development. An argument is made for clarifying the purpose of any student feedback system, as there is an inherent tension between utilising it for accountability or for enhancement. An example shows how enhancement is best supported by a rich qualitative investigation of how the learning experience is perceived by the learner. Further, a tension between student satisfaction and quality learning is identified, suggesting that to usefully inform improvement, feedback must always be interpreted using theory on teaching and learning. Finally, a few examples are provided to show various ways to collect, interpret and use student feedback.

Introduction

The aim of this book is to provide inspiration for enhancement of engineering education using student feedback as a means. It is important to recognise that enhancement is a value-laden term, and the course we set must be the result of the legitimate claims of all stakeholders, among them students, society, employers and faculty. As external stakeholders society and employers are mainly interested in the outcomes of engineering education – such as the competences and characteristics of graduates, the supply of graduates and the cost-effectiveness of education. Students and faculty share an additional interest in the teaching and learning processes, as internal stakeholders. Here, student feedback will be discussed as a source of information which can be productively used to improve engineering education – both the outcomes and processes – in the interest of all the stakeholders. As will be shown, the focus on enhancement has far-reaching implications for shaping an approach to collecting, interpreting and utilising student feedback: the keyword is usefulness to inform improvement.

Improving the outcomes of engineering education

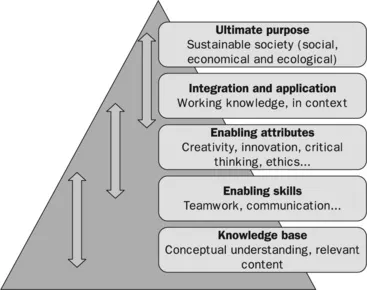

The desired outcomes of engineering education are shown in Figure 1.1, categorised into several layers. Each of these aspects can be the focus for improvement, and thus the underlying rationale for engineering education enhancement. Here the layers are nested in the sense that quality at any of the levels depends on the lower levels, and interrelations between the levels are crucial. An intervention to improve any one of the aspects needs to be seen in this full context. Ultimately, any outcomes of engineering education should be discussed in relation to the highest aim, which is to produce graduate engineers capable of purposeful professional practice in society.

Figure 1.1 Desired outcomes of engineering education

The target for improvement can range from a detail, such as students’ conceptual understanding of a single concept in the subject, to a much more complex outcome such as their overall ability to contribute to a sustainable society. Nevertheless, whatever aspect one wishes to enhance, it is always within the context of the full curriculum, and singling out one aspect and addressing it with an isolated intervention will therefore only have a limited impact. For instance, if the aim is to develop graduates who would be more innovative engineers, it is not enough to insert a single ‘innovation learning activity’, such as asking the students to brainstorm 50 ways to use a brick. This is indeed an enjoyable activity, but as a bolt-on intervention it will have a limited impact and fail to truly foster innovative engineers. A successful endeavour must address relevant aspects of the whole curriculum: selection of content, required conceptual understanding, integration and application of knowledge, and the enabling skills and attributes needed for innovation. At the same time, innovation must be seen in a purposeful context – innovation for what and for whom?

Improving problem-solving skills

The rhetoric in engineering education is that engineers are problem solvers, and therefore much effort in education is devoted to developing students’ proficiency in problem solving. In lectures, tutorials and textbooks, students encounter numerous problems, and they quickly develop the habit of plugging numbers into equations and arriving at a correct answer, remarkably often a neat expression like π/2. However, it is not unusual to discover that a significant proportion of students, even many of those who have successfully passed an exam, display poor understanding whenever they are required to do anything outside reproducing known manipulations to known types of problems.

Educators are often surprised and disappointed by this, because the intention was that students should be able to explain matters in their own words, interpret results, integrate knowledge from different courses and apply it to new problems. In short, an important outcome of engineering education is that students acquire the conceptual understanding necessary for problem solving.

But if problem-solving skills are important outcomes of engineering education, it is necessary to widen the understanding of what should constitute the problems. While students indeed encounter many problems in courses, an overwhelming majority are pure and clear-cut, with one right answer: they are textbook problems. In fact, they have been artificially created by teachers to illustrate a single aspect of theory in a course. Thus, much of students’ knowledge can be accessed only when the problems look very similar to those in the textbook or exam: what they have learned often seems inert in relation to real life. This is because real life consists mainly of situations that are markedly different from what students are drilled to handle. Real-life problems can be complex and ill-defined and contain contradictions. Interpretations, estimations and approximations are necessary, and therefore ‘one right answer’ cases are exceptions. Solving real problems often requires a systems view. In the typical engineering curriculum students seldom practice how to identify and formulate problems themselves, and they rarely practice and test their own judgement. Students are simply not comfortable in translating between physical reality and models, and in understanding the implications of manipulations. As engineering is fundamentally based on this relationship, it certainly seems as if engineering educators have some problems to solve in engineering education.

Real problems also have the troublesome character that they do not fit the structure of engineering programmes. Real problems cannot easily fit into any of the subjects because they do not have the courtesy to respect (the socially constructed) disciplinary boundaries. As both modules and faculty are organised into disciplinary silos, at least in the research-intensive universities, real problems seem to be outside everyone’s responsibility and the consequence is that students very rarely meet any problem that goes across disciplines. To make matters worse, real problems are not only cross-disciplinary within engineering, but as they are often rich with context factors such as understanding user needs, societal, environmental and business aspects, they cross over into subjects outside engineering. While many students’ first response is to define away all factors that are not purely technical and then give the remainder of the problem a purely technical solution, this solution is probably not adequate to address the original problem. Engineers also need to be able to address problems that have a real context.

If this list of shortcomings seems overwhelming, the good news is that the situation certainly can be improved, as the fault lies primarily in how engineering is taught and – not least – what is assessed and how, because ‘what we assess is what we get’. By constantly rewarding students for merely reproducing known solutions to recurring standard problems in exams, this is what engineering education is reduced to. Enabling students to achieve better and more worthwhile learning outcomes is necessary. Rethinking the design of programmes and courses also makes it possible.

Improving the enabling skills and attributes for engineering

While conceptual understanding and individual problem-solving skills are necessary outcomes of engineering education, they are not sufficient. As engineers, graduates must also be able to apply their understanding and problem-solving skills in a professional context. Because the aim is to prepare students for engineering, education should be better aligned with the actual modes of professional practice (Crawley et al., 2007). This means that students need to develop the enabling skills for engineering, such as communication and teamwork, and attributes such as creative and critical thinking.

It is important to think of these sk...