- 502 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forage in Ruminant Nutrition

About this book

Forage in Ruminant Nutrition is the 12th text in a series of books about animal feeing and nutrition. The series is intended to keep readers updated on the developments occurring in these fields. As it is apparent that ruminant animals are important throughout the world because of the meat and milk they produce, knowledge about the feeds available to ruminants must also be considered for increased production and efficiency. This text provides information that readers will find considerably invaluable about forage feeds, such as grass, legumes, hay, and straw. The book is composed of 16 chapters that feature the following concepts of ruminant forage feeding: • composition of ruminant products and the nutrients required for maintenance and reproduction; • energy and nutrient available in forage: calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, sodium, copper, iodine, zinc, manganese, selenium, and cobalt; • intake of forage by housed ruminants; • grazing; • forage digestibility; • protein in ruminant nutrition; • protein and other nutrient deficiencies. This volume will be an invaluable reference for students and professionals in agricultural chemistry and grassland and animal husbandry researches.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forage in Ruminant Nutrition by Dennis Minson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Agricultura. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Ruminant Production and Forage Nutrients

Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses the composition of ruminant products, the nutrients found in forage, and the nutrients that limit the ruminant production from forage. The identification of the optimum forage strategies for use on an individual property or in a region requires the knowledge of the different nutrients required for production, the ability of the forage to supply these nutrients, and the ways this deficiency can be prevented. The digestive tract of all herbivores contains bacteria, protozoa, and fungi capable of hydrolyzing cellulose, hemicellulose, and other substances resistant to digestion by enzymes secreted by the host animal. The microbial hydrolysis of forage is a slow process and the digestive tracts of herbivores are modified in various ways to increase the quantity of forage retained, and hence the time it is exposed to the microflora. In ruminants, the adaptation takes the form of an enlargement of the forestomach to form the reticulorumen and the ability to regurgitate and chew forage that is partially digested and softened in the reticulorumen.

I INTRODUCTION

Domestic ruminants are kept by humans to produce milk, meat, and wool from plant material, which, for the most part, is unsuitable for direct human consumption. In some cultures ruminants are also an important source of power (Copland, 1985), are utilized as wealth or status, and are ceremonial. Potential production of these animals has been raised during centuries of breeding and selection by humans, while losses in developed countries caused by disease, toxic plants, and bad husbandry practices have been reduced to low levels. Maximum production of meat, milk, or wool will be achieved only if animals are supplied with sufficient quantities of the raw materials required for the synthesis of those products. This can occur when housed ruminants are fed grain-based diets supplemented with protein, minerals, and vitamins, but when forage is the sole source of nutrients, production is invariably much lower than the genetic potential of the animal.

There are many available ways to improve the quality of forage-based diets and increase profit. Identification of the optimum forage strategies for use on an individual property or in a region requires a knowledge of the different nutrients required for production, the ability of the forage to supply these nutrients, how to identify which aspect of forage quality is failing, and the ways this deficiency may be prevented. Any potential solution must obviously take into account the relevant local economic, environmental, and social factors.

The digestive tract of all herbivores contains bacteria, protozoa, and fungi capable of hydrolyzing cellulose, hemicellulose, and other substances resistant to digestion by enzymes secreted by the host animal. Microbial hydrolysis of forage is a slow process and the digestive tracts of herbivores are modified in various ways to increase the quantity of forage retained and hence the time it is exposed to the microflora. In ruminants, the adaptation takes the form of an enlargement of the forestomach to form the reticulorumen and the ability to regurgitate and chew forage that has been partially digested and softened in the reticulorumen.

The quantity of each nutrient absorbed depends on (1) the quantity of forage dry matter eaten each day, and (2) the concentration and availability of that particular nutrient in each kilogram (kg) of forage dry matter (DM). The factors controlling voluntary food intake will be considered in Chapters 2 and 3, while the remaining chapters will consider the different nutrients that may limit ruminant production from forage.

This chapter will consider the composition of ruminant products, the nutrients to be found in forage, and those nutrients that could possibly limit ruminant production from forage and hence warrant further consideration in this volume.

II COMPOSITION OF RUMINANT PRODUCTS

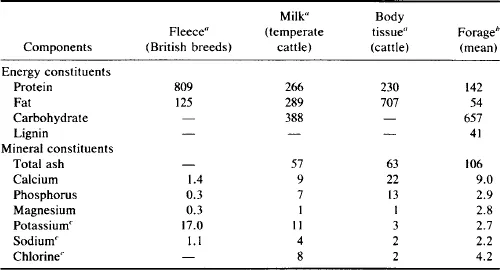

A Wool

The fleece of the sheep comprises three fractions: the actual wool fiber, suint (the secretion of the sweat glands), and fat (the secretion of the sebaceous glands). The relative proportions of these three fractions vary between breeds and managements. For British breeds of sheep a typical fleece contains 80% wool, 12% fat, and 8% suint (ARC, 1980). The wool fibers consist almost entirely of the protein keratin, which is characterized by a high content of cysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid. The chemical composition of clean dry fleece of British breeds is shown in Table 1.1.

TABLE 1.1

Mean Chemical Composition of Fleece, Milk, and Tissue Gain Produced by Ruminant Compared with the Nutrients in Forage (g/kg DM)

aFleece (ARC, 1980); milk (Armsby and Moulton, 1925; ARC, 1980). Growth composition at 400 kg empty body weight (ARC, 1980).

bTo be discussed in following chapters.

cUsually no field response to feeding these elements as supplements.

B Milk

The composition of milk produced by ruminants varies with species, breed, age, stage of lactation, and nutrition (ARC, 1980). The main constituent of milk is water, ranging from 83.6 to 87.3% for sheep and temperate cattle, respectively (Armsby and Moulton, 1925). Solids in the milk of temperate breeds of cattle contain approximately equal quantities of protein, fat, and carbohydrate, in the form of lactose (Table 1.1). The remaining solid consists of a range of mineral elements and vitamins (Table 1.1).

C Body Tissue

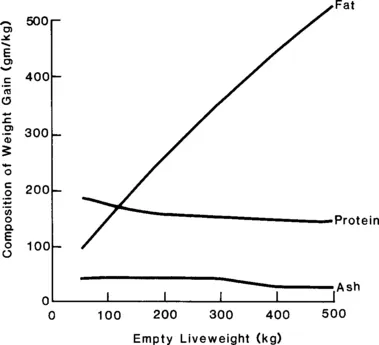

The body of ruminants is mainly composed of protein, fat, and water with a smaller quantity of mineral matter. With increasing maturity there is a decrease in the proportion of protein and an increase in the proportion of fat. For example, calves with an empty weight of 50 kg contain four times as much protein as fat, but by the time they reach 500 kg the body contains twice as much fat as protein (ARC, 1980). This change is due to the high fat content of new growth, particularly in mature animals (Fig. 1.1). At the final stages of cattle fattening, 86% of the energy which contributes to increased weight is stored as fat and only 14% as protein. Similar changes in body composition have been found in sheep (ARC, 1980). A small part of the gain in weight is in the form of bone. The main elements involved are calcium and phosphorus with smaller quantities of magnesium and sodium (Table 1.1).

Fig. 1.1 Effect of maturity on body composition of cattle. Adapted from Armsby and Moulton (1925) and ARC (1980).

III NUTRIENTS REQUIRED FOR MAINTENANCE AND REPRODUCTION

All animals require nutrients in order to maintain body processes and for reproduction. Energy is required for the muscular work of circulation and respiration and in mammals for maintaining body temperature.

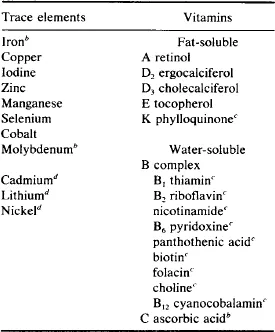

Muscles and enzymes have to be restored, and minerals unavoidably lost in the urine, feces, or sweat must be replaced. Trace elements and vitamins are also required (Table 1.2). The functions of these different nutrients are adequately reviewed in most standard texts on animal and human nutrition and only their availability to ruminants from forage will be considered in this volume.

TABLE 1.2

Trace Elements and Vitamins Required by Ruminantsa

aData from Nielsen (1984) and McDonald et al. (1988).

bUsually p...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- ANIMAL FEEDING AND NUTRITION

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Preface

- Terminology and Symbols Used

- Chapter 1: Ruminant Production and Forage Nutrients

- Chapter 2: Intake of Forage by Housed Ruminants

- Chapter 3: Intake of Grazed Forage

- Chapter 4: Digestible Energy of Forage

- Chapter 5: Energy Utilization by Ruminants

- Chapter 6: Protein

- Chapter 7: Calcium

- Chapter 8: Phosphorus

- Chapter 9: Magnesium

- Chapter 10: Sodium

- Chapter 11: Copper

- Chapter 12: Iodine

- Chapter 13: Zinc

- Chapter 14: Manganese

- Chapter 15: Selenium

- Chapter 16: Cobalt

- Glossary of Forage Names

- References

- Index