- 639 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Viral Ecology

About this book

Viral Ecology defines and explains the ecology of viruses by examining their interactions with their hosting species, including the types of transmission cycles that have evolved, encompassing principal and alternate hosts, vehicles, and vectors. It examines virology from an organismal biology approach, focusing on the concept that viral infections represent areas of overlap in the ecology of viruses, their hosts, and their vectors.

- The relationship between viruses and their hosting species

- The concept that viral interactions with their hosts represents a highly evolved aspect of organismal biology

- The types of transmission cycles which exist for viruses, including their hosts, vectors, and vehicles

- The concept that viral infections represent areas of overlap in the ecology of the viruses, their hosts, and their vectors

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section IV

Viruses of Macroscopic Animals

10

Ecology of Insect Viruses

LORNE D. ROTHMAN* and JUDITH H. MYERS†, *SAS Institute (Canada) Inc., Toronto, Ontario M5J 2T3, Canada; †Centre for Biodiversity Research, Departments of Zoology and Plant Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada

I. Introduction

II. Types of Viruses

III. Transmission

A. Horizontal Transmission

B. Vertical Transmission

C. Latent Virus

IV. Viruses and the Host Individual

A. Virulence

B. Debilitating Effects on Survivors

V. Viruses and the Host Population

A. General Theory

B. Mathematical Models

C. Experiments

D. Biological Control

VI. Synthesis: Evolution of Pathogen–Host Associations

References

I. INTRODUCTION

Insects, mostly in the orders Diptera (flies), Hymenoptera (e.g., sawflies, wasps, bees), Coleoptera (beetles), and particularly Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) are hosts to a variety of viruses. Research on insect viruses has focused on the more virulent pathogens of pests of forests and agriculture. However, the effects of viruses are extremely varied. Some cause spectacular epizootics and extensive mortality, while others are more benign and cause less obvious characteristics of disease. Recent advances in molecular biology have greatly improved our ability to identify and describe insect viruses and to study their behavior within the host. But to predict viral epizootics, or to successfully use virus to control pest species, we require a greater understanding of viral ecology. We do not provide an exhaustive review of insect host–virus interactions. Rather, we focus on some of the fundamental aspects of transmission, and effects of viruses on individuals and on host populations.

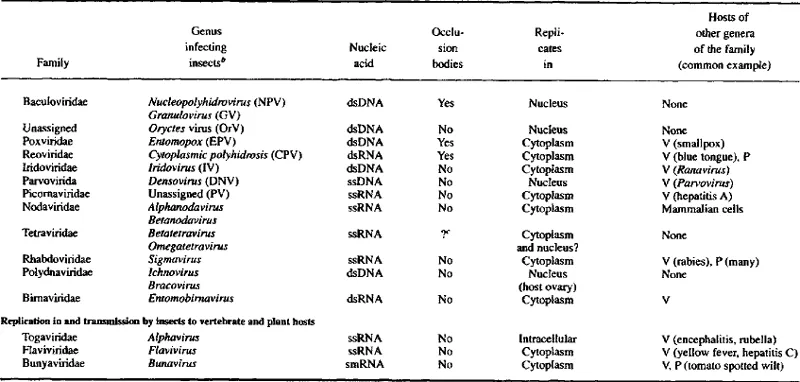

II. TYPES OF VIRUSES

We outline in Table I the major categories of insect viruses. Insect viruses can be categorized as being occluded or nonoccluded, of being DNA or RNA viruses, and of replicating in the nucleus or cytoplasm of cells. Except for the Baculoviridae and the Nudaurelia β virus group, families including entomoviruses also have forms that infect vertebrates or plants. The baculoviruses are specific to insects and have been the focus of the most study (Cory et al., 1997). Two major groups of baculoviruses are the nuclear polyhedral viruses (NPVs) and granulosis viruses (GVs), DNA viruses that replicate in the nuclei of cells. The virions of baculoviruses are encapsulated in protein occlusion bodies (OBs), which can be observed with a light microscope: 1–4 μm for NPVs and 0.1–0.5 μm for GVs. The protein matrix of the OBs protects the virions in the environment following the death of infected individuals.

TABLE I

Families and Genera of Viruses Associated with Insects Either as Pathogens or as Viruses that Replicate within the Insect and Are Transmitted to Vertebrate (V) or Plant Hostsa

aBased on ICTV (1995).

bAbbreviations of genera are in parentheses.

cMay sometimes be incorporated in occlusion bodies of baculoviruses (Moore, 1991).

III. TRANSMISSION

Two general pathways of virus transmission are horizontal, among individuals in the same generation, and between generations through environmental contamination, and vertical, directly from parents to offspring (Andreadis, 1987; Kukan, 1996).

A. Horizontal Transmission

Virulent pathogens such as nuclear polyhidrosis viruses (NPVs) and granulosis viruses (GVs) of Lepidoptera are primarily transmitted both within and between host generations through the release of OBs into the environment following death of infected individuals (Myers, 1993). Low levels of infectious virus can also be released in feces and regurgitate from the midgut in the late stages of infections (Vasconcelos, 1996). Less lethal pathogens are transmitted primarily in feces and regurgitate. This mode of transmission is important in Oryctes virus, cytoplasmic polyhidrosis viruses (CPVs), and entomopox viruses (EPVs) of some Lepidoptera, NPVs of sawflies, and small RNA viruses infecting bees (Sikorowski et al., 1973; Granados, 1981; Kelly, 1981; Payne, 1981, 1982; Zelazny and Alfiler, 1991; Myers and Rothman, 1995a). Oryctes virus is excreted by infected adult coconut palm rhinoceros beetles, Oryctes rhinoceros at breeding sites (coconut trunks) and while mating (Zelazny 1973, 1976; Zelazny and Alfiler, 1991; Zelazny et al., 1992; Kelly, 1981). The small RNA viruses, like the picornaviruses and sacbrood virus, cause chronic and acute honey bee paralysis. These viruses are likely secreted from salivary and hypopharyngeal glands into the liquid added by bees to the pollen as they collect it (Bailey, 1973; Kelly, 1981). In this way they are transmitted to other individuals. Although horizontal transmission usually occurs by ingestion of contaminated food such as foliage or egg chorion on hatching (discussed in what follows), iridescent viruses (IVs) of Aedes taeniarhynchus and Tipula oleracea (Diptera) (Linley and Nielson, 1968b; Carter, 1973a,b), and an NPV of Heliothis armigera (Dhandapani et al., 1993a) can be transmitted by cannibalism.

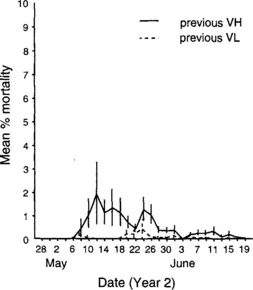

An example of host mortality following horizontal transmission of an NPV is illustrated in Figure 1. In this experiment, young tent caterpillars were fed leaves contaminated with NPV in the laboratory and then introduced to host colonies at two densities in the field. The first peak in mortality involves the lab-infected individuals that released NPV occlusion bodies when they died. Susceptible individuals ingested contaminated foliage and died about 2 weeks later, causing the second peak in mortality. Bi- and trimodal peaks of host mortality have been recorded for Pieris brassicae following experimental introduction of GV (Hochburg, 1991a) and for field populations of gypsy moth (Woods and Elkinton, 1987).

Fig. 1 Mean percentage mortality (+S.E.) of Malacosoma californicum pluviale (Lepidoptera) larvae from NPV observed at 2-day intervals in the year of introduction of NPV and host colonies at high (VH) and low (VL) larval and viral densities. Adapted with permission from Rothman (1997).

1. Persistence

Persistence of active virus in the environment or in the host population is important to the dynamics of within- and between-generation infection. Viruses in occlusion bodies are likely to persist longer than nonoccluded viruses. However, a nonoccluded small RNA virus of aphids was found to persist and be transmitted through plants (Gildow and D’Arcy, 1988). This interaction is more likely for sucking than chewing insects, but it suggests that more than plant surfaces may be involved in the persistence of insect viruses.

Foliage is an important substrate for short-term persistence of viruses. For example, Pringle and Lewis (1997) found that NPV of the celery looper Anagrapha falcifera was still 80% active after 9 days when sprayed onto silk of sweet corn. However, virus on foliage is generally deactivated in a matter of hours to days through exposure to ultraviolet sunlight (David et al., 1968; Jaques, 1972; Ignoffo et al., 1977; see Benz [1987] and Cory et al. (1997) for reviews). Roland and Kaupp (1995) and Rothman and Roland (1998) found reduced infection by NPV of the forest tent caterpillar Malacosoma disstria in forest-edge habitats compared to that in forest-interior habitats, which they attributed to faster deactivation by sunlight.

Many of the most lethal insect viruses produce infective stages that can persist outside the host for one or many seasons in the soil (see Benz, 1987; Entwistle and Evans, 1985; Cory et al., 1997), on tree bark, or on host eggs. In agricultural and pasture habitats, where hosts and host food plants are in close proximity, soil may be an important source of inoculum for host infections for NPVs, GVs, and EPVs (Hurpin and Robert, 1972; Jaques, 1975; Crawford and Kalmakoff, 1977). In forest systems, the mechanisms by which virus is transferred from soil to caterpillars are unclear, but wind, rain splash, and contamination of hosts, predators, and parasitoids are possible (Entwistle and Evans, 1985; Olofsson, 1988).

Host food plants are also important substrates for transgeneration virus transmission, particularly in forest systems. Woods et al. (1989) released neonate larvae of the gypsy moth Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera) onto sterilized, untreated,...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Preface

- Section I: Structure and Behavior of Viruses: An Introduction

- Section II: Viruses of Other Microorganisms

- Section III: Viruses of Macroscopic Plants

- Section IV: Viruses of Macroscopic Animals

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Viral Ecology by Christon J. Hurst in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Microbiology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.