- 420 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Liver Disorders in Childhood provides a comprehensive account of disorders of the liver and biliary system in childhood. Topics covered include the mechanisms of physiological jaundice; the link between jaundice and breast feeding; surgery for extrahepatic biliary atresia; the role of hepatitis B virus infection in chronic liver disease; presymptomatic diagnosis of Wilson's disease; liver transplantation; and surgical treatment of metabolic disorders such as glycogen storage disease. The main focus is on day-to-day practical problems of diagnosis and management from the viewpoint of the pediatrician. This book consists of 22 chapters and begins with an overview of the anatomy and physiology of the liver and the biliary tract. The discussion then turns to liver disorders such as conjugated and unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia; extrahepatic biliary atresia; infections of the liver; fulminant hepatic failure; and Reye's syndrome (encephalopathy and fatty degeneration of the viscera). Liver disorders caused by drugs or toxins are also considered, along with inborn errors of metabolism causing hepatomegaly or disordered liver function; familial and genetic structural abnormalities of the liver and biliary system; chronic hepatitis; and Wilson's disease. This monograph is written primarily for clinicians, especially pediatricians, paediatric surgeons and gastroenterologists, but will also be of value to pathologists, biochemists, and laboratory research workers concerned with understanding aspects of hepatic function and elucidating pathogenic mechanisms.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Anatomy and Physiology of the Liver

Publisher Summary

Clinical assessment of liver

Inspection

Palpation and percussion

Auscultation

Spleen

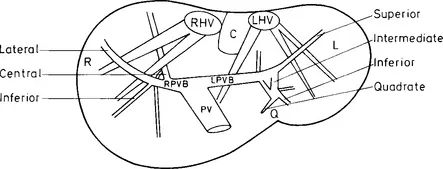

ANATOMY OF THE LIVER

Gross structure

Portal vein branches

Hepatic artery

Hepatic vein tributaries

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- POSTGRADUATE PAEDIATRICS SERIES

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Editor’s Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Anatomy and Physiology of the Liver

- Chapter 2: Anatomy and Physiology of the Biliary Tract

- Chapter 3: Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinaemia

- Chapter 4: Conjugated Hyperbilirubinaemia

- Chapter 5: Extrahepatic Biliary Atresia

- Chapter 6: Infections of the Liver

- Chapter 7: Fulminant Hepatic Failure

- Chapter 8: Reye’s Syndrome: (Encephalopathy and fatty degeneration of the viscera)

- Chapter 9: Liver Disorders Caused by Drugs or Toxins

- Chapter 10: Inborn Errors of Metabolism Causing Hepatomegaly or Disordered Liver Function

- Chapter 11: Familial and Genetic Structural Abnormalities of the Liver and Biliary System

- Chapter 12: Chronic Hepatitis

- Chapter 13: Wilson’s Disease

- Chapter 14: Cirrhosis and its Complications

- Chapter 15: Hepato-biliary Lesions in Cystic Fibrosis

- Chapter 16: Liver and Gallbladder Disease in Sickle Cell Anaemia

- Chapter 17: Indian Childhood Cirrhosis

- Chapter 18: Disorders of the Portal and Hepatic Venous Systems

- Chapter 19: Liver Tumours

- Chapter 20: Disorders of the Gallbladder and Biliary Tract

- Chapter 21: Laboratory Assessment of Hepatobiliary Disease

- Chapter 22: Investigation of Biliary Tract Disease

- Index