Following the discovery of the eosinophil in 1879, knowledge of its structure, functions, and role in disease has progressively increased. In this chapter the evolution of this knowledge is arbitrarily divided into five periods. The first period, from 1879 until approximately 1914, is defined by the contributions of Paul Ehrlich and colleagues. Ehrlich identified the eosinophil and established methods for its quantification in blood that are used to this day, leading to numerous associations with diseases, including asthma and helminth infection; his work led to the establishment of hematology as a medical specialty. The second period, from approximately 1915 to around 1970, was focused on the eosinophil and anaphylaxis. Numerous observations pointed to a role for eosinophils in tissue inflammation, possibly to counteract the damaging physiological effects from anaphylaxis. The third period, from approximately 1970 until the present, exploited advances in protein chemistry for the isolation and characterization of eosinophil granule proteins. Granule proteins are intensely basic molecules that both damage and stimulate cells and tissues. By tracking the proteins, associations with asthma and other allergic diseases were strengthened and a better understanding of eosinophil activity emerged. The fourth period, from approximately 1980 until the present, identified novel genes and analyzed proteins produced by gene expression. A critical advance was the discovery of interleukin-5, the most important molecule for eosinophil production in the bone marrow. The fifth period, since approximately 1990, witnessed the creation of disease models from transgenic mice and from other mice in which gene functions were eliminated or otherwise modified through a targeted mutation. Study of these mice has strikingly increased our knowledge of eosinophil function. Lastly, progress in understanding the eosinophil has not been confined to studies of the cell, itself, but also to diseases associated with eosinophilia.

Introduction

Since the time of its discovery by Paul Ehrlich, the eosinophil has been a challenge. To some, it is the most attractive cell in the body because of the beauty and brilliance of its cytoplasmic granules. To others, it is of little relevance because it is not an easy cell to put into a functional framework. Comparison with the neutrophil is instructive. The absence of neutrophils results in a marked increase in susceptibility to bacterial infections. In contrast, eosinophils are commonly reduced, often to very low numbers, in the blood by the administration of glucocorticoids. Yet, no definite consequences follow from this pharmacological eosinophil ablation.

I first saw an eosinophil in 1954 as a medical student, and, in the early 1960s, John H. Vaughan, my mentor at the University of Rochester, New York, USA, sparked my interest by commenting that asthma associated with eosinophilia is especially challenging. When I joined the staff of the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) in 1965, one of my duties was caring for hospitalized patients with asthma. At that time, we had relatively little to offer for outpatient treatment, and many patients were hospitalized. Treating them consisted of assuring that asthma was the correct diagnosis and initiating care with hydration and oral glucocorticoids, usually prednisone. Most patients quickly responded with improved respiration. As many as 20–25 asthma patients might be hospitalized at a time and they stimulated my interest in the pathophysiology of the disease.

Some were allergic to environmental allergens, but others were not and had blood eosinophilia associated with nasal polyps and sensitivity to aspirin. I collected sputum and found many eosinophils. I read reports on the pathology of asthma and I realized that knowledge of the eosinophil, including how it might affect asthma, was sparse. Around 1968, I decided to direct research efforts at Mayo to investigating the eosinophil. In this overview, I will interweave elements of the efforts of our laboratory and the work of many others to tell the story of the eosinophil from its recognition to the present. In describing the evolution of knowledge of the eosinophil in health and disease, I arbitrarily divide these developments into five periods based on the scientific understanding of the times, with overlap in the third, fourth, and fifth period.

The first period, from 1879 until approximately 1914, highlights the contributions of Paul Ehrlich. The advances during this period were based on the knowledge of chemistry, especially dyes. Ehrlich brilliantly applied chemicals used in the German dye industry to the microscopic examination of human cells and tissues, and, from this work, discovered the eosinophil. The application of his methods for the analysis of blood provided clues to eosinophil function by showing associations with asthma and parasitic diseases. His contributions also established hematology as a specialized area of clinical knowledge.

The second period, from approximately 1915 to around 1970, was based on the association of eosinophilia with anaphylaxis and the recognition that eosinophils accumulate in tissues after this calamitous inflammatory event. These observations pointed to a role for eosinophils in tissue inflammation, possibly to counteract the damaging physiological effects from anaphylaxis. Investigators during most of this period were hampered by the lack of technology needed for protein analyses and were forced to rely on associations that were difficult to explain mechanistically.

The third period, from approximately 1970 until the present, exploited advances in protein chemistry such that eosinophil granule proteins were isolated, characterized, and their functions defined. The affinity of the eosinophil for eosin is due likely to these intensely cationic protein molecules. Investigation of the granule proteins immediately suggested mechanisms for eosinophil function in disease. By tracking the proteins, associations with asthma and other allergic disorders were strengthened, and better understanding of eosinophil activity emerged.

The fourth period, from approximately 1980 until the present, employed new knowledge of genetics to identify novel genes and to express proteins. A critical advance using this technology was the discovery of factors controlling eosinophil production, especially interleukin-5 (IL-5). The fifth period, beginning approximately in 1990, took advantage of the ability to create disease models by generating mice with defined attributes, transgenic mice, and other animals in which gene functions were eliminated or otherwise modified through a targeted mutation, gene knockout and knock-in mice, respectively. These technologies led to the development of mice with increased numbers of eosinophils and mice with no eosinophils. Investigation of these mice has strikingly increased our knowledge of eosinophil function. Importantly, progress in our understanding of the eosinophil has not been confined to studies of the cell itself, but also to diseases associated with eosinophils, and I comment on significant disease discoveries.

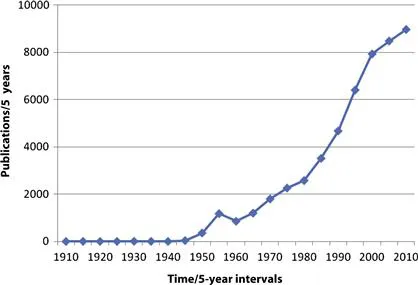

Fig. 1.1 shows the number of eosinophil citations from PubMed from 1910 to the present in 5-year periods and illustrates a striking increase from approximately 1960 until 2000 with the numbers of publications continuing to rise. These numbers are not simply a reflection of increased overall publications, because the percentage of eosinophil publications (total number of eosinophil citations in a 5-year period divided by the total number of publications in the same 5-year period) increased threefold from 1965–1969 to 1995–1999. This increased ratio reflects the increased attention paid to eosinophils by investigators over this time. The early literature on eosinophils is summarized by Schwarz in a monumental tome citing some 2758 references,1 while Samter provides a scholarly and insightful analysis of advances from about 1915 until about 1970.2

FIGURE 1.1 Citations for eosinophil listed in PubMed per five-year period.

This information suggests that very few publications occurred before about 1940. However, PubMed does not track the German literature of the early 1900s and before, and, therefore, many publications are not accounted for. As noted in the chapter, Schwarz published a review of the eosinophil in 1914 containing some 2758 references.1

Paul Ehrlich and the Discovery of the Eosinophil

A superb account of Paul Ehrlich’s life and his accomplishments was written by Hirsch and Hirsch.3 They describe his life and career in detail, and a short synopsis is recounted here. Ehrlich was born in 1854 in Germany and was a good, though not outstanding, student as a child. He moved from school to school during his university education and published his first paper, Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Anilinfärbungen und ihrer Verwendung in der mikroskopischen Technik (translated from German as Contributions to the Knowledge of Aniline Dyes and Their Use in Microscopic Techniques), while still a medical student. After his graduation in 1878, he accepted a position at the Charité-Universitätsmedizin hospital in Berlin where he spent the next nine years in productive research making observations on clinical cases and on hematology and histochemistry. From 1888 to 1890, he developed a persistent productive cough and found tubercle bacilli in his own sputum. He spent the winter in southern Italy and Egypt to rest and recover. After returning to Berlin, he was jobless and, with support from his wife’s parents, established a small laboratory in an apartment.

In 1890, Robert Koch, the discoverer of the tubercle bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, secured a post for him as head of a clinical observation station in Berlin, and, in 1896, Ehrlich was given government support and facilities. During the period from 1890 until 1905, he pursued work in immunology, developing methods for producing high levels of antibodies and for quantitating the potency of antisera, and on the toxophore and haptophore groups and the side–chain theory. Ehrlich shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Ilya Mechnikov in 1908 for their contributions to immunology. In about 1905, Ehrlich turned his attention to chemotherapy, culminating in successful clinical trials of arsphenamine for the treatment of syphilis in 1910. He died in 1915 at the age of 61 of diabetes with cardiovascular and renal disease. With his death, the early period of eosinophil research ended.

Ehrlich had the good fortune to be the beneficiary of a remarkable blossoming of chemistry in Northern European countries such as England, France, and Germany. In 1824, Justus von Liebig had established the world’s first major school of chemistry and taught a generation of chemists, including names that have become bywords for chemistry, such as August Kekulé, Emil Erlenmeyer, and August Wilhelm von Hofmann. Von Hofmann determined the nature of aniline and laid the scientific basis for the dyestuff industry. In 1865, Friedrich Engelhorn established the Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik (Baden Aniline and Soda Factory; BASF), and that company came to exemplify a special symbiosis between business and scientific research.4 Heinrich Caro was trained in the laboratory of Robert Bunsen and joined BASF in 1868. He is regarded as being responsible for the company’s successes in the dye industry and developed methylene blue. He and his colleagues built the company from a small enterprise to an international giant on the basis o...