eBook - ePub

Education and Training for the Oil and Gas Industry: Case Studies in Partnership and Collaboration

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Education and Training for the Oil and Gas Industry: Case Studies in Partnership and Collaboration

About this book

Volume 1: Education and Training for the Oil and Gas Industry: Case Studies in Partnership and Collaboration highlights, for the first time, 8 powerful case studies in which universities, colleges and training providers are working with oil companies to produce capable, competent people.

This essential companion in our series illustrates not only the carefully researched details of the partnerships and collaborative activities, but also offers commentary on each of the cases from Getenergy's decade of experience in uniting universities, colleges, training providers and the upstream oil and gas industry on a global basis.

- Edited by Getenergy's Executive Team which—for more than a decade—has uniquely specialized in mapping and connecting the world of academia and learning with the upstream oil and gas industry through events and workshops around the globe.

- Detailed research into the key facts surrounding each case with analysis to enable readers to quickly and effectively extract the lessons and apply to a variety of challenges in building oil/gas workforce capacity.

- Highlights the business lessons for universities, colleges and training providers from collaborative working to support skills projects for major companies where demand is greatest.

- Includes full colour images and partnership diagrams' to underscore key concepts

- Offers a unified and universal case study rating mechanism in which readers can participate on-line to be part of this important and varied community.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Education and Training for the Oil and Gas Industry: Case Studies in Partnership and Collaboration by Phil Andrews,Jim Playfoot in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Chemical & Biochemical Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Case Study 1

ENI, Mattei and Boldrini

A Radical Response to the Challenges of Developing International Energy Expertise

Abstract

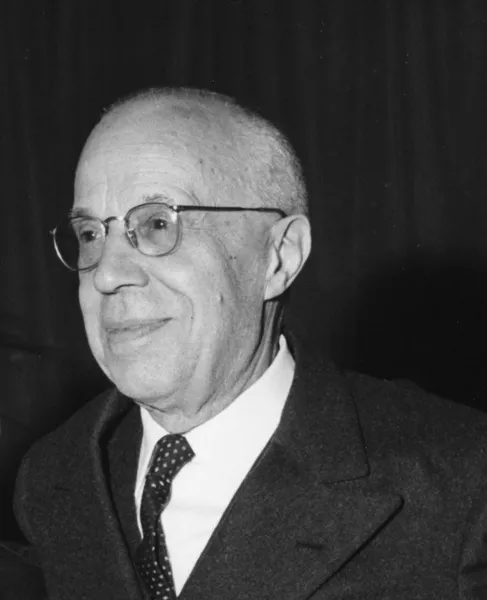

This case study considers the establishment of the ENI Graduate School for the Study of Hydrocarbons in 1957 under the guidance of Enrico Mattei and Marcello Boldrini. The Graduate School was set up to provide education and development to the next generation of energy leaders and, crucially, was open to candidates from overseas as well as those from within Italy. The School was radical as it embraced a multi-disciplinary approach to the development of its students and, within this context, challenged the pervading models of operation that had developed within the industry over previous decades. Many of the graduates of the School went on to perform critical roles within the energy industry of their native countries with some leading the growth of national oil companies within emergent energy nations. Mattei's vision was to both support the development of individuals who could free their country from the grip of the international oil companies and to ensure that those individuals had strong and positive connections to ENI so that positive partnerships would emerge over time. This case study considers how Mattei and Boldrini achieved their vision, the level of success they achieved and the legacy they left behind.

Keywords

Education as cultural diplomacy; ENI; Enrico Mattei; Graduate School for the Study of Hydrocarbons; Marcello BoldriniThis case study has been written by Elisabetta Bini, Research Fellow, University of Trieste.

The Motivation

Between the second half of the 1950s and the late 1960s, as oil producers emerged as important international actors, the national oil company of Italy—Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi (ENI)—and its charismatic leader Enrico Mattei recognised the emergent challenges around developing energy resources across the world and supporting this development through education.

As a company that lacked the power, influence and resources enjoyed by international oil firms (which were the dominant force in the energy industry globally), ENI needed to find a way to build relations with the new elites in charge of ruling their countries after the achievement of national independence, in order to establish long-term connections and secure an international future for ENI.

At the same time ENI—and Mattei in particular—recognised the right of oil-producing countries to control their own oil and gas activities and embraced the idea that those who would be responsible for the energy industry needed to be supported to become the future leaders and practitioners in their own countries. In this way, the growth of the energy industry could contribute to decolonising these nations and could support a transition to economic and political independence.

Mattei saw ENI as having an important role to play in transforming the relationship between Western Europe/the US and oil producers and was interested

in finding a way of building the knowledge, capacity and capability of African, Asian, Latin American and Middle Eastern students.

ENI and Mattei were also looking for a mechanism by which the rules of the international oil market could be redefined by balancing oil-producing and oil-consuming countries around a common interest: to challenge the power of the oil cartel and empower emergent nations to take control of their own energy industries.

The Context

ENI started life in 1926 when the Italian government established the Azienda Generale Italiana Petroli (AGIP) as a state-owned company with the aim of pursuing petroleum exploration, refining and distribution in Italy and the colonies, as well as Romania and Albania, in order to achieve the country’s independence from the import of coal and oil from abroad. During World War II, most of AGIP’s refineries, pipelines and drilling equipment were either destroyed or heavily damaged, while its tanker fleet was virtually eliminated. With the landing of the Allies in Sicily in the Summer of 1943 and the division of Italy in two separate parts, the country’s provisional government, with the support of the US, Great Britain and the international oil companies, promoted the liquidation of AGIP.1

However, thanks to the role of the Centre-Left Christian Democrats, as the war was coming to an end in Northern Italy, Mattei was nominated as Special Administrator of AGIP Alta Italia, with the task of supervising the company’s activities in Northern Italy. Mattei saw AGIP as a principal mechanism by which the country could emerge from the post-war economic slump and drew on the expertise of a small group of Italian geologists who had made important discoveries of natural gas (and later oil) in the Po Valley. This activity became a symbol of Italy’s reconstruction and potential energy independence from US and British oil companies.2

The creation of ENI, a single organisation responsible for all of Italy’s activities in the hydrocarbon sector, was Mattei’s vision. As a member of the Italian Parliament, Mattei had lobbied for the establishment of the company and received support from Christian Democrats such as Ezio Vanoni and Giovanni Gronchi, who promoted the nationalization of the energy industry. On February 10, 1953, ENI was established by an act of Parliament as the national hydrocarbons company for Italy and placed under the direction of Mattei. The organisation drew together a wide number of disparate publicly owned entities (comprising exploration, refining, transport and distribution) into a single holding and gave Mattei the basis for expansion across Italy and beyond.3

During the 1950s and 1960s, as ENI developed operations in Italy with the production and distribution of natural gas and, to a lesser extent, oil, it also increased its presence internationally, particularly in North Africa and the Middle East. Through what came to be known as the “Mattei formula”, ENI challenged the established models of operation involving the large private oil companies and explored new models of collaboration and partnership. It assigned oil-producing countries wider control over their oil resources by subverting the so-called “50-50 rule”, which regulated the international oil market. Not only did ENI assign oil producers control over 75% (rather than 50%) of their oil revenues, but it recognised oil-producing countries as partners in the exploration and production of hydrocarbons. According to its treaties, while ENI would be responsible for covering all exploration costs, once it located a new source of oil and gas production, states would participate in the exploration and refining of oil side by side with the Italian company with their workers being trained in Italy.4

The scale of ENI’s international activities grew steadily during the 1950s with a joint venture announced with the Egyptian government in 1955, and then similar agreements signed with Iran in 1957, Morocco in 1958, Libya and Sudan in 1959, Tunisia in 1961 and Nigeria in 1962. The effect of ENI’s activities in Africa and the Middle East was to stimulate and support the emergence of state oil enterprises abroad, and deepen the connection between ENI and these national oil companies. ENI’s policies were driven partly by ideology—Mattei believed in supporting the autonomy and independence of emergent energy nations—and partly by sound business acumen. By offering oil producers improved terms in relation to profit sharing and production rights, ENI—a national oil company with a fraction of the global power and influence of the feted “seven sisters”—could begin to establish itself on the international stage.5

ENI faced a series of issues particular to its activities. The growing complexity of the international oil market and the tensions that emerged during the 1950s and 1960s between oil-producing and oil-consuming countries drove several oil firms to redefine the role of engineers, geologists and technicians, and placed the issue of education at the forefront of discussion. Members of the industrial as well as the academic worlds were increasingly aware of the need for undergraduate and graduate schools to undergo a transformation. Schools needed to provide their students with more than just the technical knowledge necessary for the exploration and extraction of hydrocarbons by exposing them to a variety of disciplines including economics and the humanities.

From the beginning, Mattei realised that this endeavour was not only about money. Part of the deal had to be about building capacity and supporting the development of human capability in countries where national elites were often ill-equipped to make decisions and lacking in opportunities to build their knowledge, expertise, and understanding. Mattei and his Vice President at ENI Marcello Boldrini recognised the need to support workforce development in oil-producing

countries and instruct an elite of high calibre individuals who could lead the future development of the energy industry within their own country.6

The Solution

In 1957, ENI—under the guidance of Boldrini—established the Scuola di Studi Superiori sugli Idrocarburi (the Graduate School for the Study of Hydrocarbons). Its aim was to create a place of higher learning capable of developing an international elite that could be employe...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Preface

- About Getenergy

- About the Authors

- The Case Studies

- Case Study 1. ENI, Mattei and Boldrini: A Radical Response to the Challenges of Developing International Energy Expertise

- Case Study 2. The University of Trinidad and Tobago: A University Designed and Built in Partnership with Industry

- Case Study 3. exploHUB: Developing the Next Generation of Energy Explorers

- Case Study 4. Australian Centre for Energy and Process Training (ACEPT): A State-Funded Training Facility Built on Industry Partnerships

- Case Study 5. Takoradi Polytechnic and the Ghanaian Energy Industry: An Education/Industry Partnership to Build an Energy Workforce for Ghana

- Case Study 6. NorTex Petroleum Cluster: An Industry/Academic Partnership to Develop the Energy Professionals of the Future

- Case Study 7. Penspen and Northumbria University: A Partnership to Develop the Next Generation of Pipeline Engineers

- Case Study 8. ShaleNET: A Partnership to Develop Entry-Level Candidates for the Marcellus Shale Play

- End Note

- Index