- 369 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This unique book provides an integrated view of human facial expressions based on contemporary knowledge about the evolution of signaling across the animal kingdom. Spanning fields that range from psychology and neurology to anthropology and linguistics, it reopens and discusses some of the classic questions in the field, including: What do facial expressions express? What are the relations between facial expressions and our motives and emotions? How did our facial expressions evolve? Are there really innate and universal facial expressions?Human Facial Expression is suitable for graduate and advanced undergraduate use as a text or course supplement. Chapters on the history of interpreting facial expressions, and on Darwin's contributions, set the stage for a thorough discussion of modern evolutionary theory and the biological, cultural, and developmental origins of our facial expressions. The incorporation of recent findings on the syntactics and semantics of animal signaling show the fundamental link of human facial expressions to vocalization and language.

- Coverage includes methodology in evolutionary research

- Introductory discussion of facial nerves and muscles

- Compares and contrasts emotion vs. behavioral ecology views of facial expressions

- Cross-cultural analysis of similarities and differences in facial expressions

- Reviews paralanguage and gesture

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

PRE-DARWINIAN VIEWS ON FACIAL EXPRESSION

Publisher Summary

Physiognomy was the classical practice of facial morphology or face reading. Even during earlier periods when physiognomy was especially in vogue, the belief was pervasive that the face was the window to the soul. This tradition of classical physiognomy characterized traits from the conformation of the face despite the range of factors that may have produced it. The range of facial morphological contortions that were visible to the observer, that Leibniz labeled as passions, were believed to give away a person’s true feelings. Until the nineteenth century, interest in the face was primarily morphological and physiognomic, and most observers abided by Aristotle’s skepticism about whether fleeting facial movements were at all worth studying. Thereafter, interest in facial movements grew as the result of a number of factors. Pre-Darwinian evolutionists attempted explanations to account for facial muscular actions; pre-Darwinian evolutionist Lorenz Oken believed that the bones and muscles of the head were but transformed extremities. While, Charles Bell in his Essays on the anatomy of expression in painting, 1806, attempted to explain facial actions simply as indicating pleasant versus unpleasant sentiments. Darwin’s account of facial expression attempted to link icon like faces with discrete basic emotions. Darwin’s attack took the form of a volume on the face and emotion, the Expression of the emotions in man and animals.

The current practice of reading “emotion in the human face” is only the most recent of many. Preoccupation with facial morphology came first, in the practice of face-reading known as physiognomy.

THE RISE AND FALL OF PHYSIOGNOMY

“Face-reading” goes back to classical antiquity. It existed in ancient Egypt and Arabia, and was a profession in China before Confucius. In Chinese face-reading, for example, a high forehead portended good fortune, the eyes indicated energy and intelligence, the nose symbolized wealth and achievement, and the mouth conveyed the personality. The Chinese also studied facial asymmetry. The left side of the face was Yang, masculine and paternal, whereas the right side was Yin, feminine and maternal. A symmetrical face implied psychological balance (Landau, 1989).

Pythagoras probably began the scientific study of physiognomy, and reportedly selected his pupils based on their facial features. Hippocrates and Galen both incorporated physiognomy in their medical diagnoses (Tytler, 1982). Socrates was charged by a physiognomist with having a face that indicated brutality and an excessive love for women (Wilson & Herrnstein, 1985; Tytler, 1982).

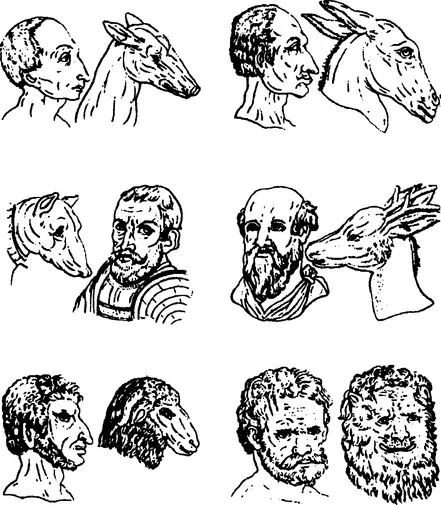

The first treatises on physiognomy (e.g., the Physiognomonica and the Historia animalium) are usually attributed to Aristotle. They were written approximately 340 B.C., but even by then physiognomic systems were common. Aristotle noted attempts by predecessors to compare the physical characteristics of several peoples (Egyptians, Thracians, Scythians) with the intent to understand them psychologically, but was cautious about the conclusions. Ever the empiricist and biologist (he, like Darwin, was an insatiable specimen collector), he believed that physiognomic traits were best discerned by comparing people with animals. He thus anticipated Darwin by 2200 years by recommending the “comparative method” for understanding the meanings of faces (more on this in Chapter 3).

Aristotle provided several cross-species interpretations. Fat ears like an ox’s indicated laziness. Men with prominent upper lips were, he contended, stupid like apes and donkeys. Noses called for special interpretation: fat noses like the pig’s signified stupidity, pointed noses like the dog’s implied a choleric temperament. People with flat noses like the lion’s were generous, whereas those with “hawk” noses like the eagle’s were magnanimous. The hair on one’s head was also meaningful. Fine hair (like that of stags, rabbits, and sheep) meant timidity, but rough hair (like that of lions and boars) implied courage.

In propounding his physiognomy, Aristotle downplayed the reading of sentiments from facial expressions. Although the “passions” certainly showed in the face, he considered them so variable and short lived that they were scarcely informative and gave no clue to the lasting, important character traits discernible through physiognomy (Piderit, 1886).

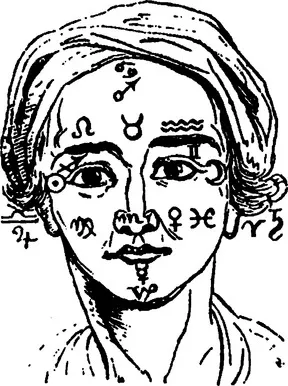

During the Middle Ages, Europe’s turn away from naturalism toward the occult had its effect on physiognomy. Facial morphology now provided clues not to temperament but to fate, and face-reading joined the astrologer’s armamentarium along with numerology, soothsaying, and palmistry. This physiognomy was cosmological: for example, the lines on the forehead were named for planets (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 The physiognomy of the Middle Ages diverged from its basis in Aristotle’s comparative anatomy and became an astrological technique. Lines in the forehead, for example, were named for the five known planets. From Landau (1989).

The Renaissance figure Giambattista Delia Porta resurrected Aristotle’s comparative method and melded it with the Hippocratic typology of temperament. In his 1586 De humana physiognomonia, Delia Porta interpreted faces and heads based on their likenesses to animals (Figure 1.2), and detailed how specific facial features could diagnose whether one was sanguine, phlegmatic, melancholy, or choleric. On the basis of his theory, Delia Porta found Plato to be most similar to a canny hunting dog. Delia Porta attained wide prominence as a physiognomist, and De humana physiognomonia eventually reached 20 editions and numerous translations.

FIGURE 1.2 Renaissance physiognomist Giambattista Delia Porta resurrected Aristotle’s methods of deducing traits from physiognomic similarities to animals (as depicted by Lavater).

But the greatest expositor of physiognomy was also the most responsible for its disrepute: Johann Caspar Lavater. Lavater was an eighteenth-century Swiss Protestant pastor and poet who believed that he was imbued with special expertise at recognizing the God in humans through the divination of traits from the shapes and lines in the face. His frequent public talks were spiced with oracular physiognomic readings, and he pleaded with Elmer Gantry-like messianic fervor for the widespread use of physiognomy to improve the lot of humanity. This was the message throughout his four-volume exegesis, Fragments of physiognomy for the increase of knowledge and love of mankind, published from 1775 to 1778. These volumes became best sellers, and his public persona and personal charisma gained him many illustrious adherents. Among the many who made pilgrimages to Zurich for special audiences was Goethe, who became his friend and traveling companion.

Lavater opposed any scientific physiognomy, and he constantly invoked the physiognomist’s (i.e., his) expertise as against scientific objectivity. Piderit (1886) cites from the Essays:

What folly it is to make physiognomy into a science so that one can speak on it or write about it, hold seminars or listen to them! (p. 72)

What is science in which everything can be determined, nothing is left to taste, feelings, genius. Woe to science, if it were such! (p. 71)

Lavater’s methods of interpretation were inscrutable, and his own descriptions of his methods are vague and condescending (“anyone with any physiognomic talent will agree that …”).

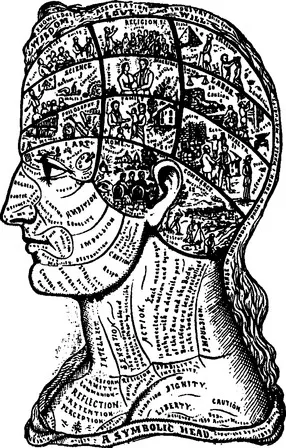

For better or worse, physiognomy became identified with Lavater, and though not without its critics, Lavaterian physiognomy swept Europe through the late eighteenth century, when it was overshadowed by the newest morphological enterprise, the phrenology of Franz Joseph Gall. Despite Gall’s antipathy for Lavaterian physiognomy and his desire to keep phrenology separate, the two were often practiced together. Face-reading revealed one’s character, while phrenological bump-reading elucidated one’s reason, memory, and imagination (Tytler, 1982). Face-reading became part of “having one’s head examined” (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3 The rise of phrenology saw the incorporation of physiognomy, with mental faculties read from the head and character interpreted from the face. From Rosensweig and Leiman (1982).

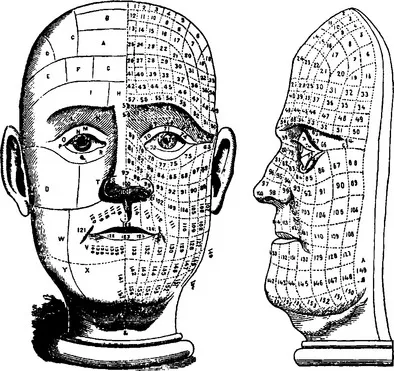

Not content to cede to the phrenologists the “hard data” provided by cranial landmarks, a few physiognomists began to construct equally analytical systems. In some cases, these new analytical physiognomies used both bony and muscular landmarks to discern character traits. These landmarks were numerous, and their correlated traits were broad. This lent an air of exactitude but still allowed ample opportunity for the usual physiognomic proclamations (Figure 1.4).

FIGURE 1.4 Physiognomy was eventually extended to include both the bony landmarks and the muscular contours of the face (anatomical left and right sides, respectively). This system by Redfield probably constituted the apotheosis of physiognomic complexity. From Wells (1871).

Compared to the phrenologists, early nineteenth-century physiognomists were less concerned with clinical practice than with assembling woodcuts, lithographs, and daguerreotypes of historical figures and then providing characterological commentaries. These commentaries foreshadowed today’s psychobiographies. Physiognomy affected descriptions of character in nineteenth-century novels (Tytler, 1982), and so that artists could create accurate renderings of character, physiognomy also became part of formal training in aesthetics.

By the mid-nineteenth century, physi...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Chapter 1: PRE-DARWINIAN VIEWS ON FACIAL EXPRESSION

- Chapter 2: DARWIN’S ANTI-DARWINISM IN EXPRESSION OF THE EMOTIONS IN MAN AND ANIMALS

- Chapter 3: FACIAL EXPRESSION AND THE METHODS OF CONTEMPORARY EVOLUTIONARY RESEARCH

- Chapter 4: MECHANISMS FOR THE EVOLUTION OF FACIAL EXPRESSIONS

- Chapter 5: FACIAL HARDWARE: THE NERVES AND MUSCLES OF THE FACE

- Chapter 6: FACIAL REFLEXES AND THE ONTOGENY OF FACIAL DISPLAYS

- Chapter 7: EMOTIONS VERSUS BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY VIEWS OF FACIAL EXPRESSION: THEORY AND CONCEPTS

- Chapter 8: EMOTIONS VERSUS BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY VIEWS OF FACIAL EXPRESSION: THE STATE OF THE EVIDENCE

- Chapter 9: INTRODUCTION: CROSS-CULTURAL STUDIES OF FACIAL EXPRESSIONS OF EMOTION

- Chapter 10: IS THERE UNIVERSAL RECOGNITION OF EMOTION FROM FACIAL EXPRESSION? A REVIEW OF THE CROSS-CULTURAL STUDIES

- Chapter 11: HOW DO WE ACCOUNT FOR BOTH UNIVERSAL AND REGIONAL VARIATIONS IN FACIAL EXPRESSIONS OF EMOTION?

- Chapter 12: FACIAL PARALANGUAGE AND GESTURE

- Chapter 13: EPILOGUE: THE STUDY OF FACIAL DISPLAYS—WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

- REFERENCES

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Human Facial Expression by Alan J. Fridlund in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.