DONALD P. McDONNELL, Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710

I. Introduction

II. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors

III. Established Models of Estrogen and Progesterone Action

IV. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Isoforms and Subtypes

V. Regulation of Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Function by Ligands

VI. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Associated Proteins

VII. An Updated Model of Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Action

References

I. INTRODUCTION

The steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone are small molecular weight lipophilic hormones that, through their action as modulators of distinct signal transduction pathways, are involved in the regulation of reproductive function [1,2]. These hormones have also been shown to be important regulators in bone, the cardiovascular system, and the central nervous system [3–5]. Despite their different roles in these systems, however, it has become apparent that estrogens and progestins are mechanistically similar [6]. Insights gleaned from the study of each hormone, therefore, have advanced our understanding of this class of molecules as a whole. This review highlights some of the recent mechanistic discoveries that have occurred in the field, and explores the subsequent changes in our understanding of the pharmacology of this class of steroid hormones.

II. ESTROGEN AND PROGESTERONE RECEPTORS

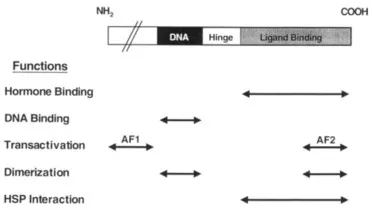

The estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) cDNAs have been cloned and used to develop specific ligand-responsive transcription systems in heterologous cells, permitting the use of reverse genetic approaches to define the functional domains within each of the receptors [6]. A schematic that outlines the organization of the major functional domains within these two steroid receptors (SR) proteins is shown in Fig. 1. The largest domain (∼300 amino acids) that is responsible for ligand binding is located at the carboxyl terminus of each receptor. Crystallographic analysis of the agonist-bound forms of ERs and PRs has indicated that this domain consists of 12 short α-helical structures that fold to provide a complex ligand-binding pocket [7,8]. The ligand-binding domain also contains sequences that facilitate receptor homodimerization and permit the interaction of apo receptors with inhibitory heat-shock proteins. An activation function (AF-2) required for receptor transcriptional activity is also contained within the ligand-binding domain [9,10]. An additional activation function (AF-l) is located within the amino terminus of each receptor [11].

FIGURE 1 Established models of estrogen and progesterone action. The classic models of estrogen and progesterone action suggested that, in the absence of ligand, the steroid receptor (SR) exists in the nuclei of target cells in an inactive form. On binding an agonist, the receptor would undergo an activating transformation event that displaces inhibitory heat-shock proteins (HSP) and facilitates the interaction of the receptor with specific DNA steroid response elements (SRE) within target gene promoters. The activated receptor dimer could then interact with the general transcription machinery and positively or negatively regulate target gene transcription. In this model the role of the agonist is that of a “switch” that merely converts the ER or PR from an inactive to an active form. Thus, when corrected for affinity, all agonists would be qualitatively the same and evoke the same phenotypic response. By inference, antagonists, compounds that oppose the actions of agonists, would competitively bind to their cognate receptors and freeze them in an inactive form. As with agonists, this model predicted that all antagonists are qualitatively the same. Within the confines of this classic model it was difficult to explain the molecular pharmacology of the known ER and PR agonists and antagonists. GTA, General transcriptional activity.

The DNA-binding domain (DBD) is a short region (∼ 70 amino acid residues) located in the center of the receptor protein [12]. This.permits the receptor to bind as a dimer to target genes. Within the DBD there are nine cysteine residues, eight of which can chelate two zinc atoms, thereby forming two fingerlike structures that allow the receptor to interact with DNA [13]. All of the information required to permit target gene identification by ligand-activated ERs and PRs is contained within this region.

III. ESTABLISHED MODELS OF ESTROGEN AND PROGESTERONE ACTION

The steroid hormones estrogen and progesterone are representative members of a larger family of steroid hormones, all of which appear to share a common mechanism of action. It is generally believed that steroid hormones enter cells from the bloodstream by simple passive diffusion, exhibiting activity only in cells in which they encounter a specific high-affinity receptor protein [14]. These receptor proteins are transcriptionally inactive in the absence of ligand, sequestered in a large oligomeric heat-shock protein complex within target cells [15]. On binding ligand, however, the receptors undergo an activating conformational change that promotes the dissociation of inhibitory proteins [16]. This event permits the formation of receptor homodimers that are capable of interacting with specific high-affinity DNA-response elements located within the regulatory regions of target genes (Fig. 2) [17]. The DNA-bound receptor can then exert a positive or negative influence on target gene transcription.

FIGURE 2 The domain structures of the estrogen and progesterone receptors are similar.

In the classic models of steroid hormone action, it was proposed that progestins and estrogens function merely as switches that, on binding to their cognate receptor, permit conversion of the receptor in an all or nothing manner from an inactive to an active state [18]. This implied that ER and PR pharmacology was very simple, and that when corrected for affinity all progestins and estrogens were qualitatively the same. Furthermore, it suggested that antihormones (antagonists) function simply as competitive inhibitors of agonist binding, freezing the target receptor in an inactive state within the cell. Under most experimental conditions this simple model was sufficient to explain the observed biology of known PR and ER agonists and antagonists. However, systems were discovered that did not fit this simple model, indicating that the pharmacology of these receptor systems is more complex than originally believed. Studies probing the complex pharmacology of the antiestrogen tamoxifen have been very informative with respect to understanding the inadequacies of the classic model. Tamoxifen is widely used as a breast cancer chemotherapeutic and has been approved for use as a breast cancer chemopreventive in high-risk patients [19,20]. In ER-positive breast cancers, tamoxifen opposes the mitogenic action of estrogen(s) by binding to the receptor and competitively blocking agonist access. How-ever, it has become clear in recent years that tamoxifen is not a pure antagonist, because in some target organs it can exhibit estrogen-like activity. This is most apparent in both the skeletal system, where tamoxifen, like estrogen, increases lumbar spine bone mineral density, and the cardiovascular system, where both tamoxifen and estradiol have been shown to decrease low-density liproprotein (LDL) cholesterol [21,22]. These in vivo properties of tamoxifen led to its being reclassified as a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) rather than an antagonist. The observation that different ligand–receptor complexes were not recognized in the same manner in all cells was at odds with the established models of ER action. From a clinical perspective this was an important finding, because it suggested for the first time the possibility of developing compounds that, acting through their cognate receptor, could manifest different activities in different cells. From a molecular point of view, however, the observed pharmacology of tamoxifen begged a reevaluation of the classic model of ER action, and initiated the search for the cellular systems that enable ER–ligand complexes to manifest different biologies in different cells. These ongoing investigations have also provided significant insight into PR action, and have demonstra...