- 836 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin

About this book

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, often cited as 5-HT) is one of the major excitatory neurotransmitter, and the serotonergic system is one of the best studied and understood transmitter systems. It is crucially involved in the organization of virtually all behaviours and in the regulation of emotion and mood. Alterations in the serotonergic system, induced by e.g. learning or pathological processes, underlie behavioural plasticity and changes in mood, which can finally results in abnormal behaviour and psychiatric conditions. Not surprisingly, the serotonergic system and its functional components appear to be targets for a multitude of pharmacological treatments - examples of very successful drugs targeting the serotoninergic system include Prozac and Zoloft. The last decades of research have not only fundamentally expanded our view on serotonin but also revealed in much more detail an astonishing complexity of this system, which comprises a multitude of receptors and signalling pathways. A detailed view on its role in basal, but also complex, behaviours emerged, and, was presented in a number of single review articles. Although much is known now, the serotonergic system is still a fast growing field of research contributing to our present understanding of the brains function during normal and disturbed behaviour. This handbook aims towards a detailed and comprehensive overview over the many facets of behavioural serotonin research. As such, it will provide the most up to date and thorough reading concerning the serotonergic systems control of behaviour and mood in animals and humans. The goal is to create a systematic overview and first hand reference that can be used by students and scholars alike in the fields of genetics, anatomy, pharmacology, physiology, behavioural neuroscience, pathology, and psychiatry. The chapters in this book will be written by leading scientists in this field. Most of them have already written excellent reviews in their field of expertise. The book is divided in 4 sections. After an historical introduction, illustrating the growth of ideas about serotonin function in behaviour of the last forty years, section A will focus on the functional anatomy of the serotonergic system. Section B provides a review of the neurophysiology of the serotonergic system and its single components. In section C the involvement of serotonin in behavioural organization will be discussed in great detail, while section D deals with the role of serotonin in behavioural pathologies and psychiatric disorders.

- The first handbook broadly discussing the behavioral neurobiology of the serotonorgic transmitter system

- Co-edited by one of the pioneers and opinion leaders of the past decades, Barry Jacobs (Princeton), with an international list (10 countries) of highly regarded contributors providing over 50 chapters, and including the leaders in the field in number of articles and citations: K. P. Lesch, T. Sharp, A. Caspi, P. Blier, G.K. Aghajanian, E. C. Azmitia, and others

- The only integrated and complete resource on the market containing the best information integrating international research, providing a global perspective to an international community

- Of great value not only for researchers and experts, but also for students and clinicians as a background reference

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin by Christian P. Muller,Barry Jacobs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Neuroscience. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION 1

Functional Anatomy of the Serotonergic System

CHAPTER 1.1

Evolution of Serotonin: Sunlight to Suicide

Efrain C. Azmitia*

Department of Biology and Psychiatry, Center for Neuroscience, New York University, Washington Square East, New York

Abstract: Serotonin is involved in many of the behaviors and biological systems that are central to human life, extending from early developmental events related to neurogenesis and maturation, to apoptosis and neurodegeneration that underlie dementia and death. How can a single chemical be so powerful in determining the quality and quantity of human life? In this chapter, the evolution of serotonin and its biosynthetic pathways from tryptophan are examined. The essential components of the serotonin biosynthetic pathway are highly conserved. Tryptophan-based chemicals, including serotonin, melatonin and auxin, have important action in the differentiation, mitosis and survival of single cell organisms. As the complexity of life evolved into multicellular organisms, especially plants, serotonin levels rose dramatically. The importance of tryptophan, serotonin and auxin is evident in photosynthesis and plant growth. When the animal kingdom began, the ability to synthesize tryptophan was lost, and serotonin levels dropped accordingly. Animals had to develop many special mechanisms to secure tryptophan from their diets, and to carefully conserve its integrity during circulation throughout the body. There was the emergence of multiple receptors and reuptake proteins that permit serotonin actions without utilization of serotonin itself. Serotonin receptors appear as early as the blastula and gastrula stages of embryonic development, and continually monitor and regulate ontogenic changes as it serves phylogenic evolution.

The most amazing concept to emerge from an analysis of serotonin evolution is its relation to light. Beginning with the light-absorption properties of the indole ring of tryptophan, a direct path can be drawn to the effects of sunlight on photosynthesis and serotonin levels in plants. Progressing further in phylogeny, the effects of sunlight are seen on serotonin levels and on mood, sleep and suicide ideation in humans. The focus on the evolution of serotonin leads from an awareness of the beginning of life to the current human struggle to enjoy our dominant position on earth.

Keywords: seasonal affective disorder (SAD), tryptophan, auxin, hallucinogens, 5-HT1A receptor, photosynthesis, homeostasis indole, chloroplast, fungus, metazoa.

Introduction

It has always been an enigma how serotonin, a monoanmine neurotransmitter, can have such diverse and important functions in the human brain. The question is further complicated when it is recognized that serotonin exists in all the organs of the body (e.g., the skin, gut, lung, kidney, liver, and testis) and in nearly every living organism on Earth (e.g., fungi, plants, and animals) (Azmitia, 1999). Serotonin is phylogentically ancient, and evolved prior to the appearance of neurons. Whatever function serotonin has in the brain, it should be consistent with its evolutionary history. However, little attention has been given to the biological emergence of serotonin. Most neuroscience studies focus on serotonin in mediating particular behaviors (e.g., feeding, sex, sleep, and learning) or its involvement in specific brain disorders (e.g., depression, Alzheimer’s disease and autism). A broader view has been rarely raised. Over the past 50 years, several scientists have proposed general organistic roles for brain serotonin (Brodie and Shore, 1957; Woolley, 1961; Scheibel et al., 1975). A more comprehensive theory that includes expanded functions proposes that serotonin acts as a homeostatic regulator which integrates mind and body with the outside world (Azmitia, 2001, 2007). In reading this chapter, it is hoped that the reader will appreciate why serotonin came to be so important in the mental health of humans.

The evolution proposed for serotonin begins with a discussion of its precursor tryptophan and its metabolites in unicellular organisms nearly 3 billion years ago. To make serotonin from tryptophan, oxygen is needed, and in the earliest geological times the Earth’s atmosphere had little oxygen. Thus, serotonin is made specifically in unicellular systems capable of photosynthesis and the cellular production of oxygen. The conserved serotonin biosynthetic pathway began in the unicellular systems of cyanobacteria, green algae and fungi, and continually evolved to its current position in the human brain.

Table 1 Light spectrum of wavelengths that reach the Earth

Type | Wavelength (nm) |

Infrared | >1000 |

Red | 700–630 |

Orange | 630–590 |

Yellow | 590–560 |

Green | 560–490 |

Blue | 490–450 |

Violet | 450–400 |

UVA | 400–315 |

UVB | 315–380 |

UVC | 280–100 |

Photosynthesis is dependent on the energy derived from sunlight. The amount of light reaching Earth has seasonal variation and, because of the Earth’s tilting, is most noticeable at the polar extremes. Light can be roughly divided into ultraviolet (UV) and visible light (Table 1). In humans, UVB radiation produces sunburn and some forms of skin cancer, while UVA (black light) will produce skin discoloration and is necessary for vitamin D production. Glass and plastic can block UVB rays. The two types of light mainly absorbed during photosynthesis in plants are blue light and red light. The light most effective in alleviating the depression associated with seasonal affective disorder is blue light.

Tryptophan

Light capturing

Indole

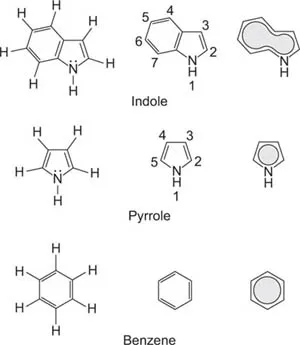

Indole is an organic compound consisting of a benzene ring and a pyrrole ring (Figure 1). The origin of the first photosynthetic pathway is proposed to be the photooxidation of uroporphyrinogen (a tetrapyrrole) by UVC, and this oxidation is accompanied by the release of molecular hydrogen. The oxidation of uroporphyrinogen to uroporphyrin, the first biogenetic porphyrin, could have occurred anaerobically and abiologically on the primordial Earth 3 billion years ago (Mercer-Smith et al., 1985). The indole structure can be found in many organic compounds, like the amino acid tryptophan, and in tryptophan-containing enzymes and receptors, alkaloids and pigments. The indole ring is electron rich and will lose an electron (oxidized) to an electrophilic compound, like a heavy metal, to decrease its oxidation number. The most reactive position on the indole structure for electrophilic aromatic substitution is C-3, which is 1013 times more reactive than benzene. Presently, cationic porphyrins are known to bind to the tryptophan moiety of proteins (Zhou et al., 2008). A similar situation to tryptophan occurs with chlorophyll, the light-capturing molecule of plants.

Figure 1 The indole structure consists of aromatic pyrrole and benzene rings. In the indole ring, the electrons are merged and a large pool of electrons becomes available for redox reactions.

Photosynthesis

Most proteins are endowed with an intrinsic UV fluorescence because they contain aromatic amino acids, particularly phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan. Comparing the three aromatic amino acids, tryptophan has the highest fluorescence quantum yield, overshadowing markedly the emissions of the other two. Generally, a distinction is made between tryptophan and non-tryptophan fluorescence. The tryptophan amino acid contains an indole backbone and absorbs light. Free tryptophan has characteristic fluorescence absorption at UVB (Borkman and Lerman, 1978; Lin and Sakmar, 1996), and the fluorescence emission is in the range of UVA-blue light (Du et al., 1998). This amino acid in proteins is needed for solar energy to drive photosynthesis in cyanobacteria, algae and plants (Vavilin et al., 1999). Solar energy conversion in photosynthesis involves electron transfer between an excited donor molecule and an acceptor molecule that are contained in the reaction center, an intrinsic membrane protein pigment complex (Wang et al., 2007). In the photosynthetic reaction centers of Rhodobacter sphaeroides, there are 39 tryptophan residues. Initiation of the electron transfer reaction by excitation results in a transient change in the absorbance at UVB, near the peak of the tryptophan absorbance band. According to Wang et al. (2007):

Given the similarity of the core features of the photosynthetic complexes from bacteria and plants, it is very likely that this same framework holds true for the initial electron transfer reaction of photosynthesis in general and possibly for other protein-mediated electron transfer reactions on similar time scales.

Absorption of blue light waves in chloroplasts leads to excitation of the indole structure of tryptophan so that it loses one of the electrons from its indole ring structure – it becomes oxidized. The electron that is lost from the indole ring passes through the intermediary of heavy metals to make its way down the electron chain. This process leads to the production of reducing cofactors such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), or reduction of H2O to O2. In bacterial ferric cytochrome P-450, the initial event of photoreduction is the photo-ionization of tryptophan in the active site of P-450 (Pierre et al., 1982). A laser flash at 265 nm, near the UVB range, triggers the nanosecond event of a protein structural change coincident with an ejection of electrons, and is followed by the photoreduction of the heme moiety (Bazin et al., 1982). The transfer of electrons between tryptophan and the heavy metals occurs at extremely rapid rates of several nanoseconds (Shih et al., 2008). This process takes place during photosynthesis, and is the procedure that converts solar energy into biological energy. CO2 and water are converted to O2 and glucose. This is the most important biochemical process on Earth. The Earth’s atmosphere contains 20 percent oxygen, and drives the biological evolution of aerobic organisms. Photosynthesis occurs in certain bacteria (e.g., cyanobacteria), algae (e.g., green algae) and all plants (Bryant and Frigaard, 2006).

Chloroplasts

Plants evolved a specialized intracellular organelle, the chloroplast, not only to capture light, but also as the source of tryptophan synthesis. This organelle may have evolved from captured cyanobacteria, and contains several hundred copies of chlorophyll. Chlorophyll became the universal transformer of solar energy in bioenergetics, and is sensitive to both blue and red light. In addition to its role in photosynthesis, blue light absorbance has been implicated as an early step in certain blue light-mediated morphogenic events (Rubinstein and Stern, 1991). The spectra for blue light-stimulated stomatal opening and phototropism are specialized for sensory transduction in the chloroplast (Quiñones et al., 1998). Thus blue light in plants not only underlies photosynthesis, it also produces morphological plasticity in the plant leaf to promote sensory transduction of light energy into bioenergy. Structural and functional advantages of the chlorophyll molecule may have determined its selection in evolution (Mauzerall, 1973). Chloroplast have a high need for tryptophan because of its light-absorption functions.

Amino acid

Tryptophan is the largest and most hydrophobic amino acid, and provides important folding signals to large proteins (Aoyagi et al., 2001). Tryptophan is the least used amino acid in the composition of protein molecules, generally comprising around 1-2 percent of the protein weight. In the basic genetic code, only one code is used for tryptophan, ‘UGG’, and this is flanked by stop codons on UAA, UAG, and UGA. Yet many important molecules are derived from tryptophan, including the nucleic acids adenosine and thymidine in DNA. Furthermore, a novel nucleolar protein, WDR55, carries a tryptophan–aspartate repeat motif and is involved in the production of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (Iwanami et al., 2008). These findings suggest that WDR55 is a nuclear modulator of rRNA synthesis, cell cycle progression, and embryonic organogenesis. Thus, despite its limited abundance, tryptophan and its associated molecules are involved in all cellular aspects of the organism’s life, and serve key regulatory roles in mitosis (Humphrey and Enoch, 1998), cell movement (Efimenko et al., 2006) and maturation (Cooke et al., 2002).

The synthesis of tryptophan takes several key enzymes: anthranilate synthase (EC 4.1.3.27), anthranilate phosphoribosyl-transferase (EC 2.4.2.18), anthranilate phosphoribosyl-isomerase (EC 5.3.1.24), indole-3-glycerol-phosphate synthase (EC 4.1.1.4) and tryptophan synthase (EC 4.2.1.20) (Figure 2). These enzymes are found in primitive unicellular organisms and in all plant systems. In many organisms there are isoforms of these that provide redundancy in tryptophan synthesis. In plants, tryptophan biosynthetic enzymes are synthesized as higher molecular weight precursors and then imported into chloroplasts and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Section 1: Functional Anatomy of the Serotonergic System

- Section 2: The Neurophysiology of Serotonin

- Section 3: Serotonin and Behavioral Control

- Section 4: Serotonin in Disease Conditions

- Index

- Color Plate