- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Global Regulatory Issues for the Cosmetics Industry

About this book

This volume examines regulatory issues of ingredients, manufacturing, and finished products, as well as claim substantiation, packaging, and advertising. A chapter on Chinese regulations will be one of the first about this country to be published in book form.• Includes a regulatory map of India and China • Global IP protection strategies • REACH and European Regulatory standards • "Green chemistry" in relation to cosmetics and regulation

- Simplifies global regulations for anyone exporting cosmetics

- Excellent reference not only for manufacturing and marketing, but for legal departments and packaging as well

- Describes how to develop a global regulatory strategy

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Regulatory Issues for the Cosmetics Industry by Karl Lintner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Fashion & Textile Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Green Chemistry: Foundations in Cosmetic Sciences

Amy S. Cannon 1 , John C. Warner 2

1 Beyond Benign, Woburn, MA, USA

2 Warner Babcock Institute for Green Chemistry, Woburn, MA, USA

1.1 Introduction

The manufacturing industries have been experiencing increasing pressure from regulatory and government agencies and society in general on issues concerning human health and the environment. While sustainability in its “big picture” ideals are easy for individuals to understand, it is at the practical level that clarity is less forthcoming. As corporations strive to meet various sustainability objectives within operations such as recycling and energy audits, fundamental incorporation at the most basic levels often do not exist. Sustainability should include every aspect of an industry's operations. Green chemistry speaks to the chemists and materials scientists to incorporate sustainable principles into their practices of creating products and developing processes. The field of green chemistry, since its beginnings in the early 1990s, has been growing in the scientific community at an ever-increasing rate. What began as a science around synthetic organic transformations has expanded to incorporate literally every aspect of chemistry, chemical engineering, and manufacturing sciences.

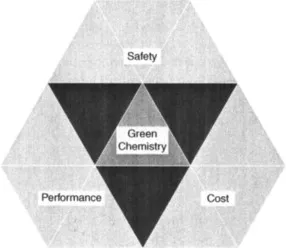

In the mid-1990s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began an awards program called the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards [1]. Each year five awards are given out to small and large businesses and academics for technologies that demonstrate the principles of green chemistry and that are also practical and can be commercialized. Green chemistry at its roots is about “real world” solutions to pollution prevention. For a technology to be successful in this awards program, and in fact to be considered “green chemistry,” it is not sufficient for the technology to be merely more benign than alternative technologies, it must also be viable in the marketplace. For a green chemistry technology to be viable in a competitive marketplace, it must satisfy two additional criteria in addition to product safety (Figure 1.1). It must demonstrate superior product performance; for example, environmentally benign cleaners that do not clean will not be desirable. It must also demonstrate appropriate economics. Society has demonstrated its unwillingness to pay a premium for environmentally benign technology. Adding these new criteria to product development is far from an easy task. Yet scientists in industry and academia have risen to the challenge and the more than 60 award winners of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Awards program are testament to the ingenuity and innovation being applied.

Figure 1.1 Three requirements for green chemistry technologies.

Interestingly, when one reviews a list of the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Award winners, one finds a scarcity of any technologies that could be classified as belonging wholly to the cosmetics and personal care industry. However, a review of the nomination packages shows that there are very few proposals being submitted from the cosmetics and personal care industry. This is not to say that some green chemistry is not already happening in this industry, but certainly there is a great deal of opportunity.

1.2 Green Chemistry

Green chemistry is a set of principles that speak to the design scientist at the earliest part of a product development program. It incorporates downstream implications at the fundamental molecular level. By anticipating potential problems around scale-up associated with regulatory and toxicological issues, it is possible to not only reduce costs from a variety of internalized and externalized sources but also streamline operations by increasing efficiency and time to market. These principles were published in 1998 in the book titled Green Chemistry Theory and Practice [2].

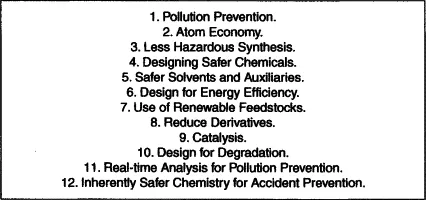

This book is a testament to the concerns of regulatory issues in the cosmetics and personal care industries. This chapter will discuss the twelve principles of green chemistry in the context of the cosmetics and personal care industries and how the concerns can be addressed at a fundamental level (Figure 1.2). While all the examples presented in this chapter may not be directly extracted from technologies immediately recognizable as being from this industry sector, it is hoped that they are similar enough to provide relative illustrative examples.

Figure 1.2 The twelve principles of green chemistry [2].

1.3 The Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry

Principle 1: Pollution Prevention. It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean up waste after it is formed.

The first principle is merely a technical restatement of the old adage “a pinch of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” It focuses on looking at the materials flow in a product life cycle, with an eye toward reducing waste before it is ever created, recognizing the costs associated with disposal, cleanup, and remediation. When one considers the ethical and economic implications of using hazardous materials, it becomes immediately obvious that a safer, nontoxic technology (with identical product performance and economics) will always be superior in the marketplace. The economics and product performance is only part of the story. One need only pick up a newspaper, turn on the radio, or watch television to witness the explosion of environmental consciousness in every aspect of society. The demands by consumers for “sustainable” products are only going to increase in the years to come.

Pollution prevention is best addressed by creating technologies and products that reduce waste at the very beginning stages of their life cycles. Countless examples are testament to this principle and many speak to the heart of the environmental movement. Environmental disasters are far too common in our history. And, the cleanup is unfortunately quite costly. In the United States, the EPA estimates that nearly $6.5 billion has been spent toward their brownfield initiative since its inception in 1995 [3]. It is estimated that the initiative involves nearly 450,000 brownfield sites throughout the United States. It is evident that it is better to have not created this waste rather than spend billions of dollars for cleanup after the fact.

Principle 2: Atom Economy. Synthetic methods should be designed to maximize the incorporation of all materials used in the process into the final product.

A typical product life cycle begins with the extraction of raw materials from the earth, followed by the functionalizing of the raw materials into useful feedstock chemicals that can be transformed into the various chemical products that we require for making products. The synthesis of the chemical products involves the use of various reagents in order to create the desired product. Many reagents are used to perform a specific function on the molecule, but are not actually incorporated into the product. The reagents that are not incorporated into the product typically result in waste in a chemical process.

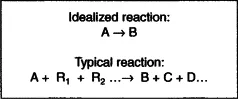

Throughout the history of chemistry, the quantitative success of a chemical transformation has typically focused on the concept of product yield. This number is based on the number of grams of products synthesized divided by the number of yields theoretically possible. While this measure provides some insight into the productivity of a chemical reaction, or series of reactions, much information is lost. Many synthetic transformations available in the chemist's toolbox do not merely follow the simple description of compound A is converted to compound B (Figure 1.3). More often than not, these transformations are far more complex with a number of reactants coming together to form a number of products (Figure 1.3). While the desired product may be obtained in high yield, it is possible and in fact often the case that along with the desired product an equivalent amount of some other anticipated by-product is formed.

Figure 1.3 An idealized versus a typical synthetic transformation. A: Starting material; B: Product; R: Reagent; C, D: Coproducts or by-products.

The atom economy of a reaction is based on a calculation developed by Barry Trost [4]: the ratio of the molecular weight of the atoms used to make a product divided by the molecular weight of all the reagents and starting materials used to make the product. It is a simple measure of the amount of waste created in a chemical process based on the atoms used in a process. This principle speaks to developing molecular transformations that incorporate a maximum number of atoms into the final product thus minimizing the atoms that appear as waste.

Principle 3: Less Hazardous Synthesis. Wherever practicable, synthetic methodologies should be designed to use and generate substances that possess little or no toxicity to human health and the environment.

It is often overlooked that the manufacturing pathway to synthesize a product ultimately may in fact go through a series of chemical intermediates.

This principle seeks to minimize the hazard associated with these intermediates. It is important to make the distinction that this principle is focused on materials that, in a perfect world, should not appear in the product. But, when considering worker exposure and the other associated costs related to disposal and hazardous materials, this is extremely important. Reducing the hazards associated with the way a product is made can drastically reduce worker liabilities and contribute toward worker health and safety.

In a typical manufacture of a product, the final step before packaging involves formulation. Formulation is the assembly of various materials acquired internally or from external vendors. It is important to recognize that these ingredient materials are being synthesized somewhere, whether in-house or by the supplier. Some solutions to working with hazardous materials can seem to be successful from the perspective of the formulator; it is in fact possible that somewhere upstream hazardous materials are being used and generated. In a complete life cycle analysis a “not-in-my-backyard” solution is not sufficient. Thus, it is important that the entire supply chain for a product be evaluated and optimized.

For example, an outside supplier typically supplies a plastic packaging material for most consumer products. There are several plastic types to choose from and they are often selected by their desired properties so as to contain the consumer product and retain its functionality. Many plastic materials are nontoxic to humans. However, the ways of manufacturing such plastic can be hazardous to the workers who operate and handle the materials during production. Therefore, it is important to reduce the hazard during the creation of such plastic materials.

One example where a plastic material was created that accomplished the task of reducing the hazard in a manufacturing setting is that of Cargill Dow's (now NatureWorks LLC) NatureWorks™ PLA process. In 2002, the company won the G...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Personal Care and Cosmetic Technology

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Green Chemistry: Foundations in Cosmetic Sciences

- Chapter 2: Reach—Life in and Outside the EU: How REACH Will Affect the Supply Chain

- Chapter 3: Cosmetic Ingredients: Definitions, Legal Requirements, and an Attempt to Harmonize (Global?) Characterization

- Chapter 4: “26 Allergens” in Cosmetics: A Challenge for All Stakeholders

- Chapter 5: Manufacturing Cosmetic Ingredients according to Good Manufacturing Practice Principles

- Chapter 6: Safe Cosmetics and Regulatory Compliance: From Burden to Opportunity (Cosmetics as Vectors for Bioterrorists?)

- Chapter 7: Cosmeceutical (Antiaging) Products: Advertising Rules and Claims Substantiation

- Chapter 8: Cosmetic Claim Substantiation: Methods and Legal Framework

- Chapter 9: The Impact of Global Regulations on Packaging

- Chapter 10: Global Cosmetic Regulations? A Long Way To Go …

- Chapter 11: Global Patent and Trade Mark Strategies: A Must for Everybody?

- Index