- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Principles of Soil and Plant Water Relations

About this book

Principles of Soil and Plant Water Relations combines biology and physics to show how water moves through the soil-plant-atmosphere continuum. This text explores the instrumentation and the methods used to measure the status of water in soil and plants. Principles are clearly presented with the aid of diagrams, anatomical figures, and images of instrumentation. The methods on instrumentation can be used by researchers, consultants, and the military to monitor soil degradation, including measurements of soil compaction, repellency, oxygen diffusion rate, and unsaturated hydraulic conductivity.Intended for graduate students in plant and soil science programs, this book also serves as a useful reference for agronomists, plant ecologists, and agricultural engineers.* Principles are presented in an easy-to-understand style* Heavily illustrated with more than 200 figures; diagrams are professionally drawn* Anatomical figures show root, stem, leaf, and stomata* Figures of instruments show how they work* Book is carefully referenced, giving sources for all information* Struggles and accomplishments of scientists who developed the theories are given in short biographies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction

Publisher Summary

I WHY STUDY SOIL-PLANT-WATER RELATIONS?

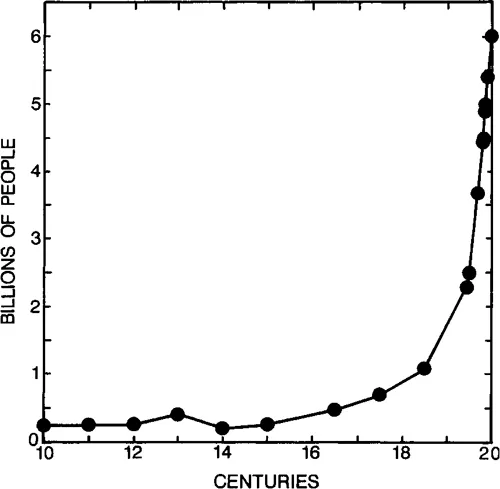

A Population

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Definitions of Physical Units and the International System

- Chapter 3: Structure and Properties of Water

- Chapter 4: Tensiometers

- Chapter 5: Soil-Water Terminology and Applications

- Chapter 6: Static Water in Soil

- Chapter 7: Water Movement in Saturated Soil

- Chapter 8: Field Capacity, Wilting Point, Available Water, and the Non-Limiting Water Range

- Chapter 9: Penetrometer Measurements

- Chapter 10: Measurement of Oxygen Diffusion Rate

- Chapter 11: Infiltration

- Chapter 12: Pore Volume

- Chapter 13: Time Domain Reflectometry to Measure Volumetric Soil Water Content

- Chapter 14: Root Anatomy and Poiseuille’s Law for Water Flow in Roots

- Chapter 15: Gardner’s Equation for Water Movement to Plant Roots

- Chapter 16: Measurement of Water Potential with Thermocouple Psychrometers

- Chapter 17: Measurement of Water Potential with Pressure Chambers

- Chapter 18: Stem Anatomy and Measurement of Osmotic Potential and Turgor Potential Using Pressure-Volume Curves

- Chapter 19: The Ascent of Water in Plants

- Chapter 20: Electrical Analogues for Water Movement through the Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Continuum

- Chapter 21: Leaf Anatomy and Leaf Elasticity

- Chapter 22: Stomata and Measurement of Stomatal Resistance

- Chapter 23: Solar Radiation, Black Bodies, Heat Budget, and Radiation Balance

- Chapter 24: Measurement of Canopy Temperature with Infrared Thermometers

- Chapter 25: Stress-Degree-Day Concept and Crop-Water-Stress Index

- Chapter 26: Potential Evapotranspiration

- Chapter 27: Water and Yield

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app