![]()

1

Overview

I. Scope of Insect Ecology

II. Ecosystem Ecology

A. Ecosystem Complexity

B. The Hierarchy of Subsystems

C. Regulation

III. Environmental Change and Disturbance

IV. Ecosystem Approach to Insect Ecology

V. Scope of This Book

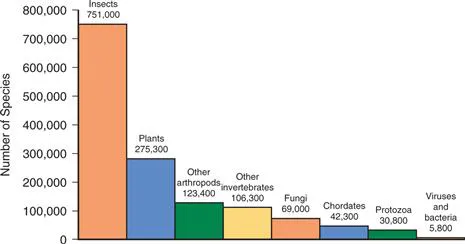

INSECTS ARE THE DOMINANT GROUP OF ORGANISMS ON EARTH, IN terms of both taxonomic diversity (>50% of all described species) and ecological function (E. Wilson 1992) (Fig. 1.1). Insects represent the vast majority of species in terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems and are important components of nearshore marine ecosystems as well. This diversity of insect species represents an equivalent variety of adaptations to variable environmental conditions. Insects affect other species (including humans) and ecosystem parameters in a variety of ways. The capacity for rapid response to environmental change makes insects useful indicators of change, major engineers and potential regulators of ecosystem conditions, and frequent competitors with human demands for ecosystem resources or vectors of human and animal diseases.

Fig. 1.1 Distribution of described species within major taxonomic groups. Species numbers for insects, bacteria, and fungi likely will increase greatly as these groups become better known. Data from E. O. Wilson (1992).

Insects also play critical roles in ecosystem function. They represent important food resources or disease vectors for many other organisms, including humans, and they have the capacity to alter rates and directions of energy and matter fluxes (e.g., as herbivores, pollinators, detritivores, and predators) in ways that potentially affect global processes. In some ecosystems, insects and other arthropods represent the dominant pathways of energy and matter flow, and their biomass may exceed that of the more conspicuous vertebrates (e.g., Whitford 1986). Some species are capable of removing virtually all vegetation from a site. They affect, and are affected by, environmental issues as diverse as ecosystem health, air and water quality, genetically modified crops, disease epidemiology, frequency and severity of fire and other disturbances, control of invasive exotic species, land use, and climate change. Environmental changes, especially those resulting from anthropogenic activities, affect abundances of many species in ways that alter ecosystem and, perhaps, global processes.

A primary challenge for insect ecologists is to place insect ecology in an ecosystem context that represents insect effects on ecosystem properties, as well as the diversity of their adaptations and responses to environmental conditions. Until relatively recently, insect ecologists have focused on the evolutionary significance of insect life histories and interactions with other species, especially as pollinators, herbivores, and predators (Price 1997). This focus has yielded much valuable information about the ecology of individual species and species associations and provides the basis for pest management or recovery of threatened and endangered species. However, relatively little attention has been given to the important role of insects as ecosystem engineers, other than to their effects on vegetation (especially commercial crop) or animal (especially human and livestock) dynamics.

Ecosystem ecology has advanced rapidly during the past 50 years. Major strides have been made in understanding how species interactions and environmental conditions affect rates of energy and nutrient fluxes in different types of ecosystems, how these provide free services (such as air and water filtration), and how environmental conditions both affect and reflect community structure (e.g., Costanza et al. 1997, Daily 1997, H. Odum 1996). Interpreting the responses of a diverse community to multiple interacting environmental factors in integrated ecosystems requires new approaches, such as multivariate statistical analysis and modeling (e.g., Gutierrez 1996, Liebhold et al. 1993, Marcot et al. 2001, Parton et al. 1993). Such approaches may involve loss of detail, such as combination of species into phylogenetic or functional groupings. However, an ecosystem approach provides a framework for integrating insect ecology with the changing patterns of ecosystem structure and function and for applying insect ecology to understanding of ecosystem, landscape, and global issues, such as climate change or sustainability of ecosystem resources. Unfortunately, few ecosystem studies have involved insect ecologists and, therefore, have tended to underrepresent insect responses and contributions to ecosystem changes.

I Scope of insect ecology

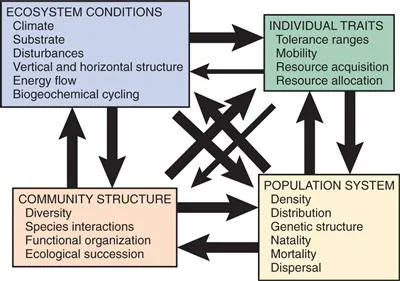

Insect ecology is the study of interactions between insects and their environment. Ecology is, by its nature, integrative, requiring the contributions of biologists, chemists, geologists, climatologists, soil scientists, geographers, mathematicians, and others to understand how the environment affects organisms, populations, and communities and is affected by their activities through a variety of feedback loops (Fig. 1.2). Insect ecology has both basic and applied goals. Basic goals are to understand and model these interactions and feedbacks (e.g., Price 1997). Applied goals are to evaluate the extent to which insect responses to environmental changes, including those resulting from anthropogenic activities, mitigate or exacerbate ecosystem change (e.g., Croft and Gutierrez 1991, Kogan 1998), especially in managed ecosystems.

Fig. 1.2 Diagrammatic representation of feedbacks between various levels of ecological organization. Size of arrows is proportional to strength of interaction. Note that individual traits have a declining direct effect on higher organizational levels but are affected strongly by feedback from all higher levels.

Research on insects and associated arthropods (e.g., spiders, mites, centipedes, millipedes, crustaceans) has been critical to development of the fundamental principles of ecology, such as evolution of social organization (Haldane 1932, Hamilton 1964, E. Wilson 1973); population dynamics (Coulson 1979, Morris 1969, Nicholson 1958, Varley and Gradwell 1970, Varley et al. 1973, Wellington et al. 1975); competition (Park 1948, 1954); predatorprey interaction (Nicholson and Bailey 1935); mutualism (Batra 1966, Bronstein 1998, Janzen 1966, Morgan 1968, Rickson 1971, 1977); island biogeography (Darlington 1943, MacArthur and Wilson 1967, Simberloff 1969, 1978); metapopulation ecology (Hanski 1989); and regulation of ecosystem processes, such as primary productivity, nutrient cycling, and succession (Mattson and Addy 1975, J. Moore et al. 1988, Schowalter 1981, Seastedt 1984). Insects and other arthropods are small and easily manipulated subjects. Their rapid numeric responses to environmental changes facilitate statistical discrimination of responses and make them particularly useful models for experimental study. Insects also have been recognized for their capacity to engineer ecosystem change, making them ecologically and economically important.

Insects fill a variety of important ecological (functional) roles. Many species are key pollinators. Pollinators and plants have adapted a variety of mechanisms for ensuring transfer of pollen, especially in tropical ecosystems where sparse distributions of many plant species require a high degree of pollinator fidelity to ensure pollination among conspecific plants (Feinsinger 1983). Other species are important agents for dispersal of plant seeds, fungal spores, bacteria, viruses, or other invertebrates (Moser 1985, Nault and Ammar 1989, Sallabanks and Courtney 1992). Herbivorous species are particularly well-known as agricultural and forestry “pests,” but their ecological roles are far more complex, often stimulating plant growth, affecting nutrient fluxes, or altering the rate and direction of ecological succession (MacMahon 1981, Maschinski and Whitham 1989, Mattson and Addy 1975, Schowalter and Lowman 1999, Schowalter et al. 1986, Trumble et al. 1993). Insects and associated arthropods are instrumental in processing of organic detritus in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and influence soil fertility and water quality (Kitchell et al. 1979, Seastedt and Crossley 1984). Woody litter decomposition usually is delayed until insects penetrate the bark barrier and inoculate the wood with saprophytic fungi and other microorganisms (Ausmus 1977, Dowding 1984, Swift 1977). Insects are important resources for a variety of fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, as well as for other invertebrate predators and parasites. In addition, some insects are important vectors of plant and animal diseases, including diseases such as malaria and plague, that have affected human and wildlife population dynamics.

The significant economic and medical or veterinary importance of many insect species is the reason for distinct entomology programs in various universities and government agencies. Damage to agricultural crops and transmission of human and livestock diseases has stimulated interest in, and support for, study of factors influencing abundance and effects of these insect species. Much of this research has focused on evolution of life history strategies, interaction with host plant chemistry, and predatorprey interactions as these contribute to our understanding of “pest” population dynamics, especially population regulation by biotic and abiotic factors. However, failure to understand these aspects of insect ecology within an ecosystem context undermines our ability to predict and manage insect populations and ecosystem resources effectively (Kogan 1998). Suppression efforts may be counterproductive to the extent that insect outbreaks represent ecosystem-level regulation of critical processes in some ecosystems.

II Ecosystem ecology

The ecosystem is a fundamental unit of ecological organization, although its boundaries are not easily defined. An ecosystem generally is considered to represent the integration of a more or less discrete community of organisms and the abiotic conditions at a site (Fig...