Social Anxiety

Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspectives

- 632 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Social Anxiety

Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspectives

About this book

Social Anxiety Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspectives, Second Edition, provides an interdisciplinary approach to understanding social anxiety disorder (SAD) by bringing together research across several disciplines, including social psychology, developmental psychology, behavior genetics, and clinical psychology. The book explains the different aspects of social anxiety and social phobia in adults and children, including the evolution of terminology and constructs, assessment procedures, relationship to personality disorders, and psychopathology. It considers most prominent theoretical perspectives on social anxiety and SAD discussed by social psychologists, developmental psychologists, behavior geneticists, clinical psychologists, and psychiatrists. These theoretical perspectives emphasize different factors that can contribute to the etiology and/or maintenance of social anxiety/SAD. Treatment approaches are also discussed, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, exposure intervention, social skills training. The contents of this volume represent some of the best views and thoughts in the field. It is hoped that the breadth of perspectives offered will help foster continued interdisciplinary dialogue and efforts toward cross-fertilization to advance the understanding, conceptualization, and treatment of chronic and debilitating social anxiety.- The most comprehensive source of up-to-date data, with review articles covering a thorough deliniation of social anxiety, theoretical perspectives, and treatment approaches- Consolidates broadly distributed literature into single source, saving researchers and clinicians time in obtaining and translating information and improving the level of further research and care they can provide- Each chapter is written by an expert in the topic area- Provides more fully vetted expert knowledge than any existing work- Integrates findings from various disciplines - clinical, social and developmental psychology, psychiatry, neuroscience, - rather than focusing on only one conceptual perspective- Provides the reader with more complete understanding of a complex phenomena, giving researchers and clinicians alike a better set of tool for furthering what we know- Offers coverage of essential topics on which competing books fail to focus, such as: related disorders of adult and childhood; the relationship to social competence, assertiveness and perfectionism; social skills deficit hypothesis; comparison between pharmacological and psychosocial treatments; and potential mediators of change in the treatment of social anxiety disorder population

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Introduction

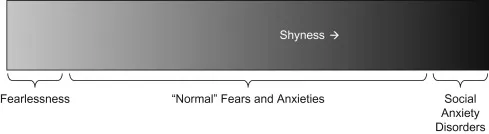

Overlapping and Contrasting Emotional States

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Introduction: Toward an Understanding of Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 1: Evolution of Terminology and Constructs in Social Anxiety and its Disorders

- Chapter 2: Assessment of Social Anxiety and Social Phobia

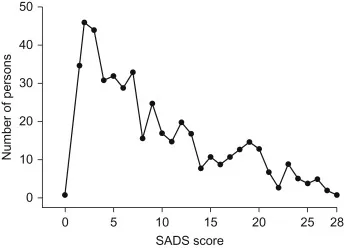

- Chapter 3: Shyness, Social Anxiety, and Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 4: Are Embarrassment and Social Anxiety Disorder Merely Distant Cousins, or Are They Closer Kin?

- Chapter 5: Social Anxiety Disorder and Its Relationship to Perfectionism

- Chapter 6: Social Phobia as a Deficit in Social Skills

- Chapter 7: Relation to Clinical Syndromes in Adulthood

- Chapter 8: Avoidant Personality Disorder and Its Relationship to Social Phobia

- Chapter 9: Social Anxiety in Children and Adolescents

- Chapter 10: Neuroendocrinology and Neuroimaging Studies of Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 11: Genetic Basis of Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 12: Temperamental Contributions to the Development of Psychological Profiles

- Chapter 13: Basic Behavioral Mechanisms and Processes in Social Anxieties and Social Anxiety Disorders

- Chapter 14: Cognitive Biases in Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 15: A Cognitive Behavioral Model of Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 16: Social Anxiety, Social Anxiety Disorder, and the Self

- Chapter 17: Social Anxiety, Positive Experiences, and Positive Events

- Chapter 18: Social Anxiety as an Early Warning System

- Chapter 19: Psychopharmacology for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 20: Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder

- Chapter 21: Comparison between Psychosocial and Pharmacological Treatments

- Chapter 22: Mechanisms of Action in the Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder

- Index