- 367 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environmental Physiology of Plants

About this book

This is the third edition of an established and successful university textbook. The original structure and philosophy of the book continue in this new edition, providing a genuine synthesis of modern ecological and physiological thinking, while entirely updating the detailed content. New features include a fresh, unified treatment of toxicity, emphasizing common features of plant response to ionic, gaseous, and other toxins, explicit treatment of issues relating to global change, and a section on the role of fire in plant physiology and communities. The illustrations in the text are improved over previous editions, including color plates for the first time, and the authors' continuing commitment to providing wide citation of the relevant literature has further improved the reference list. This revision of Environmental Physiology of Plants will ensure the reputation of this title as a useful and relevant text well into the 21st century.

- Includes enhanced illustrations, now with color plates

- Examines new molecular approaches which can be harnessed to solve problems in physiology

- Features new topics such as the unified treatment of toxicity, an explicit treatment of the issues relating to global change, and a section on the role of fire

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Environmental Physiology of Plants by Alastair H. Fitter,Robert K.M. Hay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Botany. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

1 Plant growth and development

This book is about how plants interact with their environment. In Chapter 2 to 4 we consider how they obtain the necessary resources for life (energy, CO2, water and minerals) and how they respond to variation in supply. The environment can, however, pose threats to plant function and survival by direct physical or chemical effects, without necessarily affecting the availability of resources; such factors, notably extremes of temperature and toxins, are the subjects of Chapters 5 and 6. Nevertheless, whether the constraint exerted by the environment is the shortage of a resource, the presence of a toxin, an extreme temperature, or even physical damage, plant responses usually take the form of changes in the rate and/or pattern of growth. Thus, environmental physiology is ultimately the study of plant growth, since growth is a synthesis of metabolic processes, including those affected by the environment. One of the major themes of this book is the ability of some successful species to secure a major share of the available resources as a consequence of rapid rates of growth (the concept of pre-emption or 'asymmetric competition'; Weiner, 1990).

When considering interactions with the environment, it is useful to discriminate between plant growth (increase in dry weight) and development (change in the size and/or number of cells or organs, thus incorporating natural senescence as a component of development). Increase in the size of organs (development) is normally associated with increase in dry weight (growth), but not exclusively; for example, the processes of cell division and expansion involved in seed germination consume rather than generate dry matter.

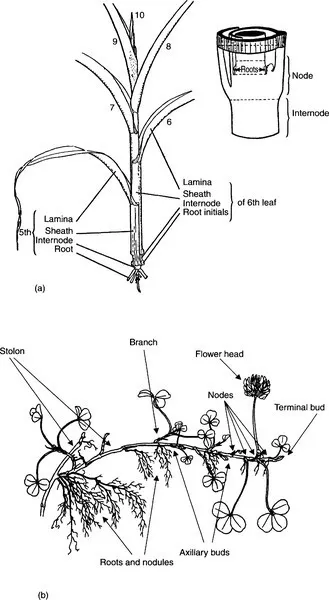

The pattern of development of plants is different from that of other organisms. In most animals, cell division proceeds simultaneously at many sites throughout the embryo, leading to the differentiation of numerous organs. In contrast, a germinating seed has only two localized areas of cell division, in meristems at the tips of the young shoot and root. In the early stages of development, virtually all cell division is confined to these meristems but, even in very short-lived annual plants, new meristems are initiated as development proceeds. For example, a root system may consist initially of a single main axis with an apical meristem but, in time, primary laterals will emerge, each with its own meristem. These can, in turn, give rise to further branches (e.g. Figs. 3.20, 3.22). Similarly, the shoots of herbaceous plants can be resolved into a set of modules, or phytomers, each comprising a node, an internode, a leaf and an axillary meristem (Fig. 1.1). Such branching patterns are common in nature (lungs, blood vessels, neurones, even river systems); in each case, the ‘daughters’ are copies of the parent branches from which they arose.

Figure 1.1 Two variations on the theme of modular construction, (a) Maize, where the module consists of a node, internode and leaf (encircling sheath and lamina; see inset diagram for spatial relationships). The axillary meristem normally develops only at one or two ear-bearing nodes, in contrast to many other grasses, whose basal nodes produce leafy branches (tillers). Nodal roots can form from the more basal nodes. Note that in the main diagram, the oldest modules (1–4) are too small to be represented at this scale, and the associated leaf tissues have been stripped away. (b) White clover stolon, where the module consists of a node, internode and vestigial leaf (stipule). The axillary meristems can generate stolon branches or shorter leafy or flowering shoots, and extensive nodal root systems can form (diagram kindly provided by Dr M. Fothergill) (adapted from Sharman, 1942)

The modular mode of construction of plants (Harper, 1986) has important consequences, including the generalization that development and growth are essentially indeterminate: the number of modules is not fixed at the outset, and a branching pattern does not proceed to an inevitable endpoint. Whereas all antelopes have four legs and two ears, a pine tree may carry an unlimited number of branches, needles or root tips (Plate 1). Plant development and growth are, therefore, very flexible, and capable of responding to environmental influences; for example, plants can add new modules to replace tissues destroyed by frost, wind or toxicity. On the other hand the potential for branching means that, in experimental work, particular care must be exercised in the sampling of plants growing in variable environments: adjacent pine trees of similar age can vary from less than 1 m to greater than 30 m in height, with associated differences in branching, according to soil depth and history of grazing (Plate 1). Such a modular pattern of construction, which is of fundamental importance in environmental physiology, can also pose problems in establishing individuality; thus, the vegetative reproduction of certain grasses can lead to extensive stands of physiologically-independent tillers of identical genotype.

Even though higher plants are uniformly modular, it is simple, for example, to distinguish an oak tree from a poplar, by the contrasting shapes of their canopies. Similarly, although an agricultural weed such as groundsel (Senecio vulgaris) can vary in size from a stunted single stem a few centimetres in height with a single flowerhead, to a luxuriant branching plant half a metre high with 200 heads, it will never be confused with a grass, rose or cactus plant. Clearly recognizable differences in form between species (owing to differences in the number, shape and three-dimensional arrangement of modules) reflect the operation of different rules governing development and growth, which have evolved in response to distinct selection pressures. For example, the phyllotaxis of a given species is a consistent character whatever the environmental conditions. The rules of ‘self assembly’ (the plant assembling itself, within the constraints of biomechanics, by reading its own genome or ‘blueprint’) are still poorly understood (e.g. Coen, 1999; Niklas, 2000).

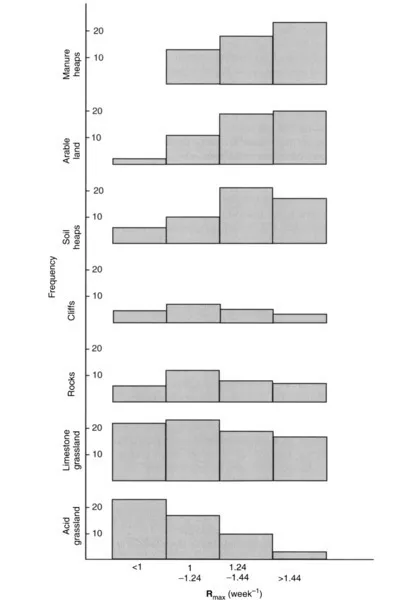

Where the environment offers abundant resources, few physical or chemical constraints on growth, and freedom from major disturbance, the dominant species will be those which can grow to the largest size, thereby obtaining the largest share of the resource cake by overshadowing leaf canopies and widely ramifying root systems – in simple terms, trees. Over large areas of the planet, trees are the natural growth form, but their life cycles are long and they are at a disadvantage in areas of intense human activity or other disturbance. Under such circumstances, herbaceous vegetation predominates, characterized by rapid growth rather than large size. Thus, not only size but also rate of growth are influenced by the favourability of the environment; where valid comparisons can be made among similar species, the fastest-growing plants are found in productive habitats, whereas unfavourable and toxic sites support slower-growing species (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Frequency distribution of maximum growth rate Rmax of species from a range of habitats varying in soil fertility and degree of stress. Frequencies do not add up to 100% because not all habitats are included. Manure heaps and arable land are the most fertile and disturbed of the habitats represented. (data from Grime and Hunt, 1975)

The assumption (Box 1) that the growth rate of a plant is in some way related to its mass, as is generally true for the early growth of annual plants, is dramatically confirmed by the growth of a population of the duckweed Lemna minor in a complete nutrient solution (Fig. 1.4). The assumption is, however, not tenable for perennials. For example, the trunk of an oak tree contributes to the welfare of the tree by supporting the leaf canopy in a dominant positi...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright page

- Preface to the Third Edition

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- 1: Introduction

- Part I: The Acquisition of Resources

- Part II: Responses to Environmental Stress

- References

- Name Index

- Species Index

- Subject Index