eBook - ePub

The Laboratory Computer

A Practical Guide for Physiologists and Neuroscientists

- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Laboratory Computer: A Practical Guide for Physiologists and Neuroscientists introduces the reader to both the basic principles and the actual practice of recording physiological signals using the computer.

It describes the basic operation of the computer, the types of transducers used to measure physical quantities such as temperature and pressure, how these signals are amplified and converted into digital form, and the mathematical analysis techniques that can then be applied. It is aimed at the physiologist or neuroscientist using modern computer data acquisition systems in the laboratory, providing both an understanding of how such systems work and a guide to their purchase and implementation.

- The key facts and concepts that are vital for the effective use of computer data acquisition systems

- A unique overview of the commonly available laboratory hardware and software, including both commercial and free software

- A practical guide to designing one's own or choosing commercial data acquisition hardware and software

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Laboratory Computer by John Dempster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Intelligence. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

The computer now plays a central role in the laboratory, as a means of acquiring experimental data, analysing that data, and controlling the progress of experiments. An understanding of it and the principles by which experimental data are digitised has become an essential part of the (ever lengthening) skill set of the researcher. This book provides an introduction to the principles and practical application of computer-based data acquisition systems in the physiological sciences. The aim here is to provide a coherent view of the methodology, drawing together material from disparate sources, usually found in highly compressed form in the methods sections of scientific papers, short technical articles, or in manufacturers’ product notes.

An emphasis is placed on both principles and practice. An understanding of the principles by which the physiological systems one is studying are measured is necessary to avoid error through the introduction of artefacts into the recorded data. A similar appreciation of the theoretical basis of any analysis methods employed is also required. Throughout the text, reference is therefore made to the key papers that underpin the development of measurement and analysis methodologies being discussed. At the same time, it is important to have concrete examples and to know, in purely practical terms, where such data acquisition hardware and software can be obtained, and what is involved in using it in the laboratory. The main commercially available hardware and software packages used in this field are therefore discussed along with their capabilties and limitations. In all cases, the supplier’s physical and website address is supplied. A significant amount of public domain, or ‘freeware’, software is also available and the reader’s attention is drawn to the role that this kind of software plays in research.

Physiology – the study of bodily function and particularly how the internal state is regulated – more than any other of the life sciences can be considered to be a study of signals. A physiological signal is the time-varying changes in some property of a physiological system, at the cellular, tissue or whole animal level. Many such signals are electrical in nature, cell membrane potential and current for instance, or chemical such as intracellular ion concentrations (H+, Ca++). But, almost any of the fundamental physical variables – temperature, force, pressure, light intensity – finds some physiological role. Records of such signals provide the raw material by which an understanding of body function is constructed, with advances in physiology often closely associated with improved measurement techniques. Physiologists, and particularly electrophysiologists, have always been ready to exploit new measurement and recording technology, and the computer-based data acquisition is no exception.

1.1 THE RISE OF THE LABORATORY COMPUTER

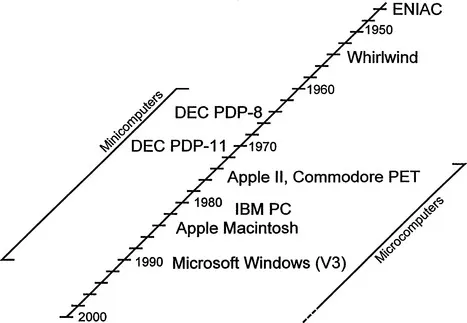

Computers first started to be used in the laboratory about 45 years ago, about 10 years after the first digital computer, the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Calculator), had gone into operation at the University of Pennsylvania. Initially, these machines were very large, room-size devices, seen exclusively as calculating machines. However, by the mid-1950s laboratory applications were becoming conceivable. Interestingly enough, the earliest of these applications was in the physiological (or at least psychophysiological) field. The Whirlwind system developed by Kenneth Olsen and others at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with primitive cathode ray tube (CRT) display systems, was used for studies into the visual perception of patterns associated with the air defence project that lay behind the funding of the computer (Green et al., 1959). The Whirlwind was of course still a huge device, powered by vacuum tubes, and reputed to dim the lights of Cambridge, Massachusetts when operated, but the basic principles of the modern laboratory computing could be discerned. It was a system controlled by the experimenter acquiring data in real time from an experimental subject and displaying results in a dynamic way.

Olsen went on to found Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) which pioneered the development of the minicomputer. Taking advantage of the developments in integrated circuit technology in the 1960s, minicomputers were much smaller and cheaper (although slower) than the mainframe computer of the time. While a mainframe, designed for maximum performance and storage capacity, occupied a large room and required specialised air conditioning and other support, a minicomputer took up little more space than a filing cabinet and could operate in the normal laboratory environment. Clark & Molnar (1964) describe the LINC (Laboratory INstrument Computer), a typical paper-tape-driven system of that time (magnetic disc drives were still the province of the mainframe). However, it could digitise experimental signals, generate stimuli, and display results on a CRT. The DEC PDP-8 (Programmable Data Processor) minicomputer was the first to go into widespread commercial production, and a variant of it the LINC-8 was designed specifically for laboratory use. The PDP-8 became a mainstay of laboratory computing throughout the 1960s, being replaced by the even more successful PDP-11 series in the 1970s.

Although the minicomputer made the use of a dedicated computer within the experimental laboratory feasible, it was still costly compared to conventional laboratory recording devices such as paper chart recorders. Consequently, applications were restricted to areas where a strong justification for their use could be made. One area where a case could be made was in the clinical field, and systems for the computer-based analysis of electrocardiograms and electroencephalograms began to appear (e.g. Stark et al., 1964). Electrophysiological research was another area where the rapid acquisition and analysis of signals could be seen to be beneficial. H.K. Hartline was one of the earliest to apply the computer to physiological experimentation, using it to record the frequency of nerve firing of Limulus (horseshoe crab) eye, in response to a variety of computer-generated light stimuli (see Schonfeld, 1964, for a review).

By the early 1980s most well-equipped electrophysiological laboratories could boast at least one minicomputer. Applications had arisen, such as the spectral analysis of ionic current fluctuations or the analysis of single ion channel currents, that could only be successfully handled using computer methods. Specialised software for these applications was being developed by a number of groups (e.g. D’Agrosa & Marlinghaus, 1975; Black et al., 1976; Colquhoun & Sigworth, 1995; Dempster, 1985; Re & Di Sarra, 1988). The utility of this kind of software was becoming widely recognised, but it was also becoming obvious that its production was difficult and time consuming. Because of this, software was often exchanged informally between laboratories which had existing links with the software developer or had been attracted by demonstrations at scientific meetings. Nevertheless, the cost of minicomputer technology right up to its obsolescence in the late 1980s prevented it from replacing the bulk of conventional laboratory recording devices.

Real change started to occur with the development of the microprocessor – a complete computer central processing unit on a single integrated circuit chip – by Intel Corp. in 1974. Again, like the minicomputer in its own day, although the first microprocessor-based computers were substantially slower than the contemporary minicomputers, their order-of-magnitude lower cost opened up a host of new opportunities for their use. New companies appeared to exploit the new technology, and computers such as the Apple II and the Commodore PET began to appear in the laboratory (examples of their use can be found in Kerkut, 1985; or Mize, 1985). Not only that; computers had become affordable to individuals for the first time, and they began to appear in the home and small office. The era of the personal computer had begun.

As integrated circuit technology improved it became possible to cram more and more transistors on to each silicon chip. Over the past 25 years this has led to a constant improvement in computing power and reduction in cost. Initially, each new personal computer was based on a different design. Software written for one computer could not be expected to run on another. As the industry matured, standardisation began to be introduced, first with the CP/M operating system and then with the development of the IBM (International Business Machines) Personal Computer in 1981. IBM being the world’s largest computer manufacturer at the time, the IBM PC became a de facto standard, with many other manufacturers copying its design and producing IBM PC-compatible computers or ‘clones’. Equally important was the appearance of the Apple Macintosh in 1984, the first widely available computer with a graphical user interface (GUI), which used the mouse as a pointing device. Until the introduction of the Macintosh, using a computer involved the user in learning its operating system command language, a significant disincentive to many. The Macintosh, on the other hand, could be operated by selecting options from a series of menus using its mouse or directly manipulating ‘icons’ representing computer programs and data files on the screen. Thus while the microprocessor made the personal computer affordable to all, the graphical user interface made it usable by all. By the 1990s, the GUI paradigm for operating a computer had become near universal, having been adopted on the IBM PC family of computers, in the form of Microsoft’s Windows operating system. Figure 1.1 summarises these developments.

Figure 1.1 Laboratory computers over the past 50 years.

The last decade has seen ever-broadening application of the personal computer, not simply in the laboratory, but in society in general, in the office and in the home. The standardisation of computer systems has also shifted power away from the hardware to software manufacturers. The influence of hardware suppliers such as IBM and DEC, who dominated the market in the 1970s and 80s, has waned, to be replaced by the software supplier Microsoft, which supplies the operating systems for 90% of all computers. Currently, the IBM PC family dominates the computer market, with over 90% of systems running one of Microsoft’s Windows operating systems. Apple, although with a much lesser share of the market (9%), still plays a significant role, particularly in terms of innovation. The Apple Macintosh remains a popular choice as a laboratory computer in a number of fields, notably molecular biology.

Most significantly from the perspective of laboratory computer, the computer has now become the standard means for recording and analysing experimental data. The falling cost of microprocessor-based digital technology has continued to such an extent that it is now usually the most cost-effective means of recording experimental signals. Conventional analogue recording devices with mechanical components, paper chart recorders for instance, have always required specialist high-precision engineering. Digital technology, on the other hand, can be readily mass-produced, once initial design problems have been solved. When this is combined with the measurement and analysis capabilities that the computer provides, the case for using digital technology becomes almost unassailable. Thus while we will no doubt see conventional instrumentation in the laboratory for a long time to come, as such devices wear out, their replacements are likely to be digital in nature.

Since the computer lies at the heart of the data acquisition system, an appreciation of the key factors that affect its performance is important. Chapter 2 (The Personal Computer) therefore covers the basic principles of computer operation and the key hardware and software features in the modern personal computer. The three main computer families in common use in the laboratory – IBM PC, Apple Macintosh, Sun Microsystems or Silicon Graphic International workstations – are compared, along with the respective operating system software necessary to use them. The capabilities of various fixed and removable disc storage technologies are compared, in terms of capacity, rate of data transfer and suitability as a means of long-term archival storage.

1.2 THE DATA ACQUISITION SYSTEM

There are four key components to a computer-based data acquisition system that need to be considered:

• Transducer(s)

• Signal conditioning

• Data storage sys...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- BIOLOGICAL TECHNIQUES

- Copyright

- Series Preface

- Preface

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: The Personal Computer

- Chapter 3: Digital Data Acquisition

- Chapter 4: Signal Conditioning

- Chapter 5: Transducers and Sensors

- Chapter 6: Signal Analysis and Measurement

- Chapter 7: Recording and Analysis of Intracellular Electrophysiological Signals

- Chapter 8: Recording and Analysis of Extracellular Electrophysiological Signals

- Chapter 9: Image Analysis

- Chapter 10: Software Development

- References

- Suppliers

- Index