eBook - ePub

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy

- 454 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy

About this book

Laser induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) is basically an emission spectroscopy technique where atoms and ions are primarily formed in their excited states as a result of interaction between a tightly focused laser beam and the material sample. The interaction between matter and high-density photons generates a plasma plume, which evolves with time and may eventually acquire thermodynamic equilibrium. One of the important features of this technique is that it does not require any sample preparation, unlike conventional spectroscopic analytical techniques. Samples in the form of solids, liquids, gels, gases, plasmas and biological materials (like teeth, leaf or blood) can be studied with almost equal ease. LIBS has rapidly developed into a major analytical technology with the capability of detecting all chemical elements in a sample, of real- time response, and of close-contact or stand-off analysis of targets. The present book has been written by active specialists in this field, it includes the basic principles, the latest developments in instrumentation and the applications of LIBS . It will be useful to analytical chemists and spectroscopists as an important source of information and also to graduate students and researchers engaged in the fields of combustion, environmental science, and planetary and space exploration.* Recent research work* Possible future applications* LIBS Principles

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

BASIC PHYSICS AND INSTRUMENTATION

Chapter 1 Fundamentals of Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy

Chapter 2 Atomic Emission Spectroscopy

Chapter 3 Laser Ablation

Chapter 4 Physics of Plasma in Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy

Chapter 5 Instrumentation for Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy

Chapter 1

Fundamentals of Laser Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy

aLaser and Spectroscopy Laboratory, Department of Physics, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005, INDIA

bInstitute for Clean Energy Technology, Mississippi State University Mississippi State, U.S.A

1. INTRODUCTION

The devastating power of the laser was demonstrated soon after its invention when a focused laser beam produced a bright flash in air similar to the spark produced by lightening discharge between two clouds [1]. Another spectacular effect involved the production of luminous clouds of vaporized material blasted from a metallic surface and often accompanied by a shower of sparks when the laser was focused on a metal surface [2,3]. These laser effects have found many technological applications in the fields of metalworking, plasma production, and semiconductors. When a pulsed laser beam of high intensity is focused, it generates plasma from the material. This phenomenon has opened up applications in many fields of science from thin film deposition to elemental analysis of samples. The possibility of using a high-power, short-duration laser pulse to produce a high temperature, high-density plasma was pointed out by Basov and Krokhin [4] as a means of filling a fusion device by vaporizing a small amount of material. Laser ablation of solids into background gases is now a proven method of cluster-assembly [5,6]. In this method, a solid target is vaporized by a powerful laser pulse to form partially ionized plasma that contains atoms and small molecules. Not much is known about the formation and transport of particles in laser ablation plumes. In recent years there has been notable interest both in an increased understanding of laser induced plasmas (LIP) and in the development of their applications. Emission spectroscopy is used for elemental analysis of targets from which the luminous plasma is generated and it can also be applied to determine the temperature, electron density and atom density in the LIP [7].

The history of laser spark spectroscopy runs parallel to the development of highpower lasers, starting with the early use of a ruby laser for producing sparks in gases [8]. In subsequent years the spectral analysis of LIP became an area of study that has significantly matured at present. The current developments of this technique for chemical analysis can be traced to the work of Radziemski and Cremers [9] and their co-workers at Los Alamos National Laboratory in the 1980s. It was this research group that first coined the acronym LIBS for laser induced breakdown spectroscopy. During the last two decades, LIBS has undergone a dramatic transformation in terms of hardware, software and application areas. It has become a powerful sensor technology for both laboratory and field use. In order to obtain a reliable quantitative elemental analysis of a sample using LIBS, one needs to control several parameters that can strongly affect the measurements. Some of these parameters are the laser wavelength, its irradiance, the morphology of the sample surface, the amount of ablated and vaporized sample, and the ability of the resulting plasma to absorb the optical energy. If these and related parameters are properly optimized, the spectral line intensities will be proportional to the elemental concentration. In the following sections we briefly describe the basic components and the underlying physical processes that are essential to appreciate the range of applications and power of LIBS.

2. LASERS FOR LIBS

The main properties of laser light which distinguish it from conventional light sources are the intensity, directionality, monochromaticity, and coherence. In addition the laser may operate to emit radiation continuously or it may generate radiation in short pulses. Some lasers can generate radiation with the above mentioned properties and that is tunable over a wide range of wavelengths. Generally pulsed lasers are used in the production of plasmas and also in laser induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS). We consider only those properties of lasers relevant to plasma production in gaseous, liquid and solid samples so that the role of various types of laser systems used in LIBS experiments is clearly understood in the later chapters of this book. It is possible to generate short-duration laser pulses with wavelengths ranging from the infrared to the ultraviolet, with powers of the order of millions of watts. Several billions to trillions of watts and more have been obtained in a pulse from more sophisticated lasers. Such high-power pulses of laser radiation can vaporize metallic and refractory surfaces in a fraction of a second. It is to be noted that not only the peak power of the laser, but also the ability to deliver the energy to a specific location is of great importance. For LIBS, the power per unit area that can be delivered to the target is more important than the absolute value of the laser power. The power per unit area in the laser beam is termed “irradiance” and is also called “flux” or “flux density.” Conventional light sources with kilowatts powers cannot be focused as well as laser radiation and therefore are not capable of producing effects that lasers can.

The next property of laser radiation that is of interest is the directionality of the beam. Laser radiation is confined to a narrow cone of angles which is of the order of a few tenths of a milliradian for gas lasers to a few milliradians for solid state lasers. Because of the narrow divergence angle of laser radiation, it is easy to collect all the radiation with a simple lens. The narrow beam angle also allows focusing of the laser light to a small spot. Therefore the directionality of the beam is an important factor in the ability of lasers to deliver high irradiance to a target. Coherence of the laser is also related to the narrowness of the beam divergence angle and it is indirectly related to the ability of the laser to produce high irradiance. However, coherence is not of primary concern in LIBS. Provided that a certain number of watts per square centimeter are delivered to a surface, the effect will be much the same whether the radiation is coherent or not. The monochromaticity of the laser as such plays very little role as far as plasma production is concerned because it is the power per unit area on the target that matters irrespective of the fact whether the radiation is monochromatic or covers a broad band. In special cases, one may require highly monochromatic laser radiation to probe the plasma using resonance excitation of atomic species. The frequency spread of gas lasers is of the order of one part in 1010 or even better and for solid lasers, it is of the order of several megahertz. In specifying the frequency spread, we have taken the width of a single cavity mode of the laser, although most lasers operate in more than one cavity mode so that the total frequency spread may cover the entire line width of the laser transition. The frequency spread of each of the cavity modes is much narrower than the line width of the laser transition and the former is used to characterize the frequency stability of the laser.

2.1. Mode Properties of Lasers

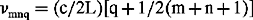

The optical cavity of a laser is determined by the configuration of the two end mirrors. The stationary patterns of the electromagnetic waves formed in the cavity are called modes. For a cavity formed by two confocal spherical mirrors separated by a distance L, the frequency ν of a mode (mnq) is given by

where c is the velocity of light, q is a large integer, and m and n are small integers. The axial modes correspond to m = n = 0 and involve a standing wave pattern with an integral number q of half wavelengths with q λ/2 = L, between the two mirrors with a node at each mirror. The separation between frequencies of two consecutive axial modes (c/2L) is of the order of gigahertz for typical solid state lasers. The transverse modes of the laser are designated by TEMmn. They affect the focusing properties of the laser beam. The smallest focal spots and highest irradiance is obtained with beams containing the lowest transverse modes with the smallest pair of values m, n. The higher transverse modes have radial intensity distributions which are less and less concentrated along the resonator axis with increasing values of m or n. These modes are also known as off-axis modes and their diffraction losses are much higher than that of the fundamental modes TEM00q. Some of the patterns for transver...

Table of contents

- Cover Image

- Table of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contributors

- Acronyms

- PART I. BASIC PHYSICS AND INSTRUMENTATION

- PART II. NEW LIBS TECHNIQUES

- Part III. LIBS APPLICATIONS

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy by Jagdish P. Singh,Surya N. Thakur,Surya Narayan Thakur in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.