eBook - ePub

Hierarchical Modeling and Inference in Ecology

The Analysis of Data from Populations, Metapopulations and Communities

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hierarchical Modeling and Inference in Ecology

The Analysis of Data from Populations, Metapopulations and Communities

About this book

A guide to data collection, modeling and inference strategies for biological survey data using Bayesian and classical statistical methods.This book describes a general and flexible framework for modeling and inference in ecological systems based on hierarchical models, with a strict focus on the use of probability models and parametric inference. Hierarchical models represent a paradigm shift in the application of statistics to ecological inference problems because they combine explicit models of ecological system structure or dynamics with models of how ecological systems are observed. The principles of hierarchical modeling are developed and applied to problems in population, metapopulation, community, and metacommunity systems. The book provides the first synthetic treatment of many recent methodological advances in ecological modeling and unifies disparate methods and procedures.The authors apply principles of hierarchical modeling to ecological problems, including * occurrence or occupancy models for estimating species distribution* abundance models based on many sampling protocols, including distance sampling* capture-recapture models with individual effects* spatial capture-recapture models based on camera trapping and related methods* population and metapopulation dynamic models* models of biodiversity, community structure and dynamics

- Wide variety of examples involving many taxa (birds, amphibians, mammals, insects, plants)

- Development of classical, likelihood-based procedures for inference, as well as Bayesian methods of analysis

- Detailed explanations describing the implementation of hierarchical models using freely available software such as R and WinBUGS

- Computing support in technical appendices in an online companion web site

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hierarchical Modeling and Inference in Ecology by J. Andrew Royle,Robert M. Dorazio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 CONCEPTUAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN ECOLOGY AND STATISTICS

A bird in the hand

is worth two in the bush ….

…. if p = 0.5

Much of contemporary ecological theory, conservation biology, and natural resource management is concerned with variation in the abundance or occurrence of species. Variation may exist over space or time and is often associated with measurable differences in environmental characteristics. Indeed, ecology has been defined as the study of spatial and temporal variation in abundance and distribution of species (Krebs, 2001). In this regard, a variety of problems in ecology require inferences about species abundance or occurrence. Examples include estimation of population size (or density), assessment of species’ range and distribution, and identification of landscape-level characteristics that influence occurrence or abundance. Other examples include studies of processes that affect the dynamics of populations, metapopulations, or communities (i.e., survival, recruitment, dispersal, and interactions among species or individuals).

A common problem in the study of populations or communities is that a census (i.e., complete enumeration) of individuals is rarely attainable, given the size of the region that must be surveyed. Consequently, conclusions about populations or communities must be inferred from samples. An additional complication is that individuals exposed to sampling may not be detected. Detection problems are especially acute in surveys of animals in which detection failures can be produced by a variety of sources (e.g., differences in behavior or coloration of individuals, differences in observers’ abilities, etc.). In response to these problems, clever sampling protocols and statistical methods of analysis are commonly used in surveys of animal populations. These protocols and analytical methods, whose origins may be traced to the efforts of Dahl (1919), Lincoln (1930) and Leopold (1933) (also see discussions by Hayne (1949) and Le Cren (1965)), include capture–recapture sampling (Cormack, 1964; Jolly, 1965; Seber, 1965), distance sampling (Burnham and Anderson, 1976), and the statistical methods for analyzing such data. One of the first major syntheses of these early efforts is provided by Seber (1982). Updates of his synthesis are still regarded as general references for sampling and inference in animal populations (Seber, 1992; Schwarz and Seber, 1999). A number of books have also been published recently on the subjects of sampling biological populations and statistical modeling and inference in ecology (Borchers et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2002; Gotelli and Ellison, 2004; Buckland et al., 2004b; MacKenzie et al., 2006; Clark and Gelfand, 2006). In addition to these syntheses, countless monographs and review articles on the same topics have appeared in the primary literature.

In the face of this recent proliferation, what more can we possibly offer? We offer a comprehensive treatment of modeling strategies for many different classes of ecological inference problems, ranging from classical populations of individuals to spatially organized community systems (metacommunities). However, our primary conceptual contribution is the development of a principled approach to modeling and inference in ecological systems based on hierarchical models. We adopt a strict focus on the use of parametric inference and probability modeling, which yields a cohesive and generic approach for solving a large variety of problems in population, metapopulation, community and metacommunity systems. Hierarchical models allow an explicit and formal representation of the data into constituent models of the observations and of the underlying ecological or state process. The model of the ecological process of interest (the ‘process model’) describes variation (spatial, temporal, etc.) in the ecological process that is the primary object of inference. This process is manifest in a state variable, which is typically unobservable (or partially so). An example would be animal abundance or occurrence at some point in space and time. In contrast, the model of the observations (the ‘observation model’) contains a probabilistic description of the mechanisms that produce the observable data. In ecology, this often involves an explicit characterization of detection bias.

1.1 SCIENCE BY HIERARCHICAL MODELING

This description of models by explicit observation and state process components is now a fairly conventional approach to statistical modeling in ecology, where the term ‘state-space’ model is widely used. In fact, the term state-space might be more common in the prevailing ecological literature. Some recent examples include De De Valpine and Hastings (2002), Buckland et al. (2004a), Jonsen et al. (2005), Viljugrein et al. (2005), Newman et al. (2006), and Dennis et al. (2006). Our view of hierarchical modeling is that it is not merely a technical approach to model formulation, or a method of variance accounting. Rather, hierarchical modeling is a much broader conceptual framework for doing science. By focusing our thinking on conceptually and scientifically distinct components of a system, it helps clarify the nature of the inference problem in a mathematically and statistically precise way. Thus, while hierarchical models yield a cohesive treatment of many technical issues (components of variance, combining sources of data, ‘scale’), they also foster the fundamental (to science) activities of ‘model building’ and inference. Our colleague L. Mark Berliner advocates this view in application of hierarchical models to geophysical problems. For this reason he has, on several occasions, made a distinction between scientific modeling – based on hierarchical models in which the underlying physical or biological process is manifest as one component of the model – and statistical modeling, in which this distinction is not made explicitly. The conceptual and practical distinction between these two approaches provides, in large part, the motivation for and content of this book.

Many of the practical benefits of hierarchical modeling are technical – accounting for sources of variance, different kinds of data, ‘scales’ of observation and many other factors. But the conceptual benefits of hierarchical modeling are both profound and profoundly subtle, and we elucidate and develop supporting arguments for this view in the following chapters of this book, using many classes of models that are widely used in ecology. For example, in Chapter 3 we discuss what is probably the simplest but most widely used class of statistical models in ecology – models for ‘occurrence’ which are commonly formulated in terms of simple logistic regression. We demonstrate in several subsequent chapters how relatively simple hierarchical models for occurrence provide solutions to problems of fundamental importance in ecology. In Chapter 4, we discuss models of ‘occupancy and abundance.’ The linkage between occupancy and abundance is expressed naturally using a hierarchical model. In Chapter 12, we show how models of animal community structure are formulated naturally as ‘multi-species’ models of occurrence. We provide many more examples in other chapters.

1.1.1 Example: Modeling Replicated Counts

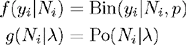

We focus briefly on a particular example (which is described in some generality in Chapter 8) that provides an insightful illustration of the profound subtlety alluded to above. This interesting hierarchical model arises in the context of spatially-indexed sampling of a species. Suppose Ni is the (unobserved) ‘local abundance’ or population size of individuals on spatial sample unit i = 1, 2,…, M. Suppose further that yi is the observed count of individuals at sample unit i. A common model for such data is to assume (or assert) that individuals within the population are sampled independently of one another, in which case yi is binomial with index Ni and parameter p (commonly interpreted as detection probability). In this case, the Ni ‘parameters’ are unobserved. As such, it would be natural in many settings to impose a model on them (e.g., thinking of them as random effects). For example, we might suppose that the local abundance parameters are realizations of Poisson random variables, with parameter λ. We have in this case a two-stage hierarchical model composed of a binomial observation model and a Poisson ‘process’ model, which we denote in compact notation as follows:

This is a degenerate hierarchical model in the sense that parameters are confounded – that is, the marginal distribution of y is Poisson with mean pλ, and unique estimates of p and λ cannot be obtained – but it seems like a sensible construction of an ecological sampling problem when sample units are spatially referenced and counts of organisms are obtained on each sample unit. (See Section 8.3 for an application of this model.)

The degeneracy of the model is easily resolved by adding a little bit more information in the form of replicate counts. That is, suppose each local population is sampled J = 2 times, yielding counts yij which we assume, as before, are Bin(Ni, p) outcomes. In this case, the hierarchical model is not degener...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: CONCEPTUAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN ECOLOGY AND STATISTICS

- Chapter 2: ESSENTIALS OF STATISTICAL INFERENCE

- Chapter 3: MODELING OCCUPANCY AND OCCURRENCE PROBABILITY

- Chapter 4: OCCUPANCY AND ABUNDANCE

- Chapter 5: INFERENCE IN CLOSED POPULATIONS

- Chapter 6: MODELS WITH INDIVIDUAL EFFECTS

- Chapter 7: SPATIAL CAPTURE–RECAPTURE MODELS

- Chapter 8: METAPOPULATION MODELS OF ABUNDANCE

- Chapter 9: OCCUPANCY DYNAMICS

- Chapter 10: MODELING POPULATION DYNAMICS

- Chapter 11: MODELING SURVIVAL

- Chapter 12: MODELS OF COMMUNITY COMPOSITION AND DYNAMICS

- Chapter 13: LOOKING BACK AND AHEAD

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX