- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From neighborhoods as large as Chelsea or the Castro, to locales limited to a single club, like The Shamrock in Madison or Sidewinders in Albuquerque, gay areas are becoming normal. Straight people flood in. Gay people flee out. Scholars call this transformation assimilation, and some argue that we—gay and straight alike—are becoming "post-gay." Jason Orne argues that rather than post-gay, America is becoming "post-queer," losing the radical lessons of sex.

In Boystown, Orne takes readers on a detailed, lively journey through Chicago's Boystown, which serves as a model for gayborhoods around the country. The neighborhood, he argues, has become an entertainment district—a gay Disneyland—where people get lost in the magic of the night and where straight white women can "go on safari." In their original form, though, gayborhoods like this one don't celebrate differences; they create them. By fostering a space outside the mainstream, gay spaces allow people to develop an alternative culture—a queer culture that celebrates sex.

Orne spent three years doing fieldwork in Boystown, searching for ways to ask new questions about the connective power of sex and about what it means to be not just gay, but queer. The result is the striking Boystown, illustrated throughout with street photography by Dylan Stuckey. In the dark backrooms of raunchy clubs where bachelorettes wouldn't dare tread, people are hooking up and forging "naked intimacy." Orne is your tour guide to the real Boystown, then, where sex functions as a vital center and an antidote to assimilation.

In Boystown, Orne takes readers on a detailed, lively journey through Chicago's Boystown, which serves as a model for gayborhoods around the country. The neighborhood, he argues, has become an entertainment district—a gay Disneyland—where people get lost in the magic of the night and where straight white women can "go on safari." In their original form, though, gayborhoods like this one don't celebrate differences; they create them. By fostering a space outside the mainstream, gay spaces allow people to develop an alternative culture—a queer culture that celebrates sex.

Orne spent three years doing fieldwork in Boystown, searching for ways to ask new questions about the connective power of sex and about what it means to be not just gay, but queer. The result is the striking Boystown, illustrated throughout with street photography by Dylan Stuckey. In the dark backrooms of raunchy clubs where bachelorettes wouldn't dare tread, people are hooking up and forging "naked intimacy." Orne is your tour guide to the real Boystown, then, where sex functions as a vital center and an antidote to assimilation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Boystown by Jason Orne,Jay Orne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & LGBT Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2017Print ISBN

9780226413396, 9780226413259eBook ISBN

97802264134261

Nightfall

The crush of people standing in the hallway just within view of the stage delineated the boundary between the front and back bars at Cocktail on Saturday nights. At five foot six, I’m a smaller man. I can squeeze through crowds more easily, so I stood in front pushing sideways, pulling Austin along with me by the hand. The three-foot-long tables lined up perpendicular to the western wall took up valuable real estate for spectators at this hour, leaving us on the edge of the ring of empty space surrounding the stripper’s stage.

“Oh, it’s Peoria,” Austin, my then-boyfriend, now-husband, nudged me to look over to our left, where three middle-aged, straight, white women stood, talking excitedly to their white, gay, male coworker who had brought them down from the suburbs for a fun night out on the town—I’m an eavesdropper.

“Ooh, that’s mean,” I said. “I’m calling you out on that.” I pulled out my phone to take a few notes on the scene.

To our right, a middle-aged Latino man in a long, yellow polo shirt, stylish black-framed glasses, and the gelled Caesar haircut I had in eighth grade laughed with his older friend, a gaunt white man. With debaucherous glee, the older man—his face’s tight, distorted skin a badge of survival from a time before HIV was more easily hidden—pushed him toward the stage where BELIEVE was dancing.

I first met BELIEVE with Frank, a white queer man I had been following for fieldwork months earlier, in April.1 BELIEVE is Frank’s favorite go-go boy. White. Tall. Muscular. Straight. The word “believe” in black block letters is tattooed across his chest. As Frank and I leaned against the front bar, BELIEVE hung on Frank as he asked us for money.

“I do this to support my kids,” he smiled confidently. Succumbing to the allure of the straight boy—gay for pay—Frank tucked a few dollars down the front of his underwear and received a manly squeeze on the arm with a smile in return.

The December night that Austin and I saw him, BELIEVE supported his kids a few different ways. He squatted on stage, his crotch at eye level as he leaned forward to whisper in the ear of the man in the yellow polo. Three dollar bills in one hand, a vodka soda in the other, the Latino man brushed the bills down BELIEVE’s chest, across his abs, and into the front pouch of his underwear, pulled down to the base of his cock, straining legality. His fingers lingered long enough to feel BELIEVE’s buzzed pubic hair. The Latino man’s giggle turned into raucous disbelieving laughter as he spun around and headed back to his also-laughing friend.

Another go-go boy, this one unsurprisingly also tall, white, and muscular—but gay from the way he twerked his ass as he leaned forward against the back wall—took over the stage for BELIEVE to start to work the crowd.

BELIEVE headed straight for an even more lucrative audience than drunk, older gay men: a young white woman in leopard-skin pants. His demeanor changed completely when he started talking with these women. With the man in the yellow polo, he was cocky, brash. With women, he caressed first. His lips grazed her ear as he whispered softly.

Her taller friend in a white dress and heels egged her on. With this encouragement—permission?—BELIEVE started stroking her thighs as they gyrated. I could see him rubbing his dick against her from behind. It bulged slightly from within his too-tight briefs. They were laughing, obviously having a great time.

With a howl, another group of white women came through the front door. One wore a pink boa, seemingly ignoring the small sign outside against the brick wall: “No Bachelorette Parties.”

Straight people come for the glamour, forgetting sometimes that real people are behind the enchantment as they look to have their own night out on the town. Austin and I took the arrival of this group as our cue to leave what had quickly become a straight strip club. We pressed again through the crowd to reach the front, bursting out into the cold night air onto the corner of Halsted and Roscoe.

“Where do you want to go?” I asked Austin. “Roscoe’s?” I gestured across the street.

With a line of people standing outside, Roscoe’s looked more packed than Cocktail. A bachelorette party emerged through the front door: four white women in heels, dresses too thin for winter, and party tiaras. The lead woman’s tiara read “BRIDE.”

“Jesus. Can we go someplace gay, Jason? I’m not paying a cover for this.” Austin said.

***

Figure 1.1. Hydrate Nightclub, by day and night

From neighborhoods as big as Chelsea or the Castro to places only as big as clubs like the Shamrock in Madison, Wisconsin, or Sidewinders in Albuquerque, New Mexico, gay areas are becoming normal. Straight people flood in. Gay people flee out. Scholars call this transformation assimilation. Some argue that we—gay and straight alike—are becoming “postgay.”2

In There Goes the Gayborhood, Amin Ghaziani argues that gay people can live anywhere now, no longer forced inside the gay ghetto.3 When gay people go to live elsewhere, straight people move into those gay neighborhoods—or gayborhoods, as many of us are fond of calling it—for such amenities as good schools and rising property values. Moreover, gay people can sometimes stay home, living in small towns rather than fleeing to gay meccas. Although no longer essential, dedicated gayborhoods are still needed, Ghaziani contends, to provide gays with some measure of safety and as multicultural enclaves celebrating LGBT identity.4

The years I’ve been studying Boystown, Chicago’s gayborhood, have given me a different perspective: gayborhoods don’t celebrate differences; they create them. Through fostering a space outside the mainstream, gay places allow people to develop an alternative culture, a queer culture that celebrates sex. In gay clubs around America, one learns different values, a way to judge people by different rules. When night falls, we learn new lessons.

Yet these spaces change when sold to a new audience. When queer people arrive on the 36 bus, the Red Line “L” train at Belmont Avenue, or find a parking spot on Pine Grove Avenue, few will be as welcome as white straight women. Those who are sexual deviants, who are genderfucking and trans, who are too brown and black, or who are too poor, Boystown rejects these people now. They don’t fit Boystown’s new image as a gay Disneyland, a safe theme park, a petting zoo.

America is not becoming “postgay,” a label that is laden with homophobia, as though gay identity is a stage to be transcended.5 Gay America is “post-queer.” By shedding the queer elements, Boystown trades sexuality for normalcy. It trades queer sexual connection for legal equality.

“Gay” and “queer”—words often used interchangeably, but referring to different aspects of the homosexual experience.

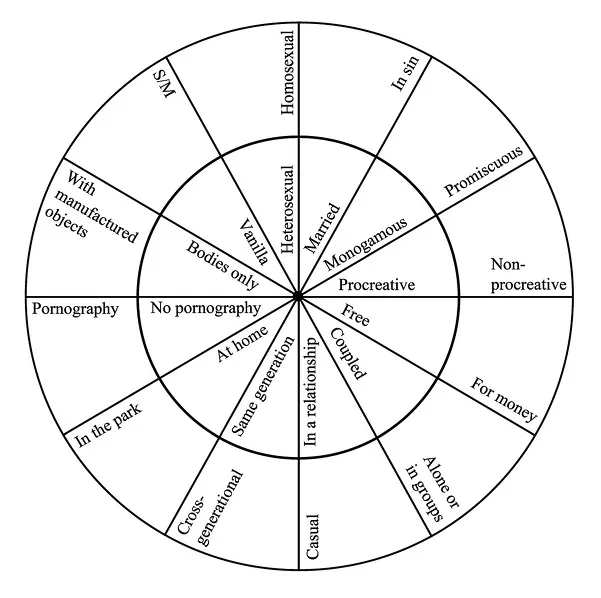

Gayle Rubin’s “charmed circle” diagrams how sexual practices interrelate.6 The circle’s inside wedges are mainstream and hegemonic. These practices represent how good moral, normal people have sex. The outside practices oppose these wedges. Society stigmatizes these subversive sexualities. Sex in the outer limits is queer.

Only one wedge describes sexual orientation, the person’s sex/gender with whom you are having sex. The other practices are other sexual aspects: the place, timing, group composition, and so forth. These other traits became the basis of stereotypes. Sexual deviant. Promiscuous. Slut. AIDS ridden.

Figure 1.2. The charmed circle

Facing one section’s stigma, gay communities also reject the other wedge’s morality—or they did. If you question the morality of discrimination because of who you love, you might also question the morality of other sexual decisions. The inside wedges join together against the outside circle. One must follow all these practices to escape stigma.

The homosexuality/heterosexuality wedge is unique. Homosexuality became an identity. Being gay is an orientation. Today, society considers sexual orientation essential to one’s being. A political movement transformed conventional sexual morality by creating gay identity.7

The U.S. Supreme Court recognized this change as well. Bowers v. Hardwick held sodomy laws constitutional because the law regulated conduct.8 Lawrence v. Texas reversed Bowers because homosexuality is an immutable identity.9 Homosexuals gained legal rights by proving essential identities. Gays and lesbians are oppressed classes of people. The state can regulate conduct. The court did not protect a right to have sex as we choose.

Therefore, in Ruben’s circle, we also see how assimilation works. If a boundary disappears, then acceptance into the inner circle means new morals. Gay neighborhoods stay gay—affiliated with homosexuality—but they become less queer, stripped of the outside’s alternative sexuality.

Gay identity versus queer sexuality. Old divisions, a familiar dynamic. Nearly twenty years ago, Michael Warner wrote about the disconnect between queer liberation and gay assimilationist movements.10 Lisa Duggan warned us of “homonormativity,” a white, gay male, upper-class, family-man normality.11 Almost a decade ago, Jane Ward saw a new “respectable” queer.12 Gay movements want a return to privilege’s embrace; queer movements resist the inner circle’s vice grip.

We stand now on a new edge. The gay movement won marriage, military inclusion, legitimacy, and legal rights. How has life in the gayborhood changed? Are gay men normal? Is queer sexuality banished, destined for extinction? Or can we still learn the lessons of the night?

***

Austin never wants to go to Roscoe’s. The mix of dollhouse decorations, dark wood, and too-earnest baby gays isn’t his scene. The bachelorette party and cover charge were a convenient excuse to pull us out of line.

The Lucky Horseshoe, however, has a darker scene.

White cocktail napkins billowed like tumbleweeds down Halsted in the warm winter air. The streets, though, were far from deserted. Once the cold starts to settle in around November, even the slightest rise in temperature brings people out onto the streets. With so little time outdoors, many will take any chance they can get. During the summer, the crowds can get even worse. With a huge mass of people, density and heat means fission. At times, violence erupts.

Boystown is an entertainment district: a neighborhood with residences but also a theme park for gay desire. Groups of people walk along the street at night. Some bar hop, going from ride to ride, getting lost in the Disneyland magic of the night. For others, that magic is the street.

We walked down Halsted Street, holding hands in the one place we can. A bit drunk, Austin and I were laughing at each other’s jokes. He swept me up in his arms and planted his lips on mine.

“Woooo! Do it again!” a white woman screamed at us, poking her head out of a passing cab.

Crossing Belmont, we escaped into the Lucky Horseshoe, the windows tinted in faux shame.

Figure 1.3. The Lucky Horseshoe Lounge

The Lucky Horseshoe is nothing like a straight strip club, no matter the similarities between people dancing on the bar for tips and private dances in the back. The boys working for tips in their jockstraps take their cue more from their drag queen sisters than from their similarly scantily clad stripper kin.

The front center stage, surrounded by the namesake horseshoe bar, had a cute dancer: his beefy football body squeezed into the usual too-small jockstrap, the jiggle of his meaty ass overhanging the squeezing straps.13 However, I wasn’t there to watch the dancers, and it was too busy to find a space at the bar. We pushed past the crowd to the middle bar where the dancers hung out between sets, and, like BELIEVE, they tried to talk men out of their dollars rather than dancing for them. Someone walking out of the bathroom—no more than two small swinging saloon doors concealing a toilet—almost ran into us, but we got situated at two stools down at the end of the long line bar, opposite the video poker machine that the dancers congregated around.

We like the Shoe, as Boystown regulars call it, because it is literally dirty enough that no bachelorette would venture in. But also dirty in the good way. Between the inhospitable—some might say sexist—bathroom arrangements, skeezy vibe, and the almost tragic dancers who seldom have the same level of muscularity or masculine Chippendales’ attitude Cocktail’s dancers have, the Shoe is not the party destination for straight women looking for a night out on the town.14

Instead, everyone else in Boystown seemed to have congregated here. The Shoe seems overrun with hot men, much busier than normal, making it hard to get a drink. As Boystown’s gay clubs fill with straight women, these raunchy spaces are doing better, are more popular. Finally flagging a bartender, I ordered us two whiskeys on the rocks to sip while we watched the crowd.

As I did at Cocktail, I eavesdropped and observed. Clumped in groups, men stood and handed money to the men on stage. The stripper within eyeshot of our stools flexed his arms at the older white man stuffing money down his underwear. Turning around, he showed off his muscular black ass, only a thin line of fabric holding the thong in place.

The Shoe felt like a sexy haven in the gentrified wilderness. Queer in the midst of gay clubs playing nice for straight dollars. A cozy dark corner from Boystown’s newfound light. The Shoe echoes an earlier time—perhaps a time living only in our nostalgia—for the nightlife of dark rooms, a people bound together by shame, and the sexual thrill that came from doing it anyway.

***

Sex is important.

Americans consider sex private, yet we talk about nothing else. Sexuality is an intimate experience that defines our public lives.

During the day, we get married. We form families. We raise kids. We choose careers. We work our bodies, fashion our clothes, and buy products to sway others’ opinions. We make choices so others see us as good, attractive, normal people. The right kind of person.

During the night, when darkness shrouds the world, Boystown flickers to life. The “wrong” person emerges. The kind that has sex in public. The kind that has sex with...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- 1. Nightfall

- 2. On Safari

- 3. Naked Intimacy

- 4. Sexy Community

- 5. Sexual Racism

- 6. New, Now, Next, Not

- Midnight

- 7. Gay Disneyland

- 8. Becoming Gay

- 9. One of the Good Gays

- 10. Straight to Halsted

- 11. Girlstown

- 12. Take Back Boystown

- 13. Queer Is Community

- 14. Dawn

- Acknowledgments

- Supplement: Producing Ethnography

- Notes

- References

- Index