eBook - ePub

Building for the Arts

The Strategic Design of Cultural Facilities

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Over the past two decades, the arts in America have experienced an unprecedented building boom, with more than sixteen billion dollars directed to the building, expansion, and renovation of museums, theaters, symphony halls, opera houses, and centers for the visual and performing arts. Among the projects that emerged from the boom were many brilliant successes. Others, like the striking addition of the Quadracci Pavilion to the Milwaukee Art Museum, brought international renown but also tens of millions of dollars of off-budget debt while offering scarce additional benefit to the arts and embodying the cultural sector's worst fears that the arts themselves were being displaced by the big, status-driven architecture projects built to contain them.

With Building for the Arts, Peter Frumkin and Ana Kolendo explore how artistic vision, funding partnerships, and institutional culture work together—or fail to—throughout the process of major cultural construction projects. Drawing on detailed case studies and in-depth interviews at museums and other cultural institutions varying in size and funding arrangements, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Atlanta Opera, and AT&T Performing Arts Center in Dallas, Frumkin and Kolendo analyze the decision-making considerations and challenges and identify four factors whose alignment characterizes the most successful and sustainable of the projects discussed: institutional requirements, capacity of the institution to manage the project while maintaining ongoing operations, community interest and support, and sufficient sources of funding. How and whether these factors are strategically aligned in the design and execution of a building initiative, the authors argue, can lead an organization to either thrive or fail. The book closes with an analysis of specific tactics that can enhance the chances of a project's success.

A practical guide grounded in the latest scholarship on nonprofit strategy and governance, Building for the Arts will be an invaluable resource for professional arts staff and management, trustees of arts organizations, development professionals, and donors, as well as those who study and seek to understand them.

With Building for the Arts, Peter Frumkin and Ana Kolendo explore how artistic vision, funding partnerships, and institutional culture work together—or fail to—throughout the process of major cultural construction projects. Drawing on detailed case studies and in-depth interviews at museums and other cultural institutions varying in size and funding arrangements, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Atlanta Opera, and AT&T Performing Arts Center in Dallas, Frumkin and Kolendo analyze the decision-making considerations and challenges and identify four factors whose alignment characterizes the most successful and sustainable of the projects discussed: institutional requirements, capacity of the institution to manage the project while maintaining ongoing operations, community interest and support, and sufficient sources of funding. How and whether these factors are strategically aligned in the design and execution of a building initiative, the authors argue, can lead an organization to either thrive or fail. The book closes with an analysis of specific tactics that can enhance the chances of a project's success.

A practical guide grounded in the latest scholarship on nonprofit strategy and governance, Building for the Arts will be an invaluable resource for professional arts staff and management, trustees of arts organizations, development professionals, and donors, as well as those who study and seek to understand them.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building for the Arts by Peter Frumkin,Ana Kolendo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Idea of Strategic Design

“It’s not surprising that there’s no art in it. Art couldn’t compete,” wrote Boston Globe architecture critic Robert Campbell in his 2002 review of the then-new Quadracci Pavilion of the Milwaukee Art Museum.1 This $130 million building had a massive hydraulically powered sunshade that slowly undulated, like the wings of a swan. The new building’s 142,050 square feet mostly contained public spaces, all making a grand architectural statement and catapulting the Milwaukee museum to the status of an architectural landmark. Visitors and tourism increased, yet many came to see the building rather than the collection inside. By moving public spaces to the addition, the main museum building was able to increase its gallery space. The building’s initial plans had called for a budget of $35 million. Eventually, Santiaga Calatrava’s bold architectural concept convinced the board to raise this budget to $100 million. Cost overruns during construction added another $30 million to the price tag, resulting in a facility that cost $130 million—and contained little additional space for the display of art from the Milwaukee Art Museum’s collection.

Milwaukee’s approach posed a fundamental question about what purpose an art museum building is supposed to serve. To some extent, the Quadracci Pavilion was a metaphor. Its absence of galleries embodied the cultural sector’s worst fears: that buildings now existed just for buildings’ sake, that resources were increasingly dedicated to facilities and attention-drawing marquee architecture over collections, and that art in the collections was being symbolically and literally displaced by other concerns.2

1.1 Milwaukee Art Museum’s Quadracci Pavilion. Photo by Steven Andrew Miller.

The outcome also provided a chilling insight into the question about the harm that a single building project could do. The Quadracci Pavilion left the Milwaukee Art Museum with over $30 million in unanticipated debt. Annual interest payments reached over $1 million. With a new expensive building to maintain, operating costs increased dramatically. Whereas before the expansion, the endowment covered 25 percent of operating costs, after expansion the same endowment covered only 8 percent. Years of massive budget deficits—$3.3 million in fiscal year 2003 and $2 million in 2004—followed. The Milwaukee Art Museum was eventually able to right itself, raising money to pay off the debt through a herculean effort that commandeered all the organization’s energies. The museum’s time on the brink called attention to the havoc some new buildings wreak on the arts organizations they are intended to benefit. See figure 1.1.

In the early 2000s, stories like the Milwaukee Art Museum’s—narratives about building projects followed by cost overruns, scheduling delays, mounting deficits, staff layoffs, cuts in opening hours, decreases in the number of artistic productions—became increasingly common in the news. Problems related to ambitious building programs surfaced in places ranging from Miami, Florida, to Madison, Wisconsin. Of course, stories of triumphs, like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, appeared as well, fueling the dream of institutions to build their way to relevance and transformation. Some arts institutions with new buildings were plunged into crises, while others flourished after completing their constructions.

In this book, we suggest that these differences in outcomes can be understood by examining the strategy and tactics deployed in capital projects. But what do we know about effective strategy for cultural facility construction? Our answer begins with understanding the quality of the match between the local community needs and the available arts offerings, then considers the four most critical dimensions of the strategic planning process.

To Build or Not to Build

One of the first strategic questions that must be answered is whether a building project should be undertaken at all. Any answer to this question must begin with a consideration of the relationship between the arts organization and its community, which in the ideal scenario is mutually beneficial. For arts organizations, their host communities can be a source of philanthropic and public funds, skilled volunteers, and loan or bond guarantees. The host community is also an arts organization’s source for both creative and operational partnerships, from small groups with whom they can collaborate to larger museums, performing arts centers, and universities, who may offer space, operational subsidies, and technical assistance. Last but not least, arts organizations look to their communities for opportunities to connect, serve, and have an impact.

In exchange, communities benefit primarily from the availability of artistic experiences. Cultural offerings enhance the community’s quality of life. At their best, the arts can unify people through a shared experience. In addition, some arts organizations provide educational programs in the schools, pioneer community revitalization efforts, as well as spur economic development.3 Though generally seen as desirable by the communities, this development can occasionally—when linked to gentrification—have the negative effect of displacing lower income families when the cost of living and value of real estate increase. The arts also contribute to a community’s reputation by building cultural cachet and prestige. Both new buildings and the renovation of old buildings into arts facilities serve as monuments to civic pride and community commitment.

Yet these relationships do not always benefit each partner equally, and in some cases, community or artistic leaders look to a new facility to fix deeply rooted problems. Projects can and do become projection screens for dreams. An opera may hope for larger turnouts and greater revenues at a different location. A museum might hope that a larger, better space will help it convince collectors to make significant bequests. A city may hope that its local groups, if given a better equipped facility, will meet its citizenry’s expectation for skill and artistic vision. The proponents of construction projects claim that the quality, quantity, and diversity of artistic experiences available to the public will increase, that access will be made easier with features like prominent facades and greater space to accommodate school groups, and that a better, larger space and upgraded amenities will boost operating income and the financial sustainability of the arts. A cultural edifice is also sold as an aid to a neighborhood’s economic development, a spur to tourism, and a contribution to a city’s quality of life. In short, new cultural facilities can benefit both the community and its artists. At least in theory, that is.

The opportunity to realize these benefits is predicated on the existence of a strong and balanced relationship between the arts and their community. If the interests of the community and the local arts organization are not well matched, a new building and the attendant shared responsibilities and conflicting expectations have the potential to stress rather than strengthen an imperfect marriage between these partners. Take for example the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, a $325 million facility that in 2011 found itself in the middle of the news story about the bankruptcy of one of its tenants, the Philadelphia Orchestra. The orchestra had sought bankruptcy protection in order to renegotiate its lease, citing among other reasons an increased financial burden when the occupancy costs at the Kimmel were compared with its old facility. Just a year before, the Kimmel had laid off its own programming and educational staff in order to cut its resident companies’ costs. Its own series of presented programs, which was meant to serve a larger audience than that of the classical companies, was crippled as a result. Even nine years after opening, the financial obligations incurred by building a new venue still managed to force a choice between the artistic missions of individual companies and a performing arts center’s mission to serve a diverse set of constituents. Moreover, the conflict of interests between various stakeholders landed the Kimmel in the center of a controversy, exposing a strained relationship. Before any building project in the arts is undertaken, a serious and objective examination of the match between the host community and the programs that will be presented in the new space needs to be undertaken.

The quality, quantity, and variety of artistic experiences made available to the community may each give rise to a mismatch between the level of community support available to the arts and the level of artistic assets available to the community. The question here is not just about taste, though in some communities taste is a factor. Performances of Racine and Wagner and exhibitions of European religious paintings, no matter how canonical and no matter how skillfully presented, may not flourish in cities with young populations with countercultural norms. Conversely, a staging of a Shakespeare play that includes frontal nudity and hip-hop references may cost a theater its community support regardless of the skill and sophistication of the production if its audience is conservative in its tastes. An extremely diverse community may, however, accommodate and demand many types of programming. Yet the question of the match between the host community and its art also involves questions of volume and quality. Sometimes, a community may have an excellent, popular local theater or a museum that is incapable of producing enough performances or exhibits to fully satisfy its community’s demands. At other times, an arts group’s struggle to connect to its community may be rooted in the issue of quality—the fact that its programs may have suitable ambitions and availability, but fail on the level of execution. Thus, when considering whether a community and the artistic experiences made available there are well matched, leaders must weigh not only the quality of the available programming, but also its philosophy, variety, and quantity.

Similarly, a community’s needs and assets must be matched to the capacity of an arts organization if a new facility is to work. If attendance is already a problem, an expansion of programs is unlikely to succeed. Enough funding must be available for current operations before a capital project and greater operating costs can be considered. Creative and operational partnerships must be fruitful and strong before multiple groups begin to jointly provide the programming and financial support for operations of a new venue. Board members and other volunteers must have the skill set to effectively oversee and advocate for an artistic institution before they undertake a capital campaign and a project that tests the strength of their commitment and their financial prudence. Broad and deep community support for current artistic programs is needed before a new facility is undertaken.

This assessment of the quality of the match between the community and the arts that are produced is likely to be difficult and require objective, skilled observers with local expertise. Descriptive data, such as audience size and whether its composition is representative of the community at large, may be a rough starting point for establishing the quality of this match, but these data will never provide the full picture.4 Not surprisingly, few if any professional consultants who specialize in guiding communities and artistic institutions through capital projects are willing to offer evaluations of artistic merit or audience sophistication. In the interests of being cordial and avoiding offending someone, few arts leaders like to discuss these topics. Still, the issue of a quality match is real. The key is to have an open examination of these issues and to work on identifying and fixing obvious mismatches before embarking on a major capital project.

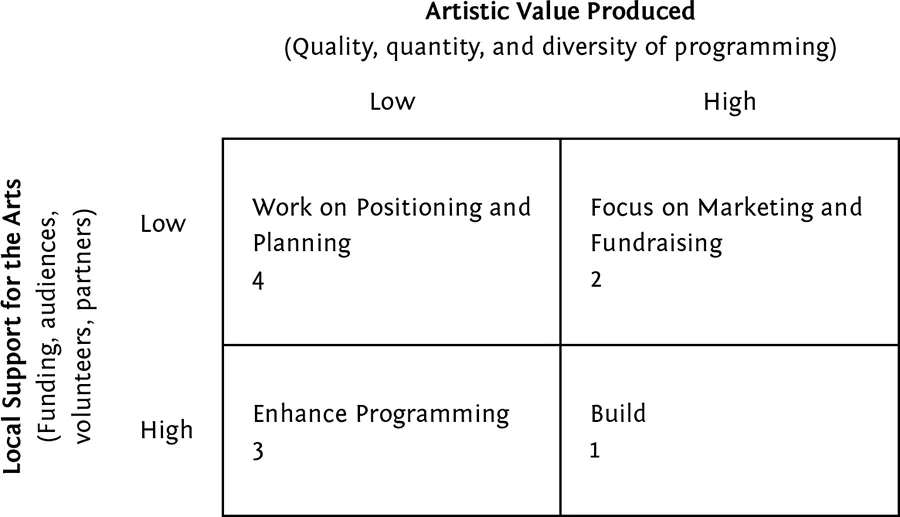

The appropriate response for an arts organization contemplating a building project depends on the match between the artistic value offered with the level of community support present. The interaction of these two dimensions can be summed up with a matrix with four cells (see table 1.1). In scenario 1, the artistic offerings and community needs are well matched, and the artists and the community can readily consider the expansion of cultural facilities. In the other scenarios, the needs of an arts organization are not aligned with the community assets, or the needs of the community are not well matched with what the organization can offer. In almost all cases, a good match needs to be achieved before beginning any attempt to build. Otherwise, the cultural vitality of the community and the arts organizations’ ability to execute their missions may be imperiled. Too many organizations build with the hope that the match will be enhanced, only to find that the opposite happens. When the project is framed and pursued during a period when the artistic value produced is aligned with community demand, the entire building process becomes far less contentious.

In scenario 2, the arts organization considering a building project finds the community satisfied with the type, quality, and quantity of its programming and yet the level of community support is insufficient. This group’s primary tasks should be marketing and fundraising.5 Its tactics could include diversifying and expanding its funding sources and locating sources of funding external to the community, like state and federal governments and foundations. The group may undertake an awareness-building campaign meant to expand a culture of giving in its community. It may embark on an audience educational campaign to foster an appreciation of its art form among a greater portion of the community, thereby increasing its ticket revenues. If the problem is the size of the audience, the group may also seek funding for a reduced-price ticket program to make its programming more affordable for a larger portion of its community. The group may seek partners like existing groups, museums, theaters, and universities to share or underwrite operating expenses. All these initiatives could help form a better match between the community and the arts by either reducing the need of arts organizations for community assets or by increasing the availability of these resources. Ideally, these initiatives ought to be undertaken first, before a building project begins.

Table 1.1. Value and Support

In scenario 3, an arts organization struggles to connect with the abundant audiences, donors, volunteers, and partners in its host community. Many times, a group in this position will attempt to prove its worth to its community by expanding its mission to include universally acclaimed goals like education, environmental sustainability, or community outreach programs and events unrelated to its art form. In the end, however, an artistic institution will live or die by its programming. Thus, the first focus of a group in this kind of position should be on enhancing the quality and quantity of its programming. A theater group can develop its artistic talent pool through training and recruitment. A museum can focus on the development of its collection and curatorial staff. Creative collaborations with others may prove fruitful. The group may also need to examine its programming philosophy and assumptions and evaluate whether they fit with their host community’s expectations and culture. If not, the group needs to either educate and convince its prospective audience or move to a more hospitable environment. In the end, the development of the group’s programming is the path most likely to result in a mutually beneficial, supportive, long-lasting relationship with its community.

In scenario 4, a group finds itself struggling to produce quality programs in a community that lacks the resources to support them. A museum or a new theater may fail to take hold in a rural community with few other existing institutions and little money for support. Its leadership needs a strategic plan for how to both develop artistic capabilities and ensure financial sustainability. Many of the tactics listed above may still work, though for this group the journey toward a quality match will prove long and arduous. Fixing one side of this equation is challenging. Fixing both sides is daunting. As a consequence, big questions will arise about whether to soldier on or start over somewhere else.

Realistically assessing the quality of the match between an organization’s art and the local community is therefore fundamental to making a rational decision to engage in planning, marketing and fundraising, programming, or building. However tempting and desirable it might appear on the drawing board, a new facility is unlikely to prove to be a shortcut to success for any arts organization that finds itself badly matched with its community. Strategies for building a quality match must be pursued first, before any building project can be sensibly contemplated.

Strategic Design and the Four Cornerstones of Cultural Building Projects

If the decision to build is made, there are four main forces that animate cultural building projects that must be taken into account while answering the next question—namely, how to build. First, there is the desire to elevate artistic quality and enhance mission achievement. For museums, expansions are a way to show more art and to enhance an organization’s ability to acquire or borrow through gifts and institutional loans. After all, few collectors want to bequeath objects only so they can languish in storage. For performing arts organizations, new buildings can also mean an increase in the quantity and quality of programs through benefits like an increase in the availability of leasable dates and the ability to attract better performers. To some extent, such issues can be solved by increases in budgets rather than changes in physical facilities. Others—like leaking pipes and bad lighting in galleries, sight line obstructions and dead acoustics in performance venues—can be resolved only through either a move or a renovation. Thus, facility shortcomings can affect program quality, and this sometimes serves as the impetus to cons...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Idea of Strategic Design

- 2. Elements of Building Decisions

- 3. Seeking Funding

- 4. Connecting to Community

- 5. Growing Operational Capacity

- 6. Refining Mission

- 7. Seeking Strategic Alignment

- 8. Better Building for the Arts

- Notes

- Index