- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Today, predicting the impact of human activities on the earth's climate hinges on tracking interactions among phenomena of radically different dimensions, from the molecular to the planetary. Climate in Motion shows that this multiscalar, multicausal framework emerged well before computers and satellites. Extending the history of modern climate science back into the nineteenth century, Deborah R. Coen uncovers its roots in the politics of empire-building in central and eastern Europe. She argues that essential elements of the modern understanding of climate arose as a means of thinking across scales in a state—the multinational Habsburg Monarchy, a patchwork of medieval kingdoms and modern laws—where such thinking was a political imperative. Led by Julius Hann in Vienna, Habsburg scientists were the first to investigate precisely how local winds and storms might be related to the general circulation of the earth's atmosphere as a whole. Linking Habsburg climatology to the political and artistic experiments of late imperial Austria, Coen grounds the seemingly esoteric science of the atmosphere in the everyday experiences of an earlier era of globalization. Climate in Motion presents the history of modern climate science as a history of "scaling"—that is, the embodied work of moving between different frameworks for measuring the world. In this way, it offers a critical historical perspective on the concepts of scale that structure thinking about the climate crisis today and the range of possibilities for responding to it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Climate in Motion by Deborah R. Coen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2018Print ISBN

9780226752334, 9780226398822eBook ISBN

9780226555027* 1 *

Unity in Diversity

CHAPTER 1

The Habsburgs and the Collection of Nature

In 1867 Anton Kerner von Marilaun made a historic discovery in the mountains northwest of Innsbruck, where he was professor of botany. To explain its significance, he was obliged to turn back three hundred years. It was then, in the mid-sixteenth century, that the cultivation of auriculas (see figure 3) had caught on in Holland and spread to England and beyond, triggering a demand for the flowers second only to the craze for tulips. The auricula was, to Kerner’s knowledge, the only Alpine flower to have become a “widespread ornamental plant in gardens.”1 High-born ladies had enjoyed an abundant selection of these beauties at Viennese markets. But the geographical origin of the auricula was unknown, and Kerner set out to uncover its story.

Figure 3. Illustration of an auricula by Clusius, 1601.

Kerner’s historical detective work led him to the writings of Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), perhaps the most celebrated European naturalist of the sixteenth century. Clusius, from Flanders, had come to Vienna in 1573 at the bidding of Emperor Maximilian II, who sought to collect everything that was rare, beautiful, or useful in nature.2 The Flemish botanist was tasked with developing a medical garden for the imperial palace. As Kerner noted, gardeners proved eager to send Clusius plants. Many varieties came from the Mediterranean, others from Turkey and the Banat.3 Clusius, meanwhile, had an uncommon passion for Alpine flowers. In fact, he took great pains to grow these high-altitude plants in Vienna. Even his failures were instructive, as Kerner explained. It appeared that many Alpine varieties were unhappy with the warmer conditions in Vienna, even if some managed to thrive in the garden’s shadier spots. In the end, Clusius was able to cultivate two varieties, which Kerner identified by their Linnaean names, Primula auricula L. and Primula pubescens Jacq. The latter, according to Kerner, was a hybrid of the former and another variety. The hybrid, which came to be known simply as the auricula, reproduced vigorously and with dazzling variations.4 It found its way from Vienna to merchants in Antwerp and soon became the basis of the new botanical craze.

But where had the flower come from? Clusius had first encountered and described auriculas in the Vienna garden of the physician Johann Aichholz.5 All Aichholz knew was that the plant had been a gift from a noblewoman. Hearing that the auricula was common “in the Alps near Innsbruck,” Clusius set out to find it. This was a remarkable undertaking in an age when mountains were still regarded as godforsaken wilderness.6 Yet Clusius searched “the highest passages of the Austrian and Styrian Alps in vain.”7 To later generations of botanists, the origins of the auricula remained a mystery. Many searched the Alps for it, but it was nowhere to be found in the wild. That is, until 1867, when Kerner first discovered the plant (Primula pubescens Jacq.) growing amid limestone and slate on a steep hill above the village of Gschnitz, at an elevation of seventeen hundred to eighteen hundred meters. This discovery meant so much to Kerner that he chose to build a summer villa for his family on that very site. In 1874, when he was ennobled by Emperor Franz Josef in recognition of his scientific service to the state, the auricula became the basis for his family’s coat of arms.

One might wonder why the flower’s origin had remained a mystery all this time. As we will see in chapter 10, Kerner would glimpse a possible answer to that question as he began to decipher the climatic history of the eastern Alps. For the present chapter, the question is this: why would a nineteenth-century scientist have worked so hard to reconstruct the efforts of a plant collector who had been dead for three centuries? As director of the botanical gardens in Innsbruck in the 1860s and later in Vienna, Kerner believed he could not reform these institutions without understanding their historical development. In order to chart a course for the future, one needed to appreciate “how, in the course of time, botanical gardens had come to possess the collections that we find in them today.” The director needed to know not only what the garden contained, but why. He had to learn to read the garden for clues to the “state of botany at the time. . . . The dominant ideas of an age in the sciences are like the air we must breathe. They have a refreshing and invigorating influence not only on the intellectual lives of individuals, but also on all our institutions.”8 Kerner’s point was that the garden was an archive for the study of both natural history and the history of natural knowledge.

This argument signals Kerner’s intention to contribute to the writing of imperial history. The discipline of imperial or “whole-state” (Gesamtstaat) history had first emerged at Habsburg law faculties in the early nineteenth century, when its goal had been to piece together the legal basis of the dynasty’s “historic rights” to the crown lands.9 By the 1860s, however, this narrow vision had expanded. In the words of the historian and imperial adviser Joseph Chmel, the historian now had a “far more difficult, but all the more valued responsibility”: to explain the Austrian Empire as “one of the most remarkable natural phenomena, as a practical solution to a daunting problem of nature”—that is, the problem of uniting “the most varied nationalities and education levels in one state.”10 This new imperial history would recover the development of the arts and sciences in the Habsburg lands since 1526; it would promote “the intellectual union of the Austrian lands.”11 Documenting the natural world region by region was central to this initiative. “Is it not part of a region’s history to know how it has come to be and how it has gradually taken shape; to know on what kind of ground we are standing . . . ? . . . The oldest regional history is furnished by the work of the geologist, the physicist, the geographer; their research must teach us how Austria gradually took form.”12 Imperial history would have to include both a history of natural science in Austria and an account of the development of the natural environment itself.13

This chapter considers the consequences of this project for the production of climatological and related knowledge in nineteenth-century Austria. The long rule of the Habsburg dynasty in central Europe ensured that environmental knowledge accumulated in repositories of many kinds, including botanical gardens, libraries, mineral collections, herbariums, weather diaries, and map collections. In these institutions, nineteenth-century scholars found material for their own histories of nature, science, and empire.

THE BIRTH OF THE IMPERIAL IDEA

Anton Kerner looked back at the late sixteenth century and saw a crucial turning point in the history of natural knowledge. Not only did the wellborn begin to devote their leisure time to travel and collecting. They also began to take a scholarly interest in “domestic”—or what we might call “indigenous”—nature.14 These trends were manifest in the reorientation of princely gardens from narrowly medical purposes to the collection of “wonders,” whether native or exotic. This quest for nature’s wonders was fueled by the ambitions of Habsburg princes.

In 1526 the Habsburgs met with the good fortune that would define their political predicament for the next four hundred years. Hungary had been defeated by the Ottomans at the Battle of Mohács. The death of the Hungarian king on the battlefield and a complicated set of marriage agreements left the house of Habsburg with both the Hungarian and Bohemian crowns. In this way, the Habsburg Monarchy became a strange new beast, “a complex composed of different and overlapping historico-political, ethnic, and later, also administrative units.”15 In what were known as the Austrian hereditary lands (including Upper Austria; Lower Austria; the duchies of Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola; the principalities of Istria, Gorizia and Trieste; and the more recently acquired county of Tyrol), the power of the dynasty was already established. Its authority was much looser in the remaining lands of the Holy Roman Empire, which the Habsburgs ruled continuously (with the exception of one five-year gap in the eighteenth century) from 1438 until its dissolution in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars in 1806. Thus the Habsburg lands resembled a Venn diagram of partially overlapping dominions: Hungary and Croatia lay outside the Holy Roman Empire, while many of the German principalities lay outside the Austrian hereditary lands.

The territorial windfall that the Habsburgs received in 1526–27 was a mixed blessing from the start. The Ottoman Empire was still in control of parts of Hungary and poised to expand further north and west. Concurrently, the Protestant Reformation was threatening to rip apart the Holy Roman Empire. Emperors Ferdinand I (king of Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia from 1526 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1558 to 1564), Maximilian II (1564–76), and Rudolf II (1576–1612) all attempted to stave off a direct confrontation between Catholic and Protestant rulers, while presenting themselves as defenders of Christendom against the Ottomans. Not until the early seventeenth century would the Habsburgs abandon this policy of irenicism and embark on the forceful suppression of Protestantism.16 The sixteenth-century Habsburg rulers styled themselves as heirs to a universalist legacy—that of the ancient Roman Empire and of the “Holy Roman Empire” founded by Charlemagne in the year 800.

NATURE AND EMPIRE

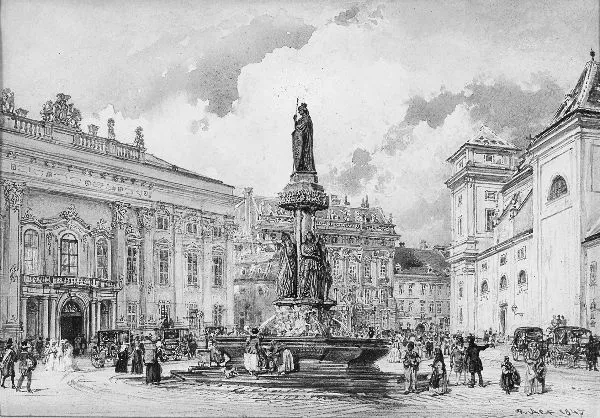

In Kerner’s own day, in the face of burgeoning nationalist movements, the house of Habsburg was revisiting older ideas and symbols. The Renaissance iconography of Habsburg power got a new lease on life. Architects, for instance, crowned countless buildings with female figures meant to personify Austria, an allegorical motif that dated back to the late sixteenth-century reign of Rudolf II. Likewise, nineteenth-century sculptors designed fountains to illustrate the convergence of the Monarchy’s four principal rivers, mimicking a famous water feature built for Rudolf’s father, Maximilian II (see figure 4). The 1860s and 1870s even saw a renaissance of tableaux vivants, in which actors enacted allegories of imperial unity, just as princes and princesses had done at the Habsburg courts of the sixteenth century.17 As we will see, allusions and artifacts like these were part of a modern visual and material culture that preserved an older way of thinking about nature and empire, in terms of an intimate relationship between microcosm and macrocosm.

Figure 4. Wien, Freyung mit Austriabrunnen, by Rudolf von Alt, 1847. Von Alt’s watercolor illustrates the newly erected fountain, featuring allegories of the four major rivers of the Austrian territory at that time, the Danube, Elbe, Po, and Vistula.

It was in the sixteenth century that Habsburg rulers had begun to link the careful observation and representation of the natural world to their political ideal of universal harmony. Like many other European rulers of their day, the Habsburgs sought to demonstrate their power by displaying collections of rarities. From the late sixteenth century, in northern Europe and Italy, it became common for princes to house cabinets of curiosity or Wunderkammer. The category of “wonders” included rare specimens of animate and inanimate nature (naturalia), marvelous works of art (artificialia), and ingenious scientific instruments (scientifica). Many Renaissance natural philosophers believed that objects in nature contained hidden, symbolic meanings. Things pointed beyond themselves to a web of interrelations, which might link a given species to seemingly unrelated objects and, ultimately, to the cosmos as a whole. Individual objects might therefore provide symbolic or perhaps even magical control of the world at large. Paracelsus, a physician and alchemist at the court of Maximilian I, used the skills of artisans to show how power over the world could be derived from the imitation of nature’s own creative processes.18 Thus Wunderkammer conveyed the message that power over nature constituted power over the human world.19

As Kerner noted, the sixteenth century also saw the rise of a new, empirical approach to natural knowledge. In fact, more recent historians have argued that collections of wonders played an essential role in stimulating the close observation of natural specimens. Accordingly, the meaning of scientific “experience” began to shift from an Aristotelian ideal of knowledge of the common course of nature, to a modern emphasis on knowledge of particular “facts.”20 This was a global phenomenon, in the sense that such collections could eventually be found in many parts of Europe, and they in turn depended on networks of exchange with Africa, Asia, and the New World. Within this global historical transition, the collections of the Habsburgs were of special significance. In the judgment of historian Bruce Moran, “it was especially at the courts of the imperial Hapsburgs that collections grew to unprecedented proportions.”21

The Habsburgs sought to illustrate the universality of their rule by expanding their collections to a truly encyclopedic scope. Three were particularly noteworthy. The cabinet of Ferdinand II of Tyrol (1529–95) in Ambras Castle, outside of Innsbruck, was famous for its variety of natural objects.22 The gardens and menageries of Ferdinand II’s brother, Emperor Maximilian II, were renowned for their rare plants and animals, including medicinal plants from the Americas, tulips from Turkey, and an elephant that arrived in Vienna in 1552.23 Even more remarkable than these two was the collection of Maximilian II’s eldest son, Emperor Rudolf II, who moved his court to Prague.

Rudolf’s collection included works of art, beautifully crafted scientific instruments, such as terrestrial and celestial globes, but also minerals, plants, and animals.24 Thomas Kaufmann, the leading interpreter of Rudolf’s collections, argues that the emperor prized his collections as a microcosm of the world he sought to rule. His castle in Prague contained a wing specially designed to house the collection, with an anteroom decorated with cosmic motifs: Jupiter, the four elements, the twelve months of the year.25 Likewise, his gardens were designed with mathematical precision and according to classical architectural theory, such that garden and museum could “serve as a key to the understanding and study of the harmony of the creative universe.”26 Other princes may have harbored similar aspirations, but Rudolf turned the dream into a systematic enterprise, recruiting an entire team of naturalists to seek out natural wonders and learn their powers. What’s more, historians consider Rudolf’s collection to mark the origin of the institution of the research museum, where naturalists could study specimens in person. Unlike most Wunderkammer, these displays were not arranged to dazzle the viewer, but to invite patient attention.27

Like Rudolf II’s naturalia, works of art on display at Habsburg courts often carried a political message. Paintings and sculptures represented the dynasty’s universal dominion by evoking subtle interconnections between microcosm and macrocosm. For instance, a fountain designed by Wenzel Jamnitzer for Maximilian II and completed in 1578 was an ingenious incarnation of the Habsburgs’ aspiration to govern a universal realm. Symbolized by an eagle, their empire soars over figures representing aspects of the natural world: the four elements, the rivers of the dynasty’s lands (Rhine, Danube, Elbe, and Tiber), and the four seasons, all crowned by a celestial globe.28 The eagle is thus the instrument of union among parts of the natural world existing at different scales, spatial and tempor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- Introduction: Climate and Empire

- PART 1 Unity in Diversity

- PART 2 The Scales of Empire

- PART 3 The Work of Scaling

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index