eBook - ePub

Fusion of the Worlds

An Ethnography of Possession among the Songhay of Niger

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"This ethnography is more like a film than a book, so well does Stoller evoke the color, sight, sounds, and movements of Songhay possession ceremonies."—Choice

"Stoller brilliantly recreates the reality of spirit presence; hosts are what they mediate, and spirits become flesh and blood in the 'fusion' with human existence. . . . An excellent demonstration of the benefits of a new genre of ethnographic writing. It expands our understanding of the harsh world of Songhay mediums and sorcerers."—Bruce Kapferer, American Ethnologist

"A vivid story that will appeal to a wide audience. . . . The voices of individual Songhay are evident and forceful throughout the story. . . . Like a painter, [Stoller] is concerned with the rich surface of things, with depicting images, evoking sensations, and enriching perceptions. . . . He has succeeded admirably." —Michael Lambek, American Anthropologist

"Events (ceremonies and life histories) are evoked in cinematic style. . . . [This book is] approachable and absorbing—it is well written, uncluttered by jargon and elegantly structured."—Richard Fardon, Times Higher Education Supplement

"Compelling, insightful, rich in ethnographic detail, and worthy of becoming a classic in the scholarship on Africa."—Aidan Southall, African Studies Review

"Stoller brilliantly recreates the reality of spirit presence; hosts are what they mediate, and spirits become flesh and blood in the 'fusion' with human existence. . . . An excellent demonstration of the benefits of a new genre of ethnographic writing. It expands our understanding of the harsh world of Songhay mediums and sorcerers."—Bruce Kapferer, American Ethnologist

"A vivid story that will appeal to a wide audience. . . . The voices of individual Songhay are evident and forceful throughout the story. . . . Like a painter, [Stoller] is concerned with the rich surface of things, with depicting images, evoking sensations, and enriching perceptions. . . . He has succeeded admirably." —Michael Lambek, American Anthropologist

"Events (ceremonies and life histories) are evoked in cinematic style. . . . [This book is] approachable and absorbing—it is well written, uncluttered by jargon and elegantly structured."—Richard Fardon, Times Higher Education Supplement

"Compelling, insightful, rich in ethnographic detail, and worthy of becoming a classic in the scholarship on Africa."—Aidan Southall, African Studies Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fusion of the Worlds by Paul Stoller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2010Print ISBN

9780226775456, 9780226775449eBook ISBN

9780226775494

1

LOOKING FOR SERCI

Clack! A sharp sound shattered the hot, dry air above Tillaberi. Another clack, followed by a roll and another clack-roll-clack, pulsed through the stagnant air. The sounds seemed to burst from the dune that overlooked the secondary school of the town of a thousand people, mostly Songhay-speaking, in the Republic of Niger.

The echoing staccato broke the sweaty boredom of a hot afternoon in the hottest town in one of the hottest countries in the world and, like a large hand, guided hearers up the dune to Adamu Jenitongo's compound to witness a possession ceremony.

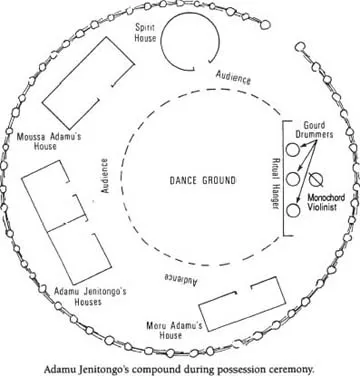

The compound's three-foot millet stalk fence enclosed Adamu Jenitongo's dwellings: four straw huts that looked like beehives. At the compound's threshold, the high-pitched whine of the monochord violin greeted me. Inside, I saw the three drummers seated under a canopy behind gourd drums. Although the canopy shielded them from the blistering Niger sun, sweat streamed down their faces. Their sleeveless tunics clung to their bodies; patches of salt had dried white on the surface of their black cotton garments. They continued their rolling beat. Seated behind them on a stool was the violinist, dressed in a red shirt that covered his knees. Despite the intensity of the heat and the noise of the crowd, his face remained expressionless as he made his instrument “cry.”

A few people milled around the canopy as I entered the compound, but no one began to dance. The clack-roll-clack of the drums ruffled the hot Sahelian air, drawing more people to the compound of Adamu Jenitongo, the zima or possession priest of Tillaberi.

When the sun marked midafternoon and the shadows stretched from the canopy toward Adamu Jenitongo's grass huts at the eastern end of his circular living space, streams of men and women flowed into the compound. Many of the woman wore bright Dutch Wax print outfits—bright red flowers, deep green squares contrasting with beige, brown, and powder-blue backgrounds. Many of the men wore white, blue, and yellow damask boubous—spacious robes covering matching loose shirts and baggy drawstring trousers. Vendors with trays of goods balanced on their heads were right behind the spectators. They sold cigarettes, hard candy, and chewing gum to the growing audience.

The music's tempo picked up; the buzz of the audience intensified. A number of young children danced in front of the musicians, but they were unnoticed by the swelling crowd and the possession troupe's major personalities. Adamu Jenitongo, the zima, remained far from the crowd, and the spirit mediums had not yet left the spirit hut—the conical grass dwelling in the easternmost space of the compound.

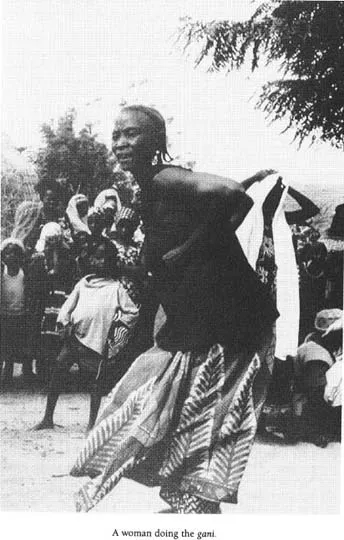

More people joined the audience. The relentless cries, clacks, and rolls of the music compelled three old women to dance; the crowd cheered. They sauntered onto the dance ground, grinning at one another. The loose flesh of their furrowed faces flapped as they danced.

Three movements distinguished their dancing. At the outset when the beat was slow, they danced in a circle. Moving counterclockwise to the slow beat, they kept their arms at their sides. When they stepped forward they pressed their right feet into the sand three times. Eventually, the dancers broke their circle to form a line at the edge of the dance ground in preparation for the second dance movement. The musicians quickened the tempo, and each woman danced forward toward the source of sound—the ritual canopy. They came closer and closer. The tempo raced toward its climax. Just in front of the canopy, the dancers furiously kicked sand. The musicians slowed the tempo, signaling the third dance movement. The dancers remained just in front of the canopy, moving only their heads and arms to the music. They turned their heads to the left while sliding their right hands along their right thighs. Then they slid their left hands along their left thighs, shaking their heads to the right. The musicians played and the dancers shook their heads from left to right, left to right. Beads of glistening sweat sprayed into the air.

One gifted dancer, an older woman with a face puckered by the sun, delighted the crowd with her graceful pirouettes followed by her clumsy bumps and grinds. Her performance so inspired a member of the audience that he broached the dance ground and gave her a five hundred franc note (about $2). The dancer took the money, held it high above her head, ran over to the canopy, and gave the note to one of the drummers, who put it into a common kitty. Even so early in the afternoon, the excitement of the music had generated a healthy pot.

The music swept the old possession priest onto the dance ground. Prompted by the dancing of his colleagues, Adamu Jenitongo, a slight, short man whose ebony skin stretched across his face like sun-weathered leather, matched the musicians’ frenetic pace. He glided toward the canopy, his sharp eyes transfixed on the violinist. Someone gave him a cane. He held it above his head and danced furiously. Concerned that the dancing could strain his old heart, his sister, Kedibo, whisked him from the dance ground. Despite its brevity, the old zima's vigorous performance elicited generous contributions to the kitty.

Soon after Adamu Jenitongo's turn, one of the old women dancers shooed the children from the dance area. Now the dancing was limited to those men and women who were part of the Tillaberi possession troupe. The musicians played the music of the White Spirits, the deities who resolve social disputes and offer advice to people who are about to change their lives. The leader of the mediums, Gusabu, strolled into the dance area accompanied by two of her “sisters.” They circled counterclockwise.

The musicians struck up the theme of one particular White Spirit, Serci, “the chief”. A praise-singer chanted:

Dungunda's husband. Garo Garo's husband.

Zaaje. White salt. Master of evil.

You have put us

Within your own covering of clouds.

Mercy and Grace.

Only God is greater than he.

He is in your hands.

He gave the angels their generosity.

You are the master of Kangey.

You brought the birth of language.

You brought about victory.

Zaaje. White salt. Master of evil.

You have put us

Within your own covering of clouds.

Mercy and Grace.

Only God is greater than he.

He is in your hands.

He gave the angels their generosity.

You are the master of Kangey.

You brought the birth of language.

You brought about victory.

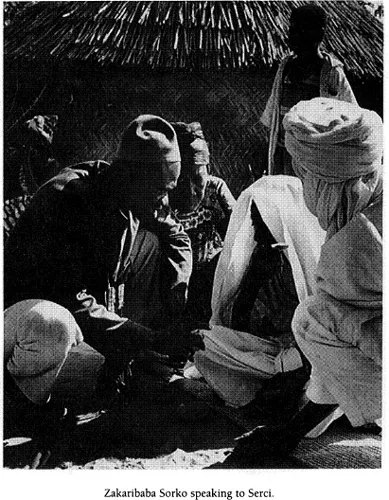

The drummers chanted the praise-poem repeatedly as they and the violinist held the audience in thrall with a syncopated profusion of clacks and rolls cut by the wail of the violin. The three mediums approached the musicians. Gusabu, a large woman with a fleshy face and watery eyes, took a further step toward the musicians. She swayed to the sounds in front of her, behind her. The praise-singer burst through the crowd, a torrent of poems pouring from his mouth. As Gusabu swayed, the sorko chanted praise-songs to the White Spirits and the Tooru (spirits controlling the natural forces of the universe—water, clouds, lightning, thunder). He juxtaposed his praise with the insult, “nya ngoko” (fuck your mother). “If the spirit does not respond to praise-poetry,” the sorko told me, “it will come to earth to demand retribution for my insults.”

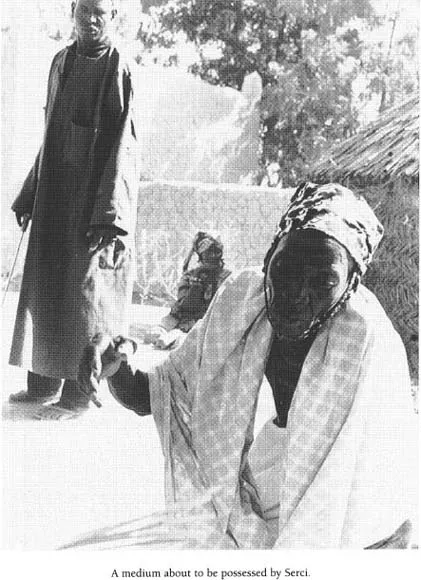

The musicians gradually quickened the tempo. Gusabu bobbed more rapidly now and shook her head back and forth, back and forth. Sensing that the spirit Serci was hovering just above the dance ground, the violinist upped the tempo even more. Gusabu twisted her body and pumped her arms; she perspired profusely. The sorko shouted directly into her ear. Serci was close now. Gusabu's forehead furrowed; she squinted. Tears streamed from her eyes and thick mucus flowed from her nose. Suddenly, Gusabu was thrown to the ground. She muttered, “Ah di, di, di, di, di, a dah, dah, dah, dah.” Groaning, she squatted on the sand, her hands on her massive hips.

Serci had arrived. The drummers welcomed him, chanting, “Kubeyni, Kubeyni. Dungunda Kurnya. Garo Garo Kurnya” (Welcome. Welcome. Dugunda's husband. Garo Garo's husband.).

The two women behind Gusabu guided Serci to the edge of the dance ground and seated the deity on a straw mat. Meanwhile, another woman, whirling in front of the canopy, obliged the musicians to pick up the pace. The sorko shouted into her ear, and she too was taken by Mahamane Surgu (Mahamane the Tuareg), which prompted Serci to leave his attending mediums and join Mahamane in the dance area. They hugged one another in greeting and then pointed at the musicians.

“Play good music,” they screamed.

The musicians responded, and the two spirits kicked, stomped, and grunted until the music momentarily died.

One of the attending mediums went to the spirit house to bring out the costumes. For Serci, the medium brought a white turban and white damask boubou, symbols of chiefly authority in Songhay. Mahamane Surgu was costumed in billowing black trousers and a long black boubou, both of which were made from thin Chinese cotton. A black turban was wrapped around Surgu's head—symbols of his Tuareg origin.

Preparations for this possession ceremony had begun several days before the musicians split the afternoon air in Tillaberi with their sacred sounds. Because Songhay marriages are full of uncertainties and often end in divorce, people contemplating marriage may seek the advice of the spirits. Plans for Serci's possession ceremony originated when the mother of a future groom visited Adamu Jenitongo.

“Zima,” she said to Adamu Jenitongo, “I am fearful of my son's marriage. Will my son be happy with his new wife? Will the woman bring me grandchildren?”

“You must protect yourself on the path,” the zima told her.

The woman nodded.

“We must stage a one-day White Spirit ceremony. We will look for Serci. Only Serci can answer these questions. Only Serci can tell you and your son how to protect yourselves.”

“Yes, Serci tells only the truth. We should have this ceremony, zima.”

“Good,” said Adamu Jenitongo. “Tomorrow bring me 2,500 CFA [roughly $10] and a white, a red, and a speckled chicken. We will hold the ceremony on a Thursday.” (Thursday is the sacred day of the spirits, a day they are likely to swoop down from the heavens.)

Now Adamu Jenitongo would once again exercise his authority as the impresario of the Tillaberi possession troupe. He summoned his grandson: “Habi, go to Gusabu's compound [the head of the Tillaberi mediums] and tell her about our news of the Serci ceremony.”

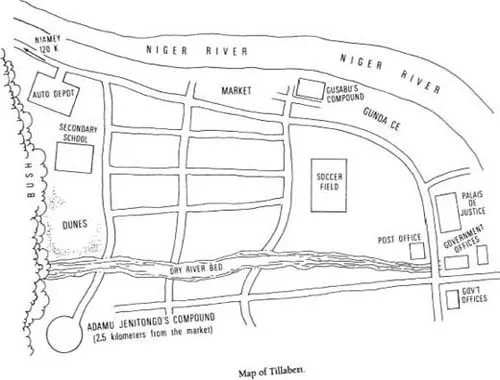

Adamu Jenitongo's grandson descended the dune on which his grandfather's compound perched. Marching through the deep sand, he came upon a dry riverbed strewn with the skeletons of cows and donkeys. He crossed the riverbed and climbed yet another dune, beyond which was the center of Tillaberi. As he reached the top of this second dune, he could see the Niger River stretching out before him. He walked toward the river on one of Tillaberi's wide dirt roads. He passed dry goods shops, parked trucks, a pharmacy, and a gas station. He crossed the single paved road of the town to pass the market and bus depot. Finally, as he came to the bank of the Niger, he arrived in Gusabu's neighborhood, Gunda Che.

Gusabu gave the boy water to drink in recognition of his long walk from the zima's compound. Like his colleagues in other villages, Adamu Jenitongo preferred to live close to the bush rather than in the center of town. “Near the bush,” Adamu Jenitongo often told me, “one has peace. One is far from the treachery of the town.”

Dressed in a black kaftan, Gusabu took another piece of black cloth and wrapped it around her head. Her brown-skinned brow was deeply furrowed and her eyebrows seemed perpetually raised as she assessed the zima's grandson. Fixing her watery eyes on the boy, she asked him questions about the upcoming possession ceremony.

“When is it to be staged?”

“They say Thursday,” the boy answered.

“Will it last more than one day?”

“They say it is a one-afternoon ceremony.”

“What is the purpose of the ceremony?”

“To bring Serci to Tillaberi.”

“How much will the mediums be paid?”

“My mother,” the boy protested, “I know nothing of money”

Gusabu was now ready to execute her plan of action. Calling to her own grandson, she asked the boy to go to the compounds of her associates to inform them about the scheduled possession ceremony. She herself would visit those mediums whose bodies alone could attract to earth the spirit Serci.

The next day, a full two days before the beginning of the festivities, a group of mediums trekked to Adamu Jenitongo's compound. Like the zima's grandson's journey the day before, the women's trip was like a march through time. They left their mudbrick compounds, which had neither electricity nor running water, and crossed a paved road. They walked past a secondary school, which, with its rows of one-story cement buildings, looked like a military base, and saw students who were dressed in European clothing. The students spoke French to one another. The women marched up the first of two dunes. Soon the moos of cows being led out to the bush overwhelmed the echoes of the French language. They passed through a cloud of dust raised by the cows and tramped across the dry riverbed. They climbed the second sand dune and caught their first glimpse of the zima's compound shimmering in the morning light. Behind them was the center of Tillaberi; ahead of them was the millet-stalk fence of Adamu Jenitongo's compound, and beyond it was the sun-baked bush dotted with occasional thorn trees. They stopped at the opening of the compound, where Adamu Jenitongo greeted them enthusiastically.

“Hadjo and Jemma,” he called to his two wives, “bring out some straw mats for our guests. Put them under the tree.”

Gusabu objected, however. “No, no, no. We don't want the mats there. Put them next to the spirit house,” she ordered crisply.

Gusabu, Adamu Jenitongo, and the other mediums sat down to talk. Gusabu pointed to the canopy. “Is it ready?”

“Yes,” Adamu Jenitongo replied. “I sanctified it yesterday.”

“How much money will my mediums be paid?” Gusabu demanded.

In his usual soft voice Adamu Jenitongo explained, as he had a thousand times: “Sister, you know that the share of a medium depends on the size and generosity of the audience. Besides,” he said, “you know that the fees of the musicians have been getting dearer.”

“I don't care, brother. We want more money.”

“May God provide it,” Adamu Jenitongo proclaimed.

“Amen,” the mediums responded. By now the lesser priests in Tillaberi, having heard the news about the scheduled possession ceremony, came to Adamu Jenitongo's compound to ask when it would begin. Meanwhile, apprentices to the lesser priests picked up debris and smoothed the sandy grounds of the compound with tree branches. The three drummers arrive...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- Acknowledgments

- Personae

- 1 Looking for Serci

- Part One: Organization of the Possession Troupe

- Part Two: Theaters of Songhay Experience

- Part Three: Possession in a Changing World

- Epilogue: Fusion of the Worlds

- Notes

- Glossary

- References

- Index