eBook - ePub

Divas in the Convent

Nuns, Music, and Defiance in Seventeenth-Century Italy

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When eight-year-old Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana (1590–1662) entered one of the preeminent convents in Bologna in 1598, she had no idea what cloistered life had in store for her. Thanks to clandestine instruction from a local maestro di cappella—and despite the church hierarchy's vehement opposition to all convent music—Vizzana became the star of the convent, composing works so thoroughly modern and expressive that a recent critic described them as "historical treasures." But at the very moment when Vizzana's works appeared in 1623—she would be the only Bolognese nun ever to publish her music—extraordinary troubles beset her and her fellow nuns, as episcopal authorities arrived to investigate anonymous allegations of sisterly improprieties with male members of their order.

Craig A. Monson retells the story of Vizzana and the nuns of Santa Cristina to elucidate the role that music played in the lives of these cloistered women. Gifted singers, instrumentalists, and composers, these nuns used music not only to forge links with the community beyond convent walls, but also to challenge and circumvent ecclesiastical authority. Monson explains how the sisters of Santa Cristina—refusing to accept what the church hierarchy called God's will and what the nuns perceived as a besmirching of their honor—fought back with words and music, and when these proved futile, with bricks, roof tiles, and stones. These women defied one Bolognese archbishop after another, cardinals in Rome, and even the pope himself, until threats of excommunication and abandonment by their families brought them to their knees twenty-five years later. By then, Santa Cristina's imaginative but frail composer literally had been driven mad by the conflict.

Monson's fascinating narrative relies heavily on the words of its various protagonists, on both sides of the cloister wall, who emerge vividly as imaginative, independent-minded, and not always sympathetic figures. In restoring the musically gifted Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana to history, Monson introduces readers to the full range of captivating characters who played their parts in seventeenth-century convent life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Divas in the Convent by Craig A. Monson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Italian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Donna Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana of Santa Cristina della Fondazza

In 1598, probably in late spring or early summer, two little girls left the world to enter the convent of Santa Cristina della Fondazza in Bologna. We don’t know the exact date, but documents tell us that their mother, Isabetta Bombacci Vizzana,1 had died on 19 April of that year. The following November their father, Ludovico Vizzani, loaned the convent a sizable sum, most likely to secure places for the girls. The older girl, Verginia, had recently turned eleven; the younger, Lucrezia, was barely eight.

At such a tender age, Lucrezia had no idea about what the future held for her, let alone that she might become an accomplished musician. But, out of more than 150 women musicians rediscovered in Bolognese convent archives in recent years, Lucrezia would be the only one whose compositions would find their way into print. Her Componimenti musicali de motetti concertati a una e più voci (Musical compositions in the form of motets in consort for one or more voices), published in Venice in 1623, assured her a modest renown in her day. She has not quite been forgotten in our own, even if the definitive modern dictionary of music managed to get her name wrong as recently as the 1980s. When in 2001 she made it into the standard college music history textbook, Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana achieved “real composer” status.2

Like most nuns of her time, Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana long remained little more than a name to us. Although the seventeenth-century Bolognese historian Gasparo Bombacci carefully set down the exemplary life of his and Lucrezia’s aunt Flaminia Bombacci of Santa Cristina (Bologna’s only Benedictine nun to have died “in odor of sanctity” before 1650), he makes no mention at all of his distinguished musical cousin, Lucrezia. By contrast, an elegantly decorated necrology from Santa Cristina, now lost, which extolled both the pious ends of sisters who achieved “good deaths” and others’ artistic and intellectual accomplishments, afforded its longest encomium—longer even than Flaminia Bombacci’s—to Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana.3 Perhaps among her sisters in religion Lucrezia’s star burned a little brighter than elsewhere in the world because they were the audience who knew her work first and best.

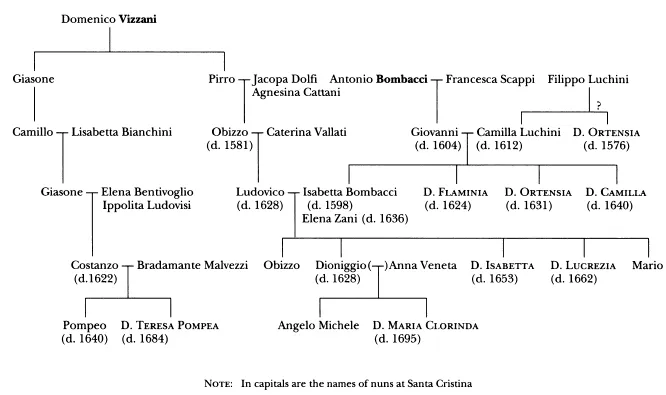

We can only piece together Lucrezia Vizzana’s life from scattered scraps of information. Her father, Ludovico di Obizzo Vizzani, hailed from an old, distinguished family, active in the city since the 1200s (see fig. 1). Various Vizzani distinguished themselves on the battlefield, in scholarship, or in the church. Carlo Emanuele di Camillo Vizzani, Lucrezia’s distant cousin, became rector of the Sapienza in Rome (now Sapienza—Università di Roma) in the mid-seventeenth century, for example, and inaugurated the Vatican Library in its modern form.

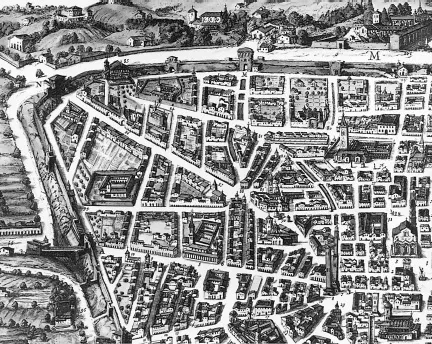

Since the late 1300s the family had lived on via Santo Stefano, not very far from the convent of Santa Cristina, at the site where in the 1550s and 1560s the imposing Palazzo Vizzani rose at via Santo Stefano 43 (fig. 2, near no. 87). This branch of the Vizzani line allied itself by marriage to the highest Bolognese elite: the Bentivogli, the Malvezzi, and the Ludovisi.

In the 1500s, Lucrezia’s father, Ludovico, and his less preeminent branch of the family lived farther downtown, near the corner of modern via d’Azeglio and via de’ Carbonesi, south of the basilica of San Petronio (fig. 2, no. 3). Even so, Ludovico’s father had been illustrious enough to merit interment in an extravagant, pyramidal tomb raised on marble columns (fig. 2, visible to the left of no. 76, between the two columns), which still draws tourists to Piazza San Domenico outside the basilica of the same name. Though Ludovico’s brother served a term among the anziani (aldermen), who administered the city, as his father and grandfather had done before him, Ludovico di Obizzo apparently achieved no such distinction and also goes unmentioned in Pompeo Dolfi’s “Who’s Who” of the Bolognese élite, Cronologia delle famiglie nobili di Bologna (Chronology of the noble families of Bologna; 1670).4

Given his less elevated position within the Vizzani clan, Ludovico Vizzani could not expect to find a wife among the Bentivogli, Malvezzi, or Ludovisi. His future wife, Isabetta di Giovanni Bombacci, came from an upwardly mobile family of slightly lower patrician status locally than her future husband’s. The marriage contract describes Isabetta’s father as mercator (merchant), the lowest of the city’s three governing ranks. Despite Gasparo Bombacci’s special pleading in his family history that “in Bologna trading still remains highly honorable and has been practiced by nobles without losing their claim of nobility,” we may safely assume that these Bombacci represented the sort of family to which more illustrious Vizzani than Ludovico were unlikely to turn at that period “if not for reasons of wealth or love,” as a seventeenth-century Bolognese social commentator put it.5 All the same, the Bombacci traced deep and ancient roots within the Venetian nobility and maintained venerable links to the Camaldolese order, for whom they had helped to build the Monastery of San Michele di Murano in the Venetian Lagoon. Isabetta’s father, Giovanni di Antonio Bombacci, had achieved greater civic distinction than his future son-in-law would ever manage, for he served among the gonfalonieri del popolo (people’s standard bearers), who represented Bolognese society’s lower ranks, and later in his life among the anziani, where Ludovico’s brother also served.6

FIGURE 1. The Vizzani and Bombacci Families (abbreviated)

Isabetta Bombacci, born in 1560, was the eldest survivor among Giovanni Bombacci and Camilla Luchini’s twelve daughters. Such an impressive brood was not extraordinary for upper-class Italian families. Isabetta’s paternal great-grandmother, for instance, had borne no fewer than twenty-four children, who (just as amazing and perhaps more so) had all lived past infancy. The fates of Isabetta and her eleven sisters were more typical for sixteenth-century families. Half died within two days to three years. At age twenty-seven, one married rather late and quite modestly but soon died in childbirth. By then Isabetta Bombacci had also married; after bearing at least five children, she expired before age forty. Isabetta’s four remaining sisters all became nuns, three at the convent of Santa Cristina—where the trio outlived all their other siblings by ten to thirty years.7

FIGURE 2. Detail of the eastern quarter of Bologna, showing Santa Cristina c. 1590. After Joan Blaeu, Theatrum civitatum et admirandorum Italiae (Amsterdam, 1663). Reproduced with permission of the Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio, Bologna. A = Porta and strada Maggiore; N = Porta and strada Santo Stefano; no. 93 = Santa Cristina; near no. 87 = Palazzo Vizzani; no. 5 = Santa Maria dei Servi; no. 3 = basilica of San Petronio; no. 38 = cathedral of San Pietro; no. 76 = San Domenico.

On 12 May 1581 Ludovico Vizzani and Giovanni Bombacci agreed to Isabetta’s dowry, most of which was to be invested in Bologna’s thriving silk trade. Although the Bombacci were active in banking and finance, some of their money came from the silk business, as their name suggests (bombice, “silkworm grub”). Ludovico and Isabetta’s marriage was recorded on 19 October 1581 in the Bombacci family’s parish church.8

Their first son arrived within a year but must have died in infancy or early childhood since he promptly disappears from the written record. After a fourteen-month respite, Isabetta was pregnant again. Dionigio was born in 1584. A third son, Mario, followed much later, in 1593. We know that he lived long enough to witness his mother’s death, but he followed her to the grave not long thereafter (no record testifies to exactly when). By 1593 Isabetta had also borne two girls. Verginia arrived in March 1587. Lucrezia, the future composer, entered the world three years later, on 3 July 1590.9

Verginia and Lucrezia later claimed to have lived in the convent of Santa Cristina della Fondazza since earliest childhood. Lucrezia’s convent memorial confirms that she sought refuge there “at an age when she thereby avoided the world’s swelling tides and sandbanks” (presumably a refined way of suggesting a time before puberty).10 Only a little over five minutes’ brisk walk from their maternal grandparents’ home on strada Maggiore—but quite a long way from their father’s house—Santa Cristina was the obvious choice for offspring of the Bombacci family.

Having entered Santa Cristina in early childhood, Lucrezia Vizzana scarcely knew the wider world beyond the convent wall, and not at all as an adult. Yet, as constricted as the monastic world she had entered might have been, it was eminently one of the best of all possible worlds of its sort in Bologna. By the early 1600s Santa Cristina, the second-oldest female house of the Camaldolese order (a relatively recent branch of contemplative Benedictines), had become one of the wealthiest, most exclusive, and most artistically distinguished of Bologna’s monasteries for women. In 1574 its yearly income had tied for fourth place among the diocese’s twenty-eight convents. By 1614, when its social and political fortunes had begun to decline, Santa Cristina still ranked a very respectable sixth.11 Catering to Bolognese noble and patrician families, Santa Cristina hovered above the reach of what the nuns called “ordinary” women. Members of the community tended to call each other donna (lady) or, for the most senior nuns, madre donna, rather than suora (sister, a name reserved at Santa Cristina for the servant nuns). They referred to the convent as the collegio rather than as the monastero. Some aspired as much, perhaps, to arts and letters as to religious life or, at the very least, saw nothing incongruous about intermingling arts and religion, exactly as various male members of their order had done for centuries. (Perhaps the most obvious examples are Guido of Arezzo in music, Lorenzo Monaco in art, and Niccola Malermi, first translator of the Bible into Italian.)

In convents of that time, a separate class of servant nuns known as converse looked after the governing class of professed nuns, thereby leaving the latter free to pursue the higher callings of prayer, contemplation, and chapel. The servant class usually comprised simple, illiterate country girls, who came to the convent with much smaller dowries than future professed nuns. The converse had no serious chapel responsibilities and no voice in convent government. They performed all the menial tasks within the convent—cleaning, cooking, gardening, tending the animals. In addition, each saw to the personal needs of a few professe, or professed nuns—much of the time, the three Bombacci sisters at Santa Cristina shared a single conversa with just one other professa. For a community theoretically governed by a vow of poverty, the extent of individual attention lavished on each of the professe would eventually strike ecclesiastical authorities of the 1620s as inappropriately luxurious.12 But in 1598, when Lucrezia Vizzana entered Santa Cristina, the convent’s opulent style of monasticism had yet to catch their attention.

Despite their mother’s recent death and their father’s virtually abandoning them at the convent gate, the little girls may have felt less forsaken than we might imagine. By 1598 the Bombacci had established such strong ties at Santa Cristina that the girls’ arrival there seemed inevitable. Three Bombacci aunts were already waiting there to receive them. Flaminia Bombacci had been accepted in 1578, Ortensia in 1580, and Camilla in 1588. Verginia and Lucrezia’s acceptance and socialization at the convent were thus due primarily to matrilineal connections. Flaminia and Camilla Bombacci would become the convent’s spiritual and political leaders of the 1620s.

Ranging in age from twenty-seven to thirty-five, these three maternal aunts, whom the little girls had probably visited since babyhood in frequent company with their mother, very likely cared almost maternally for the orphaned girls and perhaps doted upon them. In any case we know more generally that the reassurance and encouragement of sympathetic aunts commonly served as a gentle form of persuasion at the same time that it may have figured as something of an antidote to the socially forced confinement of an extraordinary percentage of upper-class girls of the day in convents. Although the Council of Trent had forbidden parents to force their daughters to become nuns and required bishops to be sure that every girl entered of her own free will, families developed subtle, effective means of encouragement. The typical practice of depositing the very young in the care of cloistered relatives ensured that after such an early entry into the cloister, by the time their sojourn there became permanent it would seem like the “natural” order of things for these girls. They would scarcely have had time to learn about the other meager options life might have offered them beyond the cloister’s arcades. As history would have it, the Vizzani girls were in fact among the last children accepted for education by close relatives at Santa Cristina, because the church hierarchy would explicitly prohibit this time-honored practice at the conv...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface to the New Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Dramatis Personae

- List of Abbreviations

- Praeludium: Putting Nun Musicians in Their Place

- 1 Donna Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana of Santa Cristina della Fondazza

- 2 Lucrezia Vizzana’s Musical Apprenticeship

- 3 Musical and Monastic Disobedience in Vizzana’s Componimenti musicali

- 4 Hearing Lucrezia Vizzana’s Voice

- 5 Troubles in an Earthly Paradise: “It Began because of Music”

- 6 Voices of Discord at Santa Cristina

- 7 Losing Battles with a Bishop: “We Cared for Babylon, and She Is Not Healed”

- 8 A Gentler Means to a Bitter End

- 9 “Pomp Indecent for Religious Observance and Modesty”

- 10 Another Bishop, Another Battle, a Different Outcome

- 11 A Last Battle and an Uneasy Peace

- Coda

- Notes

- Glossary

- Further Reading and Listening

- Index