- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Like Andy Warhol

About this book

Scholarly considerations of Andy Warhol abound, including very fine catalogues raisonné, notable biographies, and essays in various exhibition catalogues and anthologies. But nowhere is there an in-depth scholarly examination of Warhol's oeuvre as a whole—until now.

Jonathan Flatley's Like Andy Warhol is a revelatory look at the artist's likeness-producing practices, not only reflected in his famous Campbell's soup cans and Marilyn Monroe silkscreens but across Warhol's whole range of interests including movies, drag queens, boredom, and his sprawling collections. Flatley shows us that Warhol's art is an illustration of the artist's own talent for "liking." He argues that there is in Warhol's productions a utopian impulse, an attempt to imagine new, queer forms of emotional attachment and affiliation, and to transform the world into a place where these forms find a new home. Like Andy Warhol is not just the best full-length critical study of Warhol in print, it is also an instant classic of queer theory.

Jonathan Flatley's Like Andy Warhol is a revelatory look at the artist's likeness-producing practices, not only reflected in his famous Campbell's soup cans and Marilyn Monroe silkscreens but across Warhol's whole range of interests including movies, drag queens, boredom, and his sprawling collections. Flatley shows us that Warhol's art is an illustration of the artist's own talent for "liking." He argues that there is in Warhol's productions a utopian impulse, an attempt to imagine new, queer forms of emotional attachment and affiliation, and to transform the world into a place where these forms find a new home. Like Andy Warhol is not just the best full-length critical study of Warhol in print, it is also an instant classic of queer theory.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Collecting and Collectivity

At bottom, we may say, the collector lives a piece of dream life. For in the dream, too, the rhythm of perception and experience is altered in such a way that everything—even the seemingly most neutral—comes to strike us; everything concerns us.

Walter Benjamin, “The Collector”1

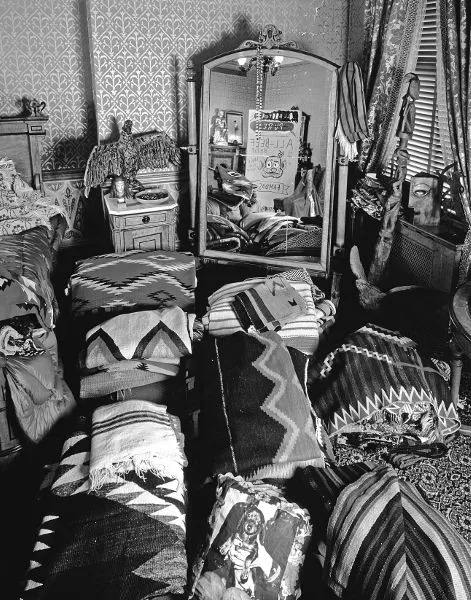

There may be no more vivid illustration of Warhol’s talent for “liking things” than his energetic and far-ranging collecting practices.2 An examination of the six-volume catalog of possessions sold at auction after his death reveals an astounding array of collections.3 One finds Art Deco furniture and silver; Native American blankets, rugs, and baskets; nineteenth-century Americana and folk art (some of which had been exhibited in the 1977 Folk and Funk exhibition); jewels, jewelry, and watches; and an art collection that included works by European modernists such as Duchamp, Klee, and Man Ray, as well as Warhol’s contemporaries Arman, Johns, Lichtenstein, Twombly, and Rauschenberg. As one looks through the 3,436 lots and sees the hundreds of watches and hundreds of chairs, the cookie jars, the busts of Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon, the ray-gun toys, the Josef Hoffman furniture and Puiforcat tea sets, the Russel Wright dishes and Navajo bracelets, it is not hard to believe that, as several accounts attest, Warhol went shopping for items to add to his collections every day.4

1.1 Norman McGrath, interior of Andy Warhol’s house during preparations for the Sotheby’s auction of his collections, 1988. Courtesy of Norman McGrath Photos.

Fred Hughes, Warhol’s friend and business manager, notes that he had been spending more than a million dollars a year just at auctions.5 He was not only an “indefatigable accumulator,”6 but an indiscriminate one (as press coverage of the auction sometimes disapprovingly opined): he was “interested in everything,” as Vito Giallo noted.7 While his dedication to collecting may have increased as he got older (and had more money to spend), it appears that collecting was a lifelong passion, a habit that Warhol developed in childhood, starting probably with film magazines and celebrity memorabilia.8

1.2 Norman McGrath, interior of Andy Warhol’s house during preparations for the Sotheby’s auction of his collections, 1988. Courtesy of Normal McGrath Photos.

Warhol’s collecting practices were by no means limited to “collectible” items—things that other people collect, creating a market—or even to the realm of purchases. His interest extended to encompass vast collections of photographs (his own and others’), thousands of hours of tape recordings he made with his Norelco tape recorder (which he called his “wife”), an array of perfumes, and his 612 Time Capsules, the boxes he filled with printed matter and whatever else he wanted to save that had no other collection to welcome it.9 It appears Warhol strove to have a collector’s relationship with as many objects of perception, across the senses, as he possibly could, as a matter of general principle and daily habit.

Warhol’s artwork is a record and a map of this habit. For instance, his practice of tape recording all of his social interactions gave him the idea for A: A Novel, which was to be a transcript of twenty-four hours of taped conversations with his friend Ondine. And when one looks through Warhol’s photo collections, one sees the images that formed the basis of his best-known paintings: press photos of car crashes and suicides, the New York City Police Department’s Thirteen Most Wanted Men pamphlet, and endless celebrity photos, including scores of Marilyn Monroe publicity shots.10 Collecting was the condition of possibility for Warhol’s appropriative painting practice. But Warhol’s collections are not only the “source material” for his paintings (and other works); they are also their model. After a photo has been selected from the array of Marilyn photos, for example, the image of her face rejoins a group of others, similar yet distinctly imperfect, within the space of the canvas itself, creating a new collection there. Indeed, the logic of the collection seems to permeate Warhol’s aesthetic practices. But what, precisely, is that logic, and what is its appeal?

Walter Benjamin suggests that the collector is motivated by a desire to establish an intimate relationship to the material world, one that could find a home within an economy oriented around consumption but that nonetheless sidesteps capitalist relations to private property. Where (par Marx) “private property has made us so stupid and one-sided that an object is only ours when we have it—when it exists for us as capital, or when it is directly possessed, eaten, drunk, worn, inhabited, etc.,—in short, when it is used by us,” the collector relates to objects neither as capital nor in terms of use.11 Indeed, the collector’s first move is to “[detach] the object from its original functional relations.”12 Collecting “entails [not only] the liberation of things from the drudgery of being useful” but their transference into a “magic circle” where they can associate with other things that are like them.13 The collector “brings together what belongs together,” creating collectivities of objects based on relations of resemblance.14

Being a collector allowed Warhol to ask of each object of perception, What collection does this belong to? This had the salutary function of reorienting perception toward the “active mimetic force acting expressly inside things” (SW2, 684). On a daily basis, relating to the world as a collector amplified the similarities and commonalities in any thing he encountered. This may have permitted Warhol’s liking to “transfer” from old objects onto new ones along the paths established by likeness.15 To the extent that each like is a “new edition or facsimile,” as Freud puts it, of earlier likes, such that we never like anything for the first time, the very act of liking assembles, as it moves through the world, a collection. Relating to the world as a “collector,” then, is a way to amplify this aspect of everyday activity and be certain that liking always has multiple itineraries along which to travel.16 For the collector, Benjamin notes, “the rhythm of perception and experience is altered in such a way that everything—even the seemingly most neutral—comes to strike us; everything concerns us.”17 In short, collecting was one of Warhol’s chief strategies for attuning to similarities and thereby maximizing his capacity for being affected.

If being a collector alters the rhythm of perception and experience so that the patterns of similarity are amplified as one moves through the world, that rhythm is punctuated by the moments when one adds a new object to a collection. The “pleasure of collecting was the act of acquisition,” Warhol’s friend and colleague Rupert Smith observed, because that is the moment when the collector initiates something or someone into a new existence as a like-being among other like-beings, in a collective space defined by the mutual, nonhierarchical relations of resemblance.18 There, it experiences a “rebirth,” leaving behind its former identity from the everyday world of means-ends rationality and commodity fetishism, entering a territory where it is possible for other “likenesses [to befriend] one another.”19

Within the collection, the object is involved in a process of varied and variable belonging and becoming. Not only is each new acquisition transformed as it achieves its significance in relation to the collection; it also slightly reorders the collection as a whole, transforming every other item by changing the composition of the group. Because the totality defined by the collection changes with each item added to it (like T. S. Eliot’s “tradition,” modified by the addition of each new work of literature), there is no Platonic type, no ideal chair or ideal teapot, hovering over Warhol’s various collections and bringing them to coherence.20 Instead, we might say that collecting is a practice for creating a space of commonality shared by all the objects in the collection, constantly changed by the relations of resemblance they participate in.

The collection is “used” in the sense that it is a device that allows one to relate to the everyday world of objects in terms of their similarities and correspondences. Without the collection, there would be no place for collected objects to be initiated into a group existence. It may have been partly for this reason that Warhol had no intention of ever “cashing in” on his purchases, even though he excelled at finding bargains or “sleepers” and took pleasure in speculating about the future value of his acquisitions. Suzie Frankfurt, a friend of Warhol’s since the 1950s, remarked that, “as for trading or selling—never, never, never. He believed in holding onto everything, squirreling it all away.”21

Unlike many collectors, Warhol was not interested in the display of his collections.22 He kept his collecting private; it was, as his boyfriend Jed Johnson described it, “inconspicuous consumption.”23 (Warhol reportedly regretted displaying his collection of folk art in Folk and Funk, and seemed to stop collecting in this area after the exhibition.24) His purchases eventually transformed his townhouse, which had been carefully and beautifully designed by Johnson, into storage space for unopened boxes, stacks, and assemblages of objects alongside and underneath unemptied shopping bags. Although objects did not have to be physically organized into their collections in order to belong to them, Warhol liked to remind himself of their existence. “He kept most of the rooms locked,” Johnson observes. “He had a routine. He’d walk through the house every morning before he left, open the door of each room with a key, peer in, and then relock it. Then at night when he came home he would unlock each door, turn the light on, peer in, lock up, and go to bed.”25 The purpose of the ritual tour was not to pore over the collections, or organize or sort them; nor, I think, was it to luxuriate in the pleasure of possession or ownership as such. Rather, I think this routine reassured Warhol of the presence of this vital and renewable resource, which gave him access to the tremors of becoming and belonging that accompanied each new acquisition.

1.3 Steven Bluttal, interior of Andy Warhol’s house, 1987. Collection of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

This belonging and becoming was all the more attractive to the extent that Warhol could imagine his own participation in it. In stimulating his “gift for seeing similarity,” his visits with his collections may have also reminded him of the mimetic centers dwelling in everything and everybody, including himself. The sociality and conviviality Warhol felt in the collection was a resource and a model. Its powers radiated outward, inviting others into its orbit. Fred Hughes, for instance, writes that their shared enthusiasm for collecting formed “one of the chief sources of our friendship and collaboration.”26 Warhol liked to like together.

1.4 Steven Bluttal, interior of Andy Warhol’s house, 1987. Collection of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

In Warhol’s imaginative identification with his like-beings, focusing on the flawed or broken object, the one with signs of wear and use, may have been an aid. Such a preference, not typical among collectors, could be seen clearly in Folk and Funk, whose curators noted Warhol’s “taste for defects,” his attraction to “objects which are cracked, broken or somehow marred.”27 In Raid the Icebox, the 1970 exhibition Warhol curated from the storage areas of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art, he chose damaged or overlooked items such as a warped table, Windsor chairs that had been kept for spare parts, and storage cabinets filled with old shoes.28 Traces of use are one of the aspects of the object that draw what Benjamin calls the collector’s “physiognomic” interest.29 Such an interest, an attempt to “read into” the object, to tell its “biography” and predict its fate, stimulates a mimetic attempt to relate to the world from the point of view of the object. Moreover, these signs of wear or flaws, like the mistakes that were part of the silkscreen process (a similarity noted also by the curators of Folk and Funk), indicate a way in which these objects fail to match up to their type or model. Like Warhol and his friends, the worn, imperfect, and marred objects in Warhol’s collections misfit together.

As I have suggested, Warhol’s paintings are themselves often organized as collections, and in several ways. At the beginning of his pop career he often repeated images on a single canvas, in compositions like Marilyn × 100, 25 Colored Marilyns, Thirty Are Better Than One (images of Mona Lisa), 210 Coca-Cola Bottles, or Black and White Disaster #4. These paintings, which the Catalogue Raisonné calls “serial compositions,” contained a fixed number of images on a single canvas. Beginning with his first commissioned portrait, Ethel Scull 36 Times (196...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Like

- 1 Collecting and Collectivity

- 2 Art Machine

- 3 Allegories of Boredom

- 4 Skin Problems

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Index

- Footnotes

- Plates

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Like Andy Warhol by Jonathan Flatley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Arte general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.