![]()

1

REWRITING HISTORY IN STONE

In order to understand monuments of any kind, it is important to grasp the intentions and motivations of those who sought to erect a monument in the first place. This holds true for Confederate monuments, which have dominated the southern landscape for more than 150 years. They were placed there by white southerners whose intentions were not to preserve history but to glorify a heritage that did not resemble historical facts. By erecting these statues, white southerners have, over time, upheld a past in which the ideals of Confederate nationalism rest on metaphorical pedestals of heroism and sacrifice, while at the same time they negate the legacy of slavery and suggest that all white southerners were committed to the Confederate cause, which they were not.1

Over time, monument supporters concocted new language to defend the South’s monuments or to employ them in the defense of the region itself. In the 1950s, the Confederate tradition expanded to include Cold War rhetoric that warned southern whites that the civil rights movement and federal intrusion were linked to communism. In the immediate post–civil rights era, words like “equality” were employed in the defense of monuments, while during the era of multiculturalism, supporters argued the need to protect “Confederate American” heritage. During the post-9/11 years, monument defenders likened removal to the Taliban’s destruction of cultural artifacts. The target kept shifting because the statues were not about history; rather, they symbolized something even more precious to the cause of white supremacy—protecting the southern way of life.

Consequently, it is not a stretch to argue that removing a monument is not removing history, at least not the history of the Confederacy. Rather, the real history of these statues and markers is about their impact as objects of reverence for many white southerners, though not all, and as painful reminders of slavery and Jim Crow for generations of black southerners. And, as historian Malinda Maynor Lowery has written, the history of Confederate monuments “also erase[s] Indians—as well as Asians, Middle Easterners, Latinos, and other diverse peoples who call the South home.”2 Understanding the fundamentals of that history is essential if communities are to make informed decisions about what to do with the statues in their midst. The ultimate purpose of the pages that follow is to provide the historical foundation that will allow readers to grasp where these monuments fit in the history of the post–Civil War South and all that came after.

To begin, monuments are not just pillars of stone without meaning; every monument also represents a system of beliefs. Nor are they purely static objects; the groups who erected them, whether ladies’ memorial associations, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, or the men’s organizations that have built the most recent ones, did not just put them up and walk away. Throughout their history, Confederate monuments became reanimated on an annual basis through rituals held on Confederate Memorial Day and on the birthdays of Confederate generals, during Civil War reenactments, and in the protests against their removal. There is also a distinction to be made between memorials and monuments. While memorials serve to commemorate the dead through a special day or in a public space, they are not monuments. On the other hand, monuments are always a type of memorial. For more than a century, white southerners have gathered around these memorials to recall the Confederate past and reassert their commitment to the values of their ancestors, the very same values that resulted in a war to defend slavery and expand the institution. Thus, whether they stand on courthouse lawns or in cemeteries, and regardless of the additional meanings they have taken on over the course of 150 years of history, Confederate statues have always been attached to the cause of slavery and white supremacy.

The connection between white supremacy and Confederate monuments is not an exaggeration or an after-the-fact revisionist interpretation. Confederate veterans openly used the term “Anglo-Saxon supremacy,” which today we simply refer to as white supremacy. It appeared repeatedly in unveiling speeches as a badge of honor for the men who helped reverse the gains made by freedmen during Reconstruction. The Ku Klux Klan and its first grand wizard, Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, were applauded for restoring racial order to the South through tactics of violence and intimidation against African Americans. In 1914 Laura Martin Rose, a UDC member from Mississippi, published a booklet on the KKK that was endorsed by both the UDC and the Sons of Confederate Veterans as a publication that should be placed in school libraries. She hoped that it would “inspire” white southern youth “with respect and admiration for the Confederate soldiers,” who, she wrote, “were the real Ku Klux.” These “sturdy white men of the South,” she declared, “maintained white supremacy and secured Caucasian civilization,” later adding that during Reconstruction their efforts helped “to maintain the supremacy of the white race.”3

Southern whites after the Civil War were overwhelmingly preoccupied with coming up with a narrative to explain their defeat. Any book about Confederate culture and its evolution following the Civil War, therefore, must begin with understanding how white southerners came to terms with that defeat, how they justified their failure to create a separate nation, and how they outright rejected the idea that slavery was a primary cause of the Civil War. To do so requires an examination of the evolving postwar narratives about the Old South, the Confederacy, and even Reconstruction—all of which revolve around what Confederates and their descendants called the “Lost Cause.”

White southerners were first aided in their efforts to explain not only what went wrong but also why their cause was just by Edward A. Pollard, the wartime journalist for the Richmond Examiner. In 1866 Pollard, a native Virginian, wrote a tome he titled The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates. A “new” southern history immediately suggested that this was intended as a partisan assessment of the war even as the first histories of the war were just being published. Over the course of 752 pages, Pollard laid out a Confederate account of the war as well as a narrative that proved useful to white southerners reeling from defeat and the devastation of their world. Not only did he coin the term “Lost Cause,” but he provided former Confederates with a rhetorical balm to soothe their psychological wounds. In doing so, he helped lay the foundation of a mythology that reassured them that their cause was just and their values worth fighting for even in the face of a thoroughly crushing defeat.4

Born into the planter class of Nelson County, Virginia, in 1832, Pollard grew up on a wealthy plantation worked by more than 100 slaves and was an ardent defender of the South’s “peculiar institution.” In 1859, when he was a young man of twenty-eight, he earned fame from the publication of Black Diamonds Gathered in the Darkey Homes of the South, a book in the form of a series of letters with David Clark, an attorney from Newburgh, New York, wherein Pollard offered a robust defense of slavery. Alongside romanticized portraits of the enslaved he personally knew growing up on his father’s plantation, Pollard’s letters rationalized keeping human beings enslaved while also offering a pointed critique of abolitionist writers like Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, whom he disparagingly referred to as “n****r worshippers.”5

Pollard wrote about the South from a position of class privilege. He grew up as a member of the slave-owning planter class and, because of the increasing pressure placed on that group by northern abolitionists, offered what became the standard defense of slavery then and, in some circles, even today. In effect, he argued for slavery’s “civilizing” influence. Writing to Clark from Virginia in 1858, he asserted, “The American institution of slavery does not depress the African but elevates him in the scale of social and religious human being.” Two pages later he repeats himself: “I think the remarkable characteristic of our ‘peculiar institution’ in improving the African race humanly, socially, and religiously, is alone sufficient to justify it.” Pollard’s use of the term “African” and “African race” was commonplace. It mattered not that for more than a century the expansion of slavery had resulted from natural increase, nor that the enslaved were no longer “African” in the truest sense of the word. By this time they were as Virginian as Pollard.6

Pollard’s ideas about slavery were in keeping with this vociferous defense of southern nationalism. Like other men of his class, he believed in the superiority of southern culture, economic self-sufficiency based on plantation slavery, and the desire for regional independence. The North’s form of capitalism, he argued, debased workers in the form of “wage slavery” and neglected their basic needs, unlike those slaves in the South who were fed, clothed, and cared for in their old age. The South, therefore, was the antithesis of what Pollard called the “garish” North. Further, white southerners were the true caretakers of the nation’s constitutional heritage. In effect, by every measure, the South was superior to the North.

The Confederate generation’s undying faith in southern nationalism and belief that southern culture was superior to that of the North made defeat a hard pill to swallow. The Lost Cause became Pollard’s paean to southern nationalism and a rally cry to not give up on it. The war might be over, but the fight to maintain the region’s values still existed. The fight for Confederate independence, according to Pollard and those who followed in his footsteps, was reinvented in order to align with the South’s postwar reality.

As a Lost Cause evangelist, Pollard gave future generations the language and arguments to defend white supremacy and dismiss slavery as a cause of war. That those of the Confederate generation were the rightful heirs of the Revolutionary generation was just one argument that played out repeatedly for decades, particularly the South’s defense of the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution, which preserves states’ rights. A second argument, a complete reinterpretation of southern nationalism, was that slavery had been necessary to preserve the racial status quo and prevent race war. Pollard and others still justified slavery as a paternalistic system that benefited the enslaved, but in the shadow of defeat, it now needed to be seen as necessary. This narrative allowed Confederate soldiers to be understood as defenders not of slavery but of the region and their race. In sum, these false memories of the Confederacy still had value, even in defeat. The Lost Cause, therefore, was nothing to lament. It was a “just cause,” and in the postwar South, white supremacy was front and center.7

Pollard stood firm in his conviction of the justness of the South’s cause. In the conclusion to his book on the war, he remained convinced of the superiority of Confederate soldiers and suggested that the war had proved nothing. “The Confederates have gone out of this war,” he wrote, “with the proud, secret, dangerous consciousness that they are THE BETTER MEN, and that there was nothing wanting but a change in a set of circumstances and a firmer resolve to make them victors.” That lack of resolve, for Pollard, fell directly on the shoulders of Jefferson Davis and his administration, not on the larger populace of the South.8 In effect, white southerners did not lose the war; their leaders failed them.

Pollard also argued that despite the war’s outcome, the South did not have to admit to defeat but rather only to what was “properly decided.” For him, only two issues were determined in 1865—the restoration of the Union and a legal end to slavery. “It did not decide negro equality; it did not decide negro suffrage; it did not decide State Rights … and these things which the war did not decide, the southern people still cling to,” he proclaimed. In this, Pollard was prophetic. White southerners absolutely held fast to the supremacy of their race and used it as a means to control the formerly enslaved, even in the face of Reconstruction.9

Reconstruction, the twelve-year period that followed the Civil War when it ended in 1865, sought to reunify the nation but also assist newly emancipated men and women with the transition from slavery to citizenship. It required the existence of federal troops and officials in the states of the former Confederacy to ensure that former Confederates complied with the changes to laws, including constitutional amendments that abolished slavery, made freedmen citizens, and gave black men the right to vote. Reconstruction also resulted in the creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau, run by federal officials, to support African Americans as they adapted to their freed status. For white southerners, who called Reconstruction the “Tragic Era,” these changes were an insult added to the injury of defeat and destruction throughout large swaths of the region.

Even before Pollard published The Lost Cause, southern states instituted “black codes” to control the movement of freed people, using older “vagrancy” laws to arrest and punish black men and women for being “idle” and forcing black children into “apprenticeships” with their former masters. Colonel Samuel Thomas, a Freedmen’s Bureau official assigned to Vicksburg, Mississippi, testified before Congress in 1865 that former Confederates “are yet unable to conceive of the Negro as possessing any rights at all.” As he further explained, “The whites esteem the blacks their property by natural right, and however much they may admit that the individual relations of masters and slaves have been destroyed by the war and the President’s emancipation proclamation, they still have an ingrained feeling that the blacks at large belong to the whites at large, and whenever opportunity serves they treat the colored people just as their profit, caprice or passion may dictate.”10 Reconstruction took on an added urgency because of testimony like Thomas’s, and Congress took action by ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, providing freedmen with citizenship, and the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, which provided for black male suffrage—the very rights that Pollard claimed the war had not decided.

White southerners never fully accepted former slaves as citizens, and once federal troops had completely withdrawn from the region in 1877, southern state legislatures immediately sought ways to reverse the rights Reconstruction had given them. Those efforts were ramped up in 1890 when Mississippi, led by one of its U.S. senators, James Z. George, ratified a new state constitution whose primary purpose was to disfranchise black male voters, reversing the rights afforded them by the Fifteenth Amendment. Known as the “Mississippi Plan,” it added a poll tax of two dollars to vote and what became popularly known as the “understanding clause” that required voters to be able to read any section of the state constitution or “be able to understand the same when read to him or give a reasonable interpretation thereof.” While these changes also affected poor whites, their primary target was black voters. Throughout the 1890s, other southern legislatures followed suit and changed their state constitutions to include a poll tax and an understanding clause.

By 1901, black men had effectively been disfranchised in all the states of the former Confederacy. Alongside these legal machinations, southern lawmakers were assisted in their efforts by vigilante groups like the Ku Klux Klan and other white men who used violence to intimidate black men and prevent them from voting. Together, they reclaimed the region under the hood of white supremacy, reversing the effects of the Reconstruction amendments intended to provide blacks meaningful citizenship.

These were the political and racial realities of the South as Confederate monuments were being built. White men enacted Jim Crow laws from their state legislatures, while in the streets they practiced “lynch law”—extralegal racial violence to bring African Americans into compliance. Eliminating black men from political office and reasserting control of the public square also had an unintended effect—it cleared the way for white women to assume a public role in the campaign of white supremacy through monument building.

■ ■ ■

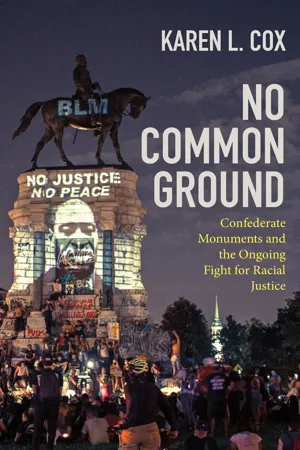

The earliest monuments were built in cemeteries as a means of honoring the Confederate dead who were buried there. That effort was begun by women who formed ladies’ memorial associations after the war. Their work continued and expanded after Reconstruction as statues started to appear outside of cemeteries and, in the 1890s, began to reshape the public landscape. The most famous example of this change was in Richmond, Virginia, where an enormous equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee was unveiled in May 1890. Lesser known monuments were also built throughout the South in parks and along boulevards and main streets.

The most common site for building Confederate monuments was on the grounds of local courthouses and state capitols, which today makes them the most controversial of all Confederate memorials. Often placed directly in front of the courthouse, these monuments have claimed the public square for southern whites, spaces that for more than a century have been not simply white-controlled but also shaped by segregation. Inside the courthouse or statehouse, white men made laws that served as a cudgel against African American equality, while outside, the Lost Cause narrative became ritualized through annual observations of Confederate Memorial Day.

Confederate commemorative activity helped reinforce another form of white supremacist messaging at courthouses and statehouses—racial violence. As Sherrilyn Ifill writes in her book, On the Courthouse Lawn, courthouses were “a deliberate choice of venue for lynchings.” While Ifill’s book is focused on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, her claim carries weight in other parts of the South where public spaces were “used to enforce the message of white supremacy, often violently.” Lynch mobs often overpowered local sheriffs, some of whom were complicit, removing black prisoners located in the jails adjacent to courthouses only to lynch them in front of the courthouse itself. As Ifill points out, these and other lynchings were not community secrets. Members of the local white community knew about them and were often complicit in these violent acts, which were frequently committed in public. Hundreds and sometimes thousands attended these spectacles.11

Those who argue that Confederate monuments are simply about heritage willfully ignore the historical and physical contexts in which they were built. It is nearly impossible to ascribe innocent veneration of the war dead to those who constructed Confederate monuments, especially during the rise of Jim Crow and racial violence. Building a monument to the Confederacy on grounds where laws were made or upheld, especially during the heyday of the UDC between the mid-1890s and World War I, symbolized more than paying homage to Confederate heroes. Courthouse lawns are supposed to be democratic public spaces, since they surround the building where citizens engage with their government. Given that, it is important to understand that statues were placed adjacent to courthouses with th...