- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

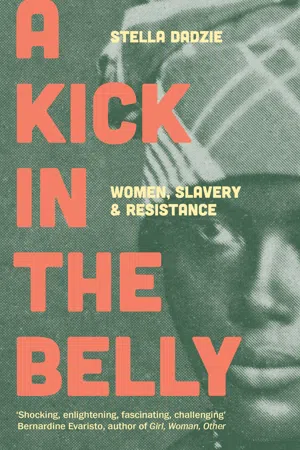

The forgotten history of women slaves and their struggle for liberation.

Enslaved West Indian women had few opportunities to record their stories for posterity. In this riveting work of historical reclamation, Stella Dadzie recovers the lives of women who played a vital role in developing a culture of slave resistance across the Caribbean.

Dadzie follows a savage trail from Elmina Castle in Ghana and the horrors of the Middle Passage, as slaves were transported across the Atlantic, to the sugar plantations of Jamaica and beyond. She reveals women who were central to slave rebellions and liberation. There are African queens, such as Amina, who led a 20,000-strong army. There is Mary Prince, sold at twelve years old, never to see her sisters or mother again. Asante Nanny the Maroon, the legendary obeah sorceress, who guided the rebel forces in the Blue Mountains during the First Maroon War.

Whether responding to the horrendous conditions of plantation life, the sadistic vagaries of their captors or the 'peculiar burdens of their sex', their collective sanity relied on a highly subversive adaptation of the values and cultures they smuggled from their lost homes. By sustaining or adapting remembered cultural practices, they ensured that the lives of chattel slaves retained both meaning and purpose. A Kick in the Belly makes clear that subtle acts of insubordination and conscious acts of rebellion came to undermine the very fabric of West Indian slavery.

Enslaved West Indian women had few opportunities to record their stories for posterity. In this riveting work of historical reclamation, Stella Dadzie recovers the lives of women who played a vital role in developing a culture of slave resistance across the Caribbean.

Dadzie follows a savage trail from Elmina Castle in Ghana and the horrors of the Middle Passage, as slaves were transported across the Atlantic, to the sugar plantations of Jamaica and beyond. She reveals women who were central to slave rebellions and liberation. There are African queens, such as Amina, who led a 20,000-strong army. There is Mary Prince, sold at twelve years old, never to see her sisters or mother again. Asante Nanny the Maroon, the legendary obeah sorceress, who guided the rebel forces in the Blue Mountains during the First Maroon War.

Whether responding to the horrendous conditions of plantation life, the sadistic vagaries of their captors or the 'peculiar burdens of their sex', their collective sanity relied on a highly subversive adaptation of the values and cultures they smuggled from their lost homes. By sustaining or adapting remembered cultural practices, they ensured that the lives of chattel slaves retained both meaning and purpose. A Kick in the Belly makes clear that subtle acts of insubordination and conscious acts of rebellion came to undermine the very fabric of West Indian slavery.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Kick in the Belly by Stella Dadzie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Global Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Terrible Crying:

Women and the Africa Trade

Women and the Africa Trade

There were many women who filled the air with heart-rending cries which could hardly be drowned by the drums.

Ship’s surgeon, 1693

There is no way to tell this horror story in a palatable way. Perhaps, if the descendants of those who benefited most had made recompense for this dark chapter in our shared history, it would be easier to talk about. But the legacies of those centuries of genocide and abuse are still with us, in relative levels of poverty and education, infant mortality and prison occupancy rates, wars, human suffering and a plethora of other glaring North-South inequalities, both social and economic, that cry out for reparation.

For all of this, it was never a straightforward black-white issue, and who owes what to whom is an ongoing debate. The trade in captured Africans was a complex transaction and Europeans were responsible for every aspect of its execution, yet the unpalatable truth is that it could never have survived or prospered without significant African involvement. But if some Africans colluded in the theft and sale of their own people, the evidence shows that there were also countless others who found the courage and the means to fight back, despite every effort to quash their human spirit.

This is the thought that preoccupies me as I step down into the dungeons of Elmina Castle in Ghana, Portugal’s first African trading fort. Built in 1482, it is an enduring monument to one of history’s most shameful epochs. In the holding cells, more than two centuries after Britain officially abolished the Atlantic slave trade, the stench of hundreds of thousands of captives still clings to the walls.

In the sun-scorched courtyard, a solitary cannonball too heavy to lift marks the start of our guided tour. Our guide describes how women who declined to ‘entertain’ their captors during the long months awaiting embarkation would be chained to the cannonball at the ankle or forced to hold it aloft in the blistering heat for hours at a time – a tantalising hint of the defiant mindset of those recently captured women. Inside the death cell, where mutinous soldiers and rebellious captives alike were left to rot, the atmosphere remains oppressive. Its door, marked with a skull and crossbones, acts like the lid of a coffin, blocking out light and air. Yet even this tomb-like cell speaks of dissent and rebellion – why else would it have existed?

A narrow, well-worn staircase leads us from the courtyard to the officers’ quarters above. The windows offer a panoramic view of the Atlantic Ocean, evoking a distant memory of slave ships of every nation anchored offshore, plying their ignominious trade. The governor’s breezy rooms contrast starkly with the suffocating gloom of the slave holes below, where the claw marks of the desperate and the dying are still visible above a dark, indelible tidemark of human waste. The horrors endured by hundreds of tightly packed captives receive graphic illustration when our guide points to the former site of huge ‘necessary tubs’ that would have been filled to the brim with excrement. A vile death by drowning awaited those unfortunate souls who, too exhausted to perch on the edge, slipped and fell in.

We stoop low to enter the cramped corridor that led countless men, women and children to step, bound and shackled, through the ‘door of no return’. The architecture tells its own story – a narrow, single-file opening, designed to frustrate all thoughts of escape as the captives were bundled into longboats that would ferry them to the waiting ships. Yet thoughts of escape there must have been, for a whole industry was developed to equip the traders with the heavy iron chains and shackles they needed in order to prevent it.

Back in the courtyard, we are almost blinded by the brilliant sunshine reflecting from a brass plaque in honour of the millions who perished. It reads: ‘In Everlasting Memory of the anguish of our ancestors. May those who died rest in peace. May those who return find their roots. May humanity never again perpetrate such injustice against humanity. We, the living, vow to uphold this’.

Fine words indeed.

Conditions such as those in Elmina would become commonplace as local chieftains became more and more complicit in the capture and sale of their own people. During the seventeenth century, their efforts to consolidate local or regional power came to depend increasingly on the exchange of prisoners of war and other hapless victims, both male and female, in return for guns and sought-after European commodities. The result was a highly lucrative partnership – one that has survived to this day in the corrupt dealings between the power brokers of Africa and Europe.

As people-trade entrenched itself along the West African coast as far south as the Congo and Angola, those intrepid Portuguese, Danish, Dutch, French and English traders, many of whom built their own forts and trading posts, could rely on a steady supply of captives from the interior to fill the waiting barracoons – the end result of a complex process of barter and exchange of ‘equivalent’ goods in return for captured humans. Increasingly, African lives came to be valued in beads, cloth, gunpowder, rum and iron bars.

Not all chiefs took so readily to the sale of their own people. Particularly in the early years of the trade, when the slavers’ success relied heavily on the patronage of local rulers, some chiefs bucked the trend and resisted all involvement. Africa, like Europe, was no more than a vague geographical concept at the time. In reality, Europe’s slave traders encountered a complex array of kingdoms and tribes, some more sophisticated than others, with competing interests, language barriers, social and cultural differences, rivalries and territorial ambitions, as well as widely differing attitudes to slavery. Inevitably they met with powerful Africans who wanted a piece of the action. But they also found others who were vehemently opposed the trade, including some impressive African women.

As early as 1701, the Royal African Company was writing to its factors at Cape Coast castle to alert them to the dangers of local resistance, led by a woman who clearly wielded considerable power in her own right:

We are informed of a Negro Woman that has some influence in the country, and employs it always against our Influence, one Taggeba; this you must inspect and prevent in the best Methods you can and least Expense.1

Taggeba was one of several powerful African women who resisted European encroachment in the early seventeenth century. Ana Nzinga, queen of the Ndongo (c. 1581–1663) was an equally formidable opponent, a fearsome woman who remained a flea in the ear of the Portuguese throughout her thirty-year reign. As well as keeping a harem of both male and female consorts, she is said to have dressed in men’s clothing and insisted on being called ‘king’ rather than ‘queen’.

Her brazen, imperious character is legendary. During her first encounter with colonial governor Correia de Sousa, she is said to have refused his offer of a seat on the floor, ordering one of her servants to get down on his hands and knees instead to form a chair. Later, under the pretence of forming an alliance with them, she allowed herself to be baptised Dona Ana de Souza and learnt the Portuguese language. Distrusted by the Portuguese for her habit of harbouring escapees and much feared for her military prowess when resisting European intrusion, she point-blank refused to become their puppet and was never effectively subdued.2

Even though resistance to European traders was sporadic and mercilessly repressed, it persisted in some form or another for centuries. Their names may have been lost to us, yet women are known to have played a significant role militarily, spiritually and politically. Several historical accounts confirm the influence of African women as leaders and warriors: Amina or Aminata (d. 1610), the warrior Hausa queen of Zazzau (modern-day Zaria), led an army of over 20,000 in her wars of expansion and surrounded her city with defensive walls that are known to this day as ganuwar amina or ‘Amina’s walls’. Described in Hausa praise songs as ‘a woman as capable as a man’, she reigned for over thirty-five years.3

There was also Beatriz Kimpa Vita (1684–1706) of the Congo, who insisted that Jesus was an African and whose call to Congolese unity was taken as a direct challenge to the designs of European slavers and missionaries. Burnt at the stake as a heretic together with her infant son, her spiritual influence spread so far and wide that enslaved Haitians used the words from one of her prayers as a rallying cry when they rose in rebellion almost a century later.4

Over 200 years after Ana Nzinga’s rule, warrior queen Yaa Asantewaa came to embody this spirit of female resistance when, as the chosen leader of the Ashanti in their struggle against British colonialism, she denounced her fellow chiefs for allowing their king, the Asantehene, to be seized and exiled. In her words:

Now I have seen that some of you fear to go forward to fight for our king. If it were the brave days of Osei Tutu, Okomfo Anokye and Opuku Ware I, chiefs would not sit down to see their king taken without firing a shot. No white man could have dared to speak to the Chief of Asante in the way the governor spoke to you chiefs this morning. Is it true that the bravery of Asante is no more? I cannot believe it, it cannot be! I must say this: if you, the men of Asante, will not go forward, then we will. I shall call upon my fellow women. We will fight the white men. We will fight till the last of us falls on the battlefield.5

Yaa Asantewaa, born in 1840, would have been around sixty when she was elected to lead an army of 5,000 in the Ashanti war of resistance against the British at the turn of the twentieth century. Described by the British as ‘the soul and head of the whole rebellion’, she is thought to have been the mother or aunt of a chief who had been sent into exile with the king. Although she was eventually defeated and exiled herself, she remains a Ghanaian national she-ro and a figure of inspiration to this day for her refusal to bow down to colonial rule.

This is not to suggest that recalcitrant men didn’t play an equally important role in resisting the theft of their people. In 1720, Tomba, chief of the Baga, attempted to organise an alliance of popular resistance that would drive the traders and their agents into the sea. The Oba (kings) of Benin are also reputed to have been opposed to the trade for many years.6 King Agaja II of Dahomey, whose reign lasted from 1718 to 1740, is said to have been so incensed by the incursion of traders into his kingdom that he raised an army of intrepid women to help resist them. A letter, thought to have been dictated and sent by Agaja to the English king, George II, in 1731, even went so far as to propose an alternative scheme of trade, substituting the export of human beings with exports of home-grown sugar, cotton and indigo.7

On second thought, King Agaja may not be the best example of male agency. His palace was ‘a virtual city of women, experienced in the mechanics of government’ – close to 8,000 women, whose roles included blocking or promoting outsiders’ interests. Said to have exercised choice, influence and autonomy, they wielded considerable authority and power. This ferocious army of Amazonian ‘soldieresses’ was legendary both for the warriors’ physical prowess and their elevated status. They called themselves N’nonmiton (‘our mothers’) and others saw them as elite, aloof and untouchable.

As bodyguards to the king, they were trained to display speed, courage and physical endurance on the battlefield, and expected to fight to the death to protect him. Their fearsome, ruthless legacy is remembered to this day.8

There were other kings who resisted, too. According to Carl Bernard Wadstrom, who made a voyage to the coast of Guinea in 1787, the King of Almammy was so opposed to the trade that he enacted a law forbidding the transport of slaves through his territory. Wadstrom was an eyewitness when the king returned gifts sent by the Senegal Company in an attempt to win him over, declaring that ‘all the riches of that company would not divert him from his design’. Even toward the end of the eighteenth century, by which time the trade was well entrenched, the inhabitants of the Grain Coast were known both for their reluctance to trade in slaves and their habit of attacking European slavers who attempted it.

Sadly, back in Europe, such protests fell on deaf ears. After all, why concern themselves with the plight of Africans when there were such huge profits to be made? Aside from copious supplies of rum and gin, which created their own dependency, one of the most lucrative exports to Africa at the time was guns. Between August 1713 and May 1715, the Royal African Company ordered no less than 11,986 fusees, pistols, muskets and Jamaica guns for export to the Guinea coast,9 the latter made specifically for the slave trade and known for their habit of exploding the first time they were fired.10 King Tegbesu of Dahomey (King Agaja’s successor) is said to have complained bitterly that a consignment of English guns had exploded when used, injuring many of his soldiers. In 1765, a fairly typical year, 150,000 guns were exported to Africa from Birmingham alone – the beginnings of an ignominious arms trade that has killed or maimed millions of Africans and has continued unchecked into the twenty-first century.

Before long, power and guns would become inextricably linked, with the price of a slave costing anything from one to five guns, depending on the location of the sale. Soon captive Africans, typically prisoners of war, had replaced gold, ivory, pepper and redwood as the primary currency. Meanwhile, resident European factors, whose ‘palavers’ with less scrupulous local rulers left them well placed to stir up local rivalries, were often charged with deliberately fomenting unrest in a cynical move to increase demand for guns and the resulting supply of captives.

The truth is although it was Europeans who organised the triangular trade in their scramble for profit and influence, they could not have done so without co-opting some extremely power-hungry Africans. The collusion of chiefs and indigenous traders was the inevitable by-product of a system that thrived on avarice. Elmina, like hundreds of other forts and trading posts along the West African coast, would soon become a busy commercial hub, its predominantly European occupants dependent on local communities for water, fresh food, transport and, in some cases, even armed protection.

Bogus treaties with local chiefs may have given Europe’s traders an initial foot in the door, but their success – and, on some occasions, their very survival – came to rely on the services of local people: boatmen, domestic servants, messengers, traders, brokers, interpreters and so-called ‘wenches’. For them and their descendants, this trade in fellow humans would ultimately become a way of life. Treacherous currents and diseases that could devastate an entire crew encouraged European ships to anchor far offshore for their own safety. The trade would have died an early death but for the expertise of local boatmen, who were handsomely rewarded for ferrying people and goods to and from the waiting ships. If they were fortunate enough to escape capture themselves, it was only because their skills in handling the canoes, sometimes as long as eighty feet and able to carry over 100 people, were vital to the endless traffic between ship and shore.

Within 200 years, what began as a Portuguese monopoly in 1490 had become a free-for-all. As the British, French, Danish, Dutch, Prussians, Spanish and Swedish jostled with the Portuguese for strategic dominance of the coastal forts and supply routes, competition was fierce, often deadly. Elmina Castle, seized by the Dutch in 1642, changed hands several times until finally, over two centuries lat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Map

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: His-story, Her-story

- 1. A Terrible Crying: Women and the Africa Trade

- 2. A World of Bad Spirits: Surviving the Middle Passage

- 3. Labour Pains: Enslaved Women and Production

- 4. Equal under the Whip: Punishment and Coercion

- 5. Enslaved Women and Subversion: The Violence of Turbulent Women

- 6. Choice or Circumstance? Enslaved Women and Reproduction

- 7. The Carriers of Roots: Women and Culture

- Afterword

- Notes

- Index