eBook - ePub

Ancient Perspectives

Maps and Their Place in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Perspectives

Maps and Their Place in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome

About this book

Ancient Perspectives encompasses a vast arc of space and time—Western Asia to North Africa and Europe from the third millennium BCE to the fifth century CE—to explore mapmaking and worldviews in the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. In each society, maps served as critical economic, political, and personal tools, but there was little consistency in how and why they were made. Much like today, maps in antiquity meant very different things to different people.

Ancient Perspectives presents an ambitious, fresh overview of cartography and its uses. The seven chapters range from broad-based analyses of mapping in Mesopotamia and Egypt to a close focus on Ptolemy's ideas for drawing a world map based on the theories of his Greek predecessors at Alexandria. The remarkable accuracy of Mesopotamian city-plans is revealed, as is the creation of maps by Romans to support the proud claim that their emperor's rule was global in its reach. By probing the instruments and techniques of both Greek and Roman surveyors, one chapter seeks to uncover how their extraordinary planning of roads, aqueducts, and tunnels was achieved.

Even though none of these civilizations devised the means to measure time or distance with precision, they still conceptualized their surroundings, natural and man-made, near and far, and felt the urge to record them by inventive means that this absorbing volume reinterprets and compares.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ONE

The Expression of Terrestrial and Celestial Order in Ancient Mesopotamia

Francesca Rochberg

I. Introduction

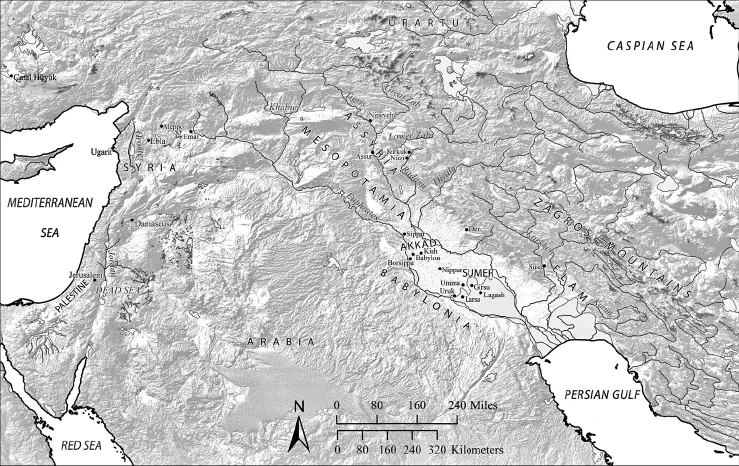

The earliest examples of historical maps are traceable to the ancient Near East (fig. 1.1), where first Sumerians and Akkadians, and later Babylonians and Assyrians, developed the landscape of Mesopotamia by building houses, temples, palaces, cities, and states. Sumerian and Babylonian iconographic representation of features of the land and the built environment is known for the entire history of the cuneiform writing tradition, from the early third millennium to nearly the beginning of our era in Late Babylonian texts. Because of the diversity of the source material, mapmaking in ancient Mesopotamia has not been studied as a thematically unified corpus. The aim here is to afford a general overview and to make some comments on the various Mesopotamian cultural contexts for mapmaking. Completeness has not been a primary objective. Because of the sheer number of examples it is not possible to discuss each and every map on cuneiform tablets.1 The following overview will move from the large (or local) scale to the small (or global) scale, beginning with evidence for plans of houses and other buildings, then proceeding to field surveys, city maps, regional maps, a map of the world, and finally the establishment of a spatial organization in the heavenly cosmos. The discussion will therefore not be strictly chronological, but each section will proceed from earlier to later examples.

Even in the prehistory of the Near East, a “map” from the Neolithic site Çatal Hüyük in central Anatolia attests to social awareness of the inhabited place and its relation to its geographic surrounds. Found in 1963 by the archaeologist James Mellaart during the excavation of Çatal Hüyük near Ankara, Turkey, this 3 m red-brown polychrome wall painting, radio carbon dated to approximately 6200,2 appears to represent the town itself with eighty rectangular buildings of varying sizes clustered in a terraced town landscape (fig. 1.2 and plates 1a and 1b). Mellaart noted the similarity of the representation of the houses to the actual excavated structures found at the site, that is, rows of houses built one beside the other with no space between them. The wall painting shows an active double-peaked volcano rising over the town, likely to be the 3,200 m stratovolcano Mount Hasan, which is visible from Çatal Hüyük. Lava is depicted flowing down its slopes and exploding in the air above the town. A cloud of ash and smoke completes the scene.3

FIGURE 1.1 Map of the Ancient Near East. Adaptation by the Ancient World Mapping Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, of J. B. Harley and David Woodward, eds., The History of Cartography, vol. 1, Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 108, fig. 6.1.

While not a map in the sense of a surveyed and measured image of some part of the earth’s surface, the image of the town with its local mountain spewing molten rock is a representation of a phenomenon that one can well imagine was actually experienced. In the context of other prehistoric European maps, Catherine Delano-Smith (1982) speculated that the representation of this geographic scene most likely had a ritual function. The map was not meant as a projection of a landscape upon a measured framework or even as a lasting representation, as the walls of the dwellings at Çatal Hüyük were regularly replastered and painted over. As Delano-Smith put it (1982, 18), “If villages and fields were depicted in it, they would have been associated less with the ‘objective’ recording of a spatial distribution for purposes of direction or reference than with invoking the favours of the controlling forces of those aspects of life these topographical features were used to represent or with attempts to appease them.” Of course, such interpretations are conjectural in the absence of contemporary written evidence. As will be clear in this presentation, however, even in the presence of contemporary written evidence, the nature and motivations of mapmaking in the ancient Near East are not always easy to assess. The Çatal Hüyük map, while certainly not a map in the familiar sense, shares aspects with other ancient Near Eastern maps which reflect a desire to represent, for whatever reason, real aspects of the visible terrain of the immediate environment.

FIGURE 1.2 Part of a representation of a town in a Neolithic wall painting from Çatal Hüyük, Turkey, dated to the early seventh millennium BCE. Approximately 3 m in length. Image reproduced from J. Mellaart, “Excavations at Çatal Hüyük, 1963, Third Preliminary Report,” Anatolian Studies 14 (1964): 55 and pl. V. Photograph by James Mellaart, reproduced with permission.

One of the functions of ancient Near Eastern maps is the representation of architectural or topographical order imposed on the physical landscape, or the idea of the physical landscape, both terrestrial and celestial. Mesopotamian maps do not guide the traveler from one place to another, but rather represent those ordered features imposed by human beings on the natural world, either physically, such as the temple, the city, agricultural lands, roads, and canals, or philosophically, as in notions of a world inclusive of known and unknown regions shown in diagrammatic form on the one surviving Babylonian world map. They are maps in the sense that a map is, as defined by Denis Wood (1992, 122), “an icon, a visual analogue of a geographic landscape . . . the product of a number of deliberate, repetitive, symbolic gestures . . . formal items—the discrete elements of iconic coding . . . shaped within the space of the map . . . or preformed and imposed on the map, activating formal symbolism and formal metaphor as well.”

This definition of the map as an icon, and mapmaking as a process of developing iconic codes for representing topographical features, is useful for pulling together disparate sets of evidence that can be viewed together within a coherent framework of “mapmaking” in the ancient Near East. The features of the topography that eventually warranted representation, such as houses, temples, agricultural fields, and cities, distinguish undeveloped land from property. Mesopotamian maps were not exercises in the objective rendering of geography or the unbuilt landscape. One might say that land was not mapped; rather, property was. The reasons that made different kinds of property worthy of being mapped varied from economic to religious and cosmic.

Practical geography, on the other hand, is represented in literary form, in itineraries attested from Old Babylonian times up to Neo-Assyrian, that is, from the eighteenth to the seventh centuries. Their interpretation and their use for reconstructing ancient landscapes is fraught with difficulty, because the identification of toponyms and their relative distances from one another is often uncertain.4 The itineraries do often provide distances, given in months and days, or, in the case of the later examples, in the unit of distance and time called bēru (danna), which we translate as the “double-hour,”5 and which was also adopted for use in measuring stellar and other celestial distances in astronomical texts. Indeed, the bēru was the pervasive measure of both distance and time in celestial terms, as it was a one-twelfth subdivision of the nearly constant unit of the day (ud), the interval between successive sunsets. The celestial “double-hours” stem from the correlation made between the length measure of twelve terrestrial bēru and the fixed time measure of one day (ud). In view of the term’s Sumerian etymology—KASKAL.GÍD = danna, “long road”—the original length measure of the bēru referred to the distance traversable on foot in the time it would take for the sun to travel thirty degrees across the sky, or one-sixth the length of daylight (assuming an equinoctial day of twelve daylight hours). The distance of one bēru would then correspond roughly to a two hours’ march. Such a correlation between terrestrial distances and the division into twelfths of the “day,” or rotation of the sky, is, in a concrete sense, geodetic.

Not only on earth but in heaven too, structural order was imposed by the transposition and projection of terrestrial features of the built and cultivated environments from earth to heaven. The horizon was the “cattle pen,”6 and the heavenly bodies the cattle and sheep that followed their orderly, or, in the case of planets, somewhat less orderly, paths (Rochberg 2010). The religious text Enūma Eliš, also known as the Babylonian Creation Epic, uses this double metaphor for the gods as both celestial bodies and livestock when it says, “Let him (the creator god Marduk) assign the regular motions of the stars of heaven; let him herd all the gods like sheep” (Enūma Eliš VII 131). In addition, the regular paths followed by the stars across the sky from their risings to their settings were compared to furrows of a field.7 The fixed stars were also attached to specifically named “roads” serving to mark their directions, and the moon too moved against the starry background along what was called “The road of the moon” (harrān dSin).

Other units familiar from the texts of land surveyors, the cubit or “forearm” and finger, are also found in astronomical contexts where distance between celestial bodies is in question. Despite a dearth of iconographic representation of the celestial roads and the arrangement of constellations within them, there survives noniconographic textual evidence making reference to double-hours, cubits, and fingers (bēru, ammatu, and ubānu, respectively) within the heavenly roads or with respect to other devices for fixing celestial positions, such as the ecliptical stars. These references show that such imagery and its associated metrology had currency throughout the cuneiform tradition of astral sciences. Celestial mapmaking, as we would recognize it, is not well represented, despite the application of units of time-distance such as bērus and degrees to the measurement of relative positions of celestial objects. Although the surviving iconographic evidence for “mapping” the heavens is extremely limited (see III.2 below), a practical astronomy that systematically organized, schematized, and predicted celestial phenomena shows that the celestial landscape was quite well “mapped,” in fact.

Extant cuneiform maps cannot be considered to constitute a coherent tradition of cartography in which a continuous evolution of mapping techniques or even conceptions of the map itself are evident over time. Nonetheless, various aspects of the ancient Mesopotamian physical world, both terrestrial and celestial, are represented on cuneiform tablets over a considerable time span. These representations are eminently classifiable as cartographic, even according to the definition of professional cartography by the British Cartographic Society as “the science and technology of analyzing and interpreting geographic relationships, and communicating the results by means of maps” (Harley 2001, 151).

Mesopotamian maps have not always been readily incorporated into the history of cartography. In older scholarship resistance to including them can be found even with regard to the best-known example, the so-called Babylonian mappamundi from the later eighth or early seventh century. In his introduction to the 1959 reissue of Edward Bunbury’s 1883 History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans from the Earliest Ages till the Fall of the Roman Empire, William Stahl characterized this map as a crude representation (p. iii): “Before the time of the ancient Greeks, geography and cartography were in a primitive state. The early Babylonians, for example, had developed remarkable precision and skill in observing and predicting the orderly movements of celestial bodies, but their conceptions of the earth were what one might expect of a relatively isolated people. A Babylonian clay tablet . . . depicts the earth as a circular plane, bisected by the Euphrates River, with the capital city of Babylon located near the center and a few adjacent countries bordering upon an encircling ocean.” Stahl’s condescension takes it for granted that the map was intended as a direct and accurate rendering of its subject, and that its maker was a scientist with goals of precision and accuracy. However, such a position assumes criteria for mapmaking that will not be met by most ancient Near Eastern exemplars.

Recent cartographic historiography has revised the concept of what a map is (or what it is to make a map) and has consequently opened the way to consideration of maps as representations not only of the environment as a physical object, but also of notions of the environment, imagined, abstracted, or ideal realms of the world beyond the concrete features of the immediate experienced terrain (MacEachren 1995, 255–56). In particular, Brian Harley has articulated again and again the value of reassessing the history of maps and redefining cartography in accordance with evidence of its practice...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. The Expression of Terrestrial and Celestial Order in Ancient Mesopotamia

- 2. From Topography to Cosmos: Ancient Egypt’s Multiple Maps

- 3. Mapping the World: Greek Initiatives from Homer to Eratosthenes

- 4. Ptolemy’s Geography: Mapmaking and the Scientific Enterprise

- 5. Greek and Roman Surveying and Surveying Instruments

- 6. Urbs Roma to Orbis Romanus: Roman Mapping on the Grand Scale

- 7. Putting the World in Order: Mapping in Roman Texts

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index

- Plate Section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ancient Perspectives by Richard J. A. Talbert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.