- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Located in the heart of England's Lake District, the placid waters of Thirlmere seem to be the embodiment of pastoral beauty. But under their calm surface lurks the legacy of a nineteenth-century conflict that pitted industrial progress against natural conservation—and helped launch the environmental movement as we know it. Purchased by the city of Manchester in the 1870s, Thirlmere was dammed and converted into a reservoir, its water piped one hundred miles south to the burgeoning industrial city and its workforce. This feat of civil engineering—and of natural resource diversion—inspired one of the first environmental struggles of modern times. The Dawn of Green re-creates the battle for Thirlmere and the clashes between conservationists who wished to preserve the lake and developers eager to supply the needs of a growing urban population. Bringing to vivid life the colorful and strong-minded characters who populated both sides of the debate, noted historian Harriet Ritvo revisits notions of the natural promulgated by romantic poets, recreationists, resource managers, and industrial developers to establish Thirlmere as the template for subsequent—and continuing—environmental struggles.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dawn of Green by Harriet Ritvo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2009Print ISBN

9780226720869, 9780226720821eBook ISBN

97802267208451

The Unspoiled Lake

In 1875 local residents began to sense that property around Thirlmere was attracting unusual attention. First there was unobtrusive surveillance, then cryptic purchases of land. The members of the Manchester Waterworks Committee, who had identified the long narrow lake as a likely site for the city’s urgently needed new reservoir, hoped that low-key tactics would discourage suspicion and keep asking prices low. Those hopes were doomed to disappointment. The deliberations that had led them to Thirlmere were not completely secret, and simple prudence required that they examine the potential site of such a significant investment before committing to it. It was difficult to keep such hands-on explorations inconspicuous.

One expedition began tamely enough at Ullswater, a neighboring lake that was also initially under consideration. Having finished its business there by early afternoon, the surveying party decided to walk to Thirlmere over Helvellyn, one of the highest of the Lake District hills. This route proved more challenging than anticipated. The two oldest members of the group, one of whom “could not walk very well” even in ordinary circumstances, eventually began to flag and had to take turns riding the single pack horse, which meant that their fitter companions had to hike with the baggage. At one point, the horse sank to its knees in a peat bog, from which it was extricated only with difficulty, and two of the walkers injured themselves seriously descending a hillside in the dark. They did not reach Thirlmere until ten at night, when they abandoned themselves to the mercies of a local public house. There they waited several hours longer for a carriage to take them to their hotel in Keswick, more than ten miles away.1

On another occasion two dignified members of the Waterworks Committee wished to observe the lakeshore from the grounds of the leading local landowner, who had explicitly denied them access and “threatened severe measures if he found any of them ever hanging about his property.” They therefore approached the forbidden vantage point by way of the fields, rather than from the road, creeping past the manor house on hands and knees, concealed in soaking vegetation. After completing their reconnaissance, they had to endure the long ride back to Keswick in wet clothes; both became ill and “were laid up for some days.”2 Merely alarming was the experience of one of their colleagues, who ventured onto Helvellyn for an aerial view of Thirlmere one sunny winter afternoon, after completing a purchase of land near the lake, and found himself climbing down through “blinding snow.”3

In their choice of Thirlmere as the prospective site of a reservoir, and in their first tentative ventures into the Lake District, the members of the Manchester City Council were guided by Alderman John Grave. Born in Cockermouth, where his father was a saddler, he made his fortune manufacturing cotton and paper in Manchester.4 He had maintained his connection with his native Cumberland and owned a house near Keswick, from which base he would later be accused of “carefully nursing the whole district . . . , buying here and there.”5 But before any buying could be done, it was necessary to learn more about individual holdings, whether large estates or modest farms, than could be gleaned by mere visual inspection. Once his fellow Cumbrians got wind of Grave’s plan, however, neither his local roots nor his “very speculative turn of mind” would help him to elicit sufficient (or sufficiently accurate) information.6 Any identifiable representative of the Manchester Corporation would be stonewalled by canny property owners mindful of future negotiations. So three local ringers received discreet appointments as “special commissioners.” All pursued occupations that provided natural cover for peripatetic inquiry: one was a cattle dealer, one a building contractor, and the third (best of all) was Henry Irwin Jenkinson, a champion fell walker and the eponymous author of Jenkinson’s Practical Guide to the English Lake District.7 Since, at least according to an uncharitable retrospective view, his research subjects hoped that he would bring “the innocent and unsuspecting tourist into the locality, for the purpose of being skilfully fleeced, information was freely and readily imparted.”8

As it turned out, however, financial concerns were not uppermost in the minds of most local landowners when they became aware of Manchester’s interest in Thirlmere. And reticent though they might have been about the details of their property, they were more than forthcoming with their opinions of the prospective appropriation. It pleased them not at all. The determined opposition of Thomas Leathes Stanger Leathes, whose property included not only Dalehead Hall, the most imposing home on the lakeshore, but also the lake itself, turned out to be a straw in the wind. Less prominent residents, already nerved to resist a rumored extension of the Lake District railway service into their neighborhood, shared his reluctance to see Thirlmere and its surrounding valley transformed to meet remote urban needs.9 Proclaiming their allegiance to a landscape conceived both romantically and traditionally, they organized to oppose the forces of progress and materialism, industry and economics, of which Manchester was both the representative and the symbol. The Manchester City Council members and their agents were surprised by the energy of this resistance and by its far-reaching appeal. Their Cumbrian antagonists quickly began to receive moral and material support from throughout the nation, and indeed the Anglophone world. A confrontation that the projectors had expected to play out in familiar commercial terms slipped uncontrollably into the realm of ideology and myth, since if Manchester was the icon of the Victorian future, the Lake District was the icon of nature, poetry, and heritage.

The Lake Itself

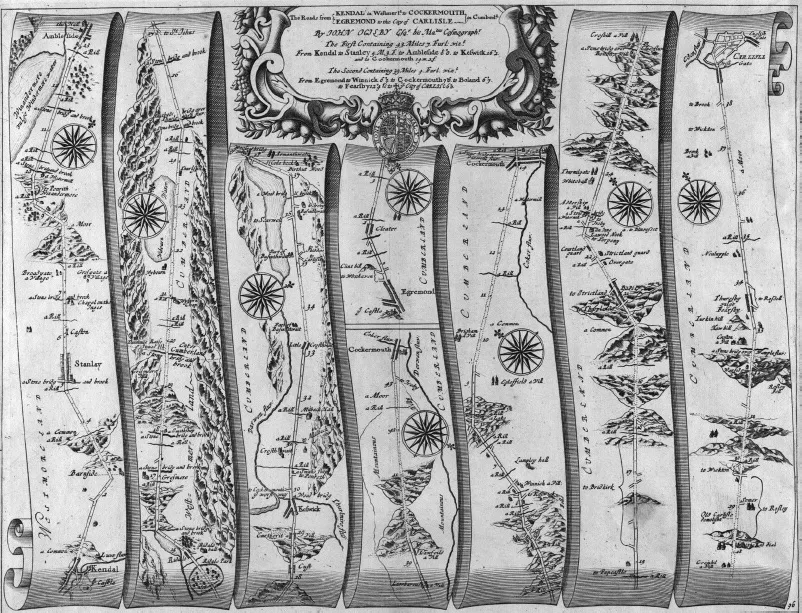

Before its emergence as the object of Mancunian desire, Thirlmere had played a relatively modest part in the history of Lake District appreciation. This history stretched back for nearly two centuries. Tourists had begun to visit the remote hills of Cumberland and Westmorland at the end of the seventeenth century, although at first not all were pleased with what they encountered. Daniel Defoe, for example, found the Cumbrian landscape “eminent only for being the wildest, most barren and frightful of any that I have passed over in England, or even in Wales itself.”10 By the middle of the eighteenth century, however, aided by the accounts of more responsive viewers like the poet Thomas Gray, travelers were learning to love the dramatic valleys and rugged hilltops.11 In addition, the Lake District had become somewhat more accessible as a result of the construction of new roads. Particularly effective in opening up the heart of the area was a turnpike trust established in 1761 to improve the highway between Kendal and Keswick, the most important towns.12 The northwestern portion of this road, which ran from Windermere (by far the largest of the lakes) to Keswick, was later said to be “the trunk of the District . . . it traverses through twenty-one miles of, perhaps, the most beautiful highway-scenery in England.”13

Thirlmere, labeled “Wiburn Water,” seemed very remote in the seventeenth century.

By the time that George Culley and John Bailey made their agricultural survey of the lake counties at the beginning of the nineteenth century, they parenthetically noted that the area was “ornamented with many beautiful and extensive lakes; which, with their pleasing accompaniments have of late years made the tour of the lakes a fashionable amusement.”14 Along with tourists came the infrastructure of tourism: inns, carriages, guides, and guidebooks.15 Aficionados of the picturesque had even begun to build houses so that they could appreciate the scenery on a more protracted basis.16 As aesthetic sensibilities grew less restrained, the charms of Cumbria became still more compelling. It was because “the scenery of Westmoreland and Cumberland cannot be exceeded in varied grandeur and beauty” that a travel book published in 1821 could claim that “England . . . can vie with any country in Europe in wild and romantic scenery” and, still more strongly, that “in all that constitutes the perfection of romantic landscape, England is without a rival.”17 That is, as a slightly earlier traveler had put it, “Nature” could be judiciously admired in the Lake District without “the eye . . . being either glutted by expanse, or DISGUSTED by deformity,” hazards that awaited the sensitive English tourist in Switzerland and other foreign destinations.18 Looking back in 1867, the anonymous reviewer of ten books about the Lake District commented, “It is most curious to contrast the descriptive language with which we are familiar, with the descriptions, expressive rather of repugnance than of admiration, which belong to an earlier time.”19

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, the physical attractions of the Lake District were enhanced by literary association.20 William Wordsworth, Robert Southey, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who became known as the Lake poets, made the area both their subject and, for varying periods, their home. Wordsworth, like John Grave a native of Cockermouth, had spent most of his schooldays in the isolated vale of Esthwaite, and he returned to the neighborhood of Grasmere, more conveniently situated near the main road, for most of his long adult life.21 His poetic evocations of the striking Cumbrian landscape and his passionate response to it inspired many readers to make their own pilgrimages. Their advent not only boosted the nascent hospitality industry, but generally enhanced the prosperity of local landowners. As one of them testified much later, during the contention over Manchester’s reservoir plans, “Wordsworth has done . . . more than any land improver can do; he has doubled and trebled the value of the property by the associations.”22

Wordsworth was to remain ambivalent about Lake District tourism and his own role in promoting it. At some times he encouraged it through his writing, while at others he lamented the predictable consequences and even attempted to undo them. He countered the most excitable strain of touristic response implicitly, by example. In 1810 he anonymously published the first version of a guidebook (he took credit for subsequent editions) that offered rather down-to-earth descriptions of the local attractions. He credited his ideal audience, which he imagined to consist of “Persons of taste, and feeling for Landscape, who might be inclined to explore the District of the Lakes with that degree of attention to which its beauty may fairly lay claim,” with similarly judicious restraint.23 But it was difficult to suppress altogether the more extravagant responses of such readers as the essayist Thomas De Quincey, who like many others, was drawn to Cumberland and Westmorland by Wordsworth’s poetry. (De Quincey, again like many others, was also drawn to the man himself; by the end of his life, both Wordsworth’s house and his person figured routinely in tourist itineraries, along with the settings of his best known poems.) In his enthusiastic reconstruction of Wordsworth’s childhood experiences, De Quincey characterized the Lake District as a “domestic Calabria” (probably a mixed compliment, at least with regard to its human population), a “paradise of virgin beauty, . . . even the rare works of man . . . were hoar with the gray tints of an antique picturesque.”24

Whether attracted to Cumbria’s scenery or to its literary refraction, almost all visitors included Thirlmere in their itineraries. Indeed, it was difficult for them to avoid at least glimpsing it, because the carriage road from Kendal and Windermere to Keswick ran along the eastern shore of the lake, shadowed by the massive bulk of Helvellyn. Because Thirlmere lay in a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The Unspoiled Lake

- Chapter 2. The Dynamic City

- Chapter 3. The Struggle for Possession

- Chapter 4. The Cup and the Lip

- Chapter 5. The Harvest of Thirlmere

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Illustration Credits

- Index