- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Drive the streets of Nairobi, and you are sure to see many matatus—colorful minibuses that transport huge numbers of people around the city. Once ramshackle affairs held together with duct tape and wire, matatus today are name-brand vehicles maxed out with aftermarket detailing. They can be stately black or extravagantly colored, sporting names, slogans, or entire tableaus, with airbrushed portraits of everyone from Kanye West to Barack Obama. In this richly interdisciplinary book, Kenda Mutongi explores the history of the matatu from the 1960s to the present.

As Mutongi shows, matatus offer a window onto the socioeconomic and political conditions of late-twentieth-century Africa. In their diversity of idiosyncratic designs, they reflect multiple and divergent aspects of Kenyan life—including, for example, rapid urbanization, organized crime, entrepreneurship, social insecurity, the transition to democracy, and popular culture—at once embodying Kenya's staggering social problems as well as the bright promises of its future. Offering a shining model of interdisciplinary analysis, Mutongi mixes historical, ethnographic, literary, linguistic, and economic approaches to tell the story of the matatu and explore the entrepreneurial aesthetics of the postcolonial world.

As Mutongi shows, matatus offer a window onto the socioeconomic and political conditions of late-twentieth-century Africa. In their diversity of idiosyncratic designs, they reflect multiple and divergent aspects of Kenyan life—including, for example, rapid urbanization, organized crime, entrepreneurship, social insecurity, the transition to democracy, and popular culture—at once embodying Kenya's staggering social problems as well as the bright promises of its future. Offering a shining model of interdisciplinary analysis, Mutongi mixes historical, ethnographic, literary, linguistic, and economic approaches to tell the story of the matatu and explore the entrepreneurial aesthetics of the postcolonial world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Matatu by Kenda Mutongi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2017Print ISBN

9780226471396, 9780226130866eBook ISBN

9780226471426Part One

Background

Introduction

Matatu

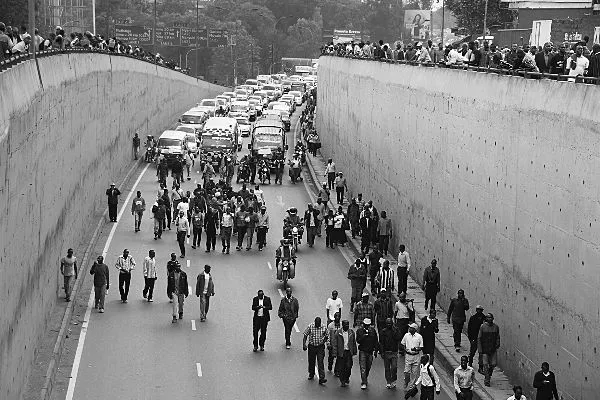

Without its matatus, the city of Nairobi comes to a near standstill.1 It happens some ten to fifteen times a year when matatu workers go on strike. Whenever they suspend their scramble through the streets, everything in the city slows down—the town center grows quiet, offices sit empty, stores close their doors, and the last lingering pedestrians are able to walk the sidewalks with ease. There are no commuter trains or trams, the traffic and poor road conditions make cycling impossible, and the government, regrettably, provides only a few irregular and ineffective buses. Since so few people can afford private cars, a majority of people have come to rely upon matatus, the privately owned minibuses that have engulfed the city over the past half a century. Unfortunately, the citizens of Nairobi have become used to the matatu strikes, used to waiting on dusty side roads and crowded street corners until, angry and out of patience, they abandon hope and either trudge home or hike into town. Whenever the city’s moving mosaic of matatus comes to a stop, the forsaken commuters are once again reminded of just how much their lives depend on these flamboyant minibuses and the army of workers who operate them. Inevitably, the offices, cafés, and dukas begin to echo with resentment, and the muttered complaints of the stranded rise like bitter clouds of exhaust—“tumeshindwa kabisa!”

In other words, without the matatus Nairobi’s commuters feel “completely defeated.” The familiar phrase expresses more than simple frustration at the lack of transportation. It also reveals a sense of thwarted prospects, even a sense of national failure, at least to the extent to which the whole of the city and its economy have come to depend on these vehicles. To the uninitiated outsider, this sense of gloom can be baffling. Those unfamiliar with the city’s culture tend to see matatus as little more than a noisy, garish way for residents to get about the city; at worst, they look at the encroaching chaos of matatus as if it were nothing better than a gang of venal marauders—strident, greedy, relentless—intent upon vanquishing the city with their custom-built coaches. But despite the ambivalence with which the matatus are viewed, the citizens of Nairobi have come to acknowledge, reluctantly, that they are instrumental to the city’s success. It is unlikely that Nairobi’s economy could survive without the overwhelming achievements of the matatu industry. Since the early 1960s, the matatu has provided transportation to at least 60 percent of the city’s population, and the matatu industry has become the largest employer in the so-called popular economy by providing livelihoods to mechanics, touts, fee collectors, drivers, artists, and other associated businesses.2 Even more significant is the fact that the matatu industry is the only major business in Kenya that has continued to be almost entirely locally owned and controlled; in other words, it has, from its beginnings, remained free from the influence of foreign aid or foreign aid workers.3 The matatu industry is homegrown. The owners and workers are making it on their own, without foreign aid or government support, and despite subsidized competition, government interference, and systemic corruption. For several decades now, the matatu industry has provided a rare example of a highly profitable business that has turned out to be vital to the development of Nairobi and its identity—as the acclaimed Kenyan writer and activist Binyavanga Wainaina has remarked, “Matatus are Nairobi and Nairobi is matatus.”4

Figure 1 Matatu workers’ strike, May 9, 2012. Courtesy of the NMG, Nairobi

In fact, matatus are so much a part of life in the city that it is no exaggeration to say that modern Nairobi could not have taken shape without the invention of these colorful contraptions. The two cannot be separated. They are too mutually dependent, too tightly intertwined. Not only is the motley stampede of transports inescapable to anyone on the street, but they have also, since independence, existed at the heart of the city’s economy and its culture, politics, and street life. They have, over the past half century, provided the city with its circulatory system; they are its lifeblood. So, to understand the history of Nairobi and its rapid growth, we need to understand the history of the matatu; similarly, if we want to understand the triumph of the matatu, we need to understand the particular social, economic, cultural, and political history of postcolonial Nairobi.

This uneasy alliance of Nairobi and its matatus is the subject of this book. It is the story of the matatu industry as it unfolds within the larger historical contexts of the community and the nation, from its beginnings in the early 1960s through the authoritarian years of Daniel Arap Moi’s presidency, and into the twenty-first century.5 Given the industry’s humble origins, as well as its ad hoc, opportunistic nature, the book is necessarily an ethnographic history, written from the perspective of the streets. The story of the matatu cannot be found anywhere else, anywhere but on the peripheries of society, on the rough streets and in dirty garages, and among the grease-stained entrepreneurs who tend to thrive outside the purview of bureaucrats and politicians—and all too often outside the law. And though the story may start around the margins of Nairobi, it does not end there. Eventually the history of the matatu will take everyone involved—the workers, the passengers, the police, the gangs, and the government—on a rough ride straight into the center of the city.

Matatu-like transportation is not unique to Kenya. The use of vehicles similar to matatus is an important phenomenon in most of the Global South. Called pesero in Mexico, jeepney in the Philippines, tuk-tuk in Indonesia, songthaew in Thailand and Laos, otobus in Egypt, combi in South Africa, dala dala in Tanzania, danfo in Nigeria, taxis-brousses in Francophone Africa, they can be found throughout areas with uneven development, popular economies, and a large-scale need for public transportation. In Nairobi it became relatively commonplace to see a matatu on the roads right after Kenya achieved its independence from Britain. They could not have existed earlier. During colonial rule, Nairobi was meant to be a white-only city, and the idea of an African-owned vehicle bringing Africans into the city was not encouraged. Not only were major African business ventures generally discouraged, the movements of Africans were also vigilantly restricted.6 Typically, the only Africans allowed to remain in the city center for more than brief visits were laborers performing menial work for Europeans, and most of these workers walked to their places of work. They had no choice. This changed significantly once racial restrictions were lifted after independence in 1963 and Africans could work and move about the city more freely. The effects of freedom were immediate, throughout the country. Straightaway Africans began migrating from the rural areas to the city in search of economic opportunity and excitement, and the majority of these new residents needed a way to get around the city and to get into the city from the rapidly growing suburbs. And so the matatu was invented.

The early matatus were ramshackle affairs (the name “matatu” derives from the Kikuyu word for “three,” the three big ten-cent coins used to pay for a ride to the city). They were cobbled together “bit by bit, piece by piece,” recalled one Nairobi resident who witnessed the birth of matatus in the early 1960s: “Matatu entrepreneurs scrounged old motor parts and carried them to garages on River Road. After weeks of hammering and tying pieces of wire, an earsplitting roar, accompanied by machine-gun-type backfiring, was heard, [then] huge mechanical monsters emerged from behind. After a long time, the engine fired and broke into a tremendous roar, and the turn-boys removed the stones that kept the wheels in place.”7 For the most part these enterprising businessmen were ambitious tinkerers who would recover and repair vehicles—cars, trucks, or buses; anything that could accommodate a few passengers and maintain fairly regular routes to and from the city. In the eyes of the authorities, however, these individual ventures were illegal. Since they had not been licensed by the new government they were deemed to be operating outside the law. But that did not matter to the passengers; they desperately needed transportation to and from the city center. In time the government grudgingly came to tolerate matatus as a necessary evil.

The private businesses lurched along unchecked, despite the government’s grumbling, until 1973, when President Jomo Kenyatta abruptly declared matatus legal. The ruling was a surprise. Even more surprising was the fact that Kenyatta had declined to prescribe any restrictions, or require any form of licensing, on the matatus. It may have been a simple oversight. But by foregoing the chance to regulate the industry he gave the matatu owners de facto permission to explore the limits of laissez-faire capitalism.8 Suddenly everybody wanted in on the action. Unfit vehicles in all states of disrepair began roaming the streets; even more dangerous was the recklessness with which drivers began to operate their rickety rattletraps—bouncing through potholed streets, reeling around corners, the drivers raced through the streets as fast as they could to get first crack at passengers who they then packed in so tightly that arms, legs, and backsides were left hanging out of doors and windows.9

The indifference to safety, along with the government’s regulatory neglect, led to a predictable increase in accidents. In fact, they became so common that newspaper headlines routinely announced the tragedies with a weary shrug. Reporting became jaded: “Another horror matatu crash”; “twenty people perish in another matatu accident”; or, “matatus are a Black Hole of Calcutta.” Not to be outdone by the newspapers’ scoffing unconcern, the owners began emblazoning the sides of the minibuses with slogans that reveled in the matatu’s perils: such slogans as “Coming for to Carry Me Home” or “See You in Heaven” announced the matatu’s dangers with daring cockiness. Owners seemed to have no qualms at all about suggesting to passengers that their next destination might well be the next world. And the passengers, with places to go and no other way to get there, overlooked the odds of an accident.10 If you hopped on a matatu and did not get where you were going, at the very least you would arrive in heaven. Either way, everyone would win.

While this kind of gallows humor no doubt invited a certain cavalier camaraderie, it did nothing to mitigate the risks of actually riding in a matatu. The increasing number of injuries and fatalities made it clear that something needed to be done to make the industry safer. In response to the crisis, President Moi passed a law in 1984 requiring that matatus be inspected and licensed. The new regulations had both good and bad consequences; while the new law clearly helped provide some oversight, it unfortunately ended up curtailing the business by shutting out many of the poorer matatu owners who lacked the means to meet the new safety requirements. The law also ended up helping the wealthier owners, who quickly began to consolidate their power by forming associations; on the other hand, this power grab had the beneficial effect of allowing matatu owners to organize itineraries and thus limit the chaotic overlapping of routes and reduce traffic congestion.11

By the early 1990s, then, the consolidation of operators, along with the corresponding decrease in competition and increased organization of routes, noticeably reduced reckless driving and improved safety. Unfortunately, the associations formed by the well-off owners began selfishly controlling the routes and exacting exorbitant parking fees and “goodwill payments,” thus making it difficult for new owners to enter the business.12 These exclusionary tactics meant that the entry of new owners into the business was no longer a matter of free market choices. Suddenly matatu startups encountered a barricade of byzantine negotiations with key stakeholders over a wide range of social, political, and economic variables—and passing through the barricade typically involved some kind of payoff. If you wanted to be on the streets, you had to be ready to offer a bribe.

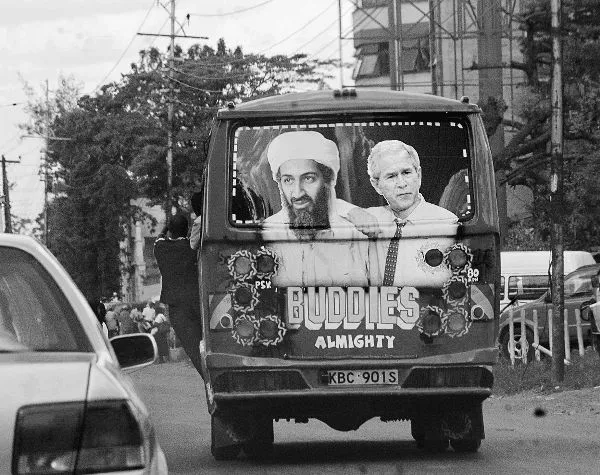

As fewer and fewer owners managed to enter and survive the industry’s consolidation, those who did quickly began to monopolize it. But as bad as this may seem, some of the consequences were beneficial. It was not long before the wealthier owners purchased safer and more comfortable vehicles.13 By the late 1990s, instead of the old, overburdened jalopies, the streets soon entertained new Nissan, Toyota, and Isuzu minivans with ornate paint jobs, air conditioning, and lavish interiors with such luxuries as tinted windows, state-of-the-art sound systems, and eventually flat-screen TVs. Much better than splintery benches bolted to the bed of an old pickup. Still, despite the exclusionary tactics, despite the streamlined routes and all the added comforts, there remained the mad scramble for passengers. So, to lure passengers, matatu operators started to “trick out” their vehicles with blaring hip-hop and flamboyantly painted exteriors—from somber black to a Rubik’s-Cube assortment of colors, or with airbrushed creations normally reserved for movie posters or street murals. Each matatu had to be unique. Particularly popular were the names and portraits of American hip-hop artists like Kanye West, Eminem, Ludacris, Jay-Z, or Snoop Dogg; sometimes they promoted political figures—there were predictable portraits of Barack Obama, that most honored child of Kenya (in one such image he is kissing his wife, Michelle), but you might also encounter such political absurdities as George Bush sitting beside Osama bin Laden. Regardless, the transformation of the matatu was profound. Just a few generations earlier matatu owners had been repurposing used parts to assemble simple vehicles that could carry a few passengers; now, a few decades after independence, they were adorning large, top-of-the-line vans with personalized artwork and high-tech accessories.14

Figure 2 September 2002. Courtesy of the Standard Group, Nairobi

Passengers also changed. They began to expect more creature comforts, a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Dedication

- part one Background

- part two Moving People, Building the Nation, 1960–73

- part three Deregulation, 1973–84

- part four Government Regulation, 1984–88

- part five Organized Crime? 1988–2014

- part six Generation Matatu, Politics, and Popular Culture, 1990–2014

- part seven Self-Regulation, 2003–14

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index