![]()

CHAPTER 1

Evenings at the Opera

“The late king of Poland would pay 100,000 ecus for the performance of each new opera. Spain has displayed a luxury in music whose like cannot be found in all of history. . . . Russia, which had not sounded a note at the beginning of the century, has acquired such a taste for opera that it pays more for an opera singer than a military general.” ANGE GOUDAR, Le brigandage de la musique italienne, 17771

“Here [opera] is for conversation, or for visiting box to box: people don’t listen and they go into ecstasy only for arias.” ABBÉ COYER, Voyages d’Italie et de Holande, letter of January 22, 17642

At the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, Gilda and her father sing the duet from the end of act 2 of Verdi’s Rigoletto. The uproar during curtain calls is deafening, and the Israeli conductor Daniel Oren—a brilliant ham and a great favorite with Neapolitan and Roman operagoers—encores the whole number with little delay. If that were not rare enough nowadays, he then repeats the encore a second time.

Oren’s theatrics are unprecedented in my experience of opera conductors. On this evening, they combine with his quicksilver timing to cause even more commotion than usual, and the Neapolitans match him blow by blow. Not everyone is glad about it. At one point, after the crowd erupts in yet another volcano of bravi, things become too much for one of the highbrows in a lower tier, and after the noise dies down he cries out in spite of himself, “Aspettate almeno che finisca la musica!” (At least wait until the music is over!). His well-heeled Florentine accent sounds a decorous note in a raucous ensemble of cheering, clapping, and stomping—disarmingly so, since these days class in the opera house is more often signaled by the cut of a suit than the tone of the voice. The outburst is one among many that marks the evening as an event. Two days later an incredulous reviewer from the Roman daily La repubblica writes that the evening had a “clima da stadio” (atmosphere of a sports arena), adding that the act 2 duet was encored twice “a furor del popolo.”3

Small wonder he was amazed. Even in Naples, where audiences are reputed to be among the most demonstrative in Italy—certainly more than in northern Europe or America—ambient noise is usually limited to the seating of late comers, the sound of elderly spectators humming along with their favorite numbers, or fans covering the ends of arias with shouting and applause. On this night the public’s behavior put it in dialogue with the performers in a way redolent of reports from the eighteenth century. But there was an ironic difference. Public excitement was ignited from the orchestra pit, through the mediation of a conductor, whose very existence was still relatively novel in Verdi’s time and unknown fifty to a hundred years earlier. That the drama at hand was emanating from the pit was obvious from my box near the proscenium in the sixth tier at the top of the house, the so-called piccionaia (pigeon gallery), which gave an almost perfect view onto the pit. From that vantage point, Oren’s histrionics outdid even those of the famous Leo Nucci, who sang the title role, or the new starlit soprano, Maureen O’Flynn, as Gilda.

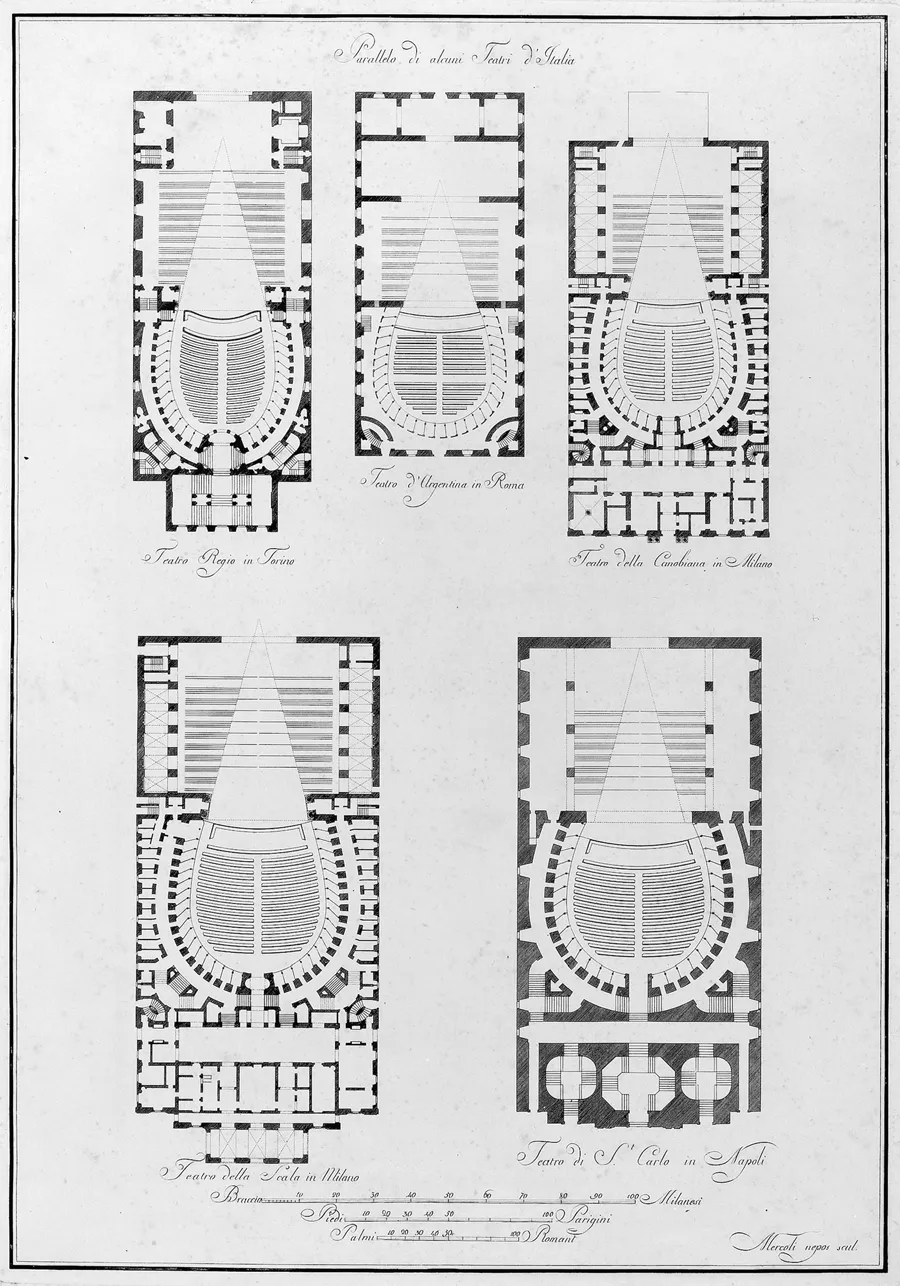

All the same, once activities in the house heated up into the double encore and continued through the last act, it was not just Oren’s conducting but the dynamics of the whole house that played on the audience’s attentions. This reality of collective and reciprocal participation—and the voyeuristic amusement that my bird’s-eye view gave onto it—would have been far less possible in an opera house built to modern specifications, in which most of the seating points directly to the stage. The commercial theaters of the eighteenth century are another matter. Built for large public spectacles utilizing a horseshoe arrangement, most of their seating is disposed in separate boxes, each of which recedes from its front rail to form a deep well, often with an antechamber, leading in turn to the broad inner corridor of the hall. The Teatro San Carlo, erected in 1737, is a classic, if particularly large, exemplar of this type, with boxes stacked up and circling round in curvilinear ribbons, stretching from either side of the proscenium around toward the back of the hall (see figs. 1.1 and 1.2).

Given such an arrangement, any view of the stage is forever fragmented. Good sightlines are hard to come by, and many boxes yield no real view of the stage unless the spectator pulls a chair up to the rail or cranes her neck. From many boxes, viewing the stage continuously requires an ongoing, strenuous effort no matter where one is seated, and nothing is easier than eyeing others across the hall or turning inward to fidget with garments, whisper to friends, stretch out in the back, or fondle a lover.4 A spectator strongly resistant to distractions might yield to them rarely and reluctantly, but will have trouble avoiding them altogether, and a less resistant one can happily succumb. Even people in the parterre who can see the stage head on from seating affixed to the floor are not immune to distractions imposed by the majority inhabiting boxes throughout the periphery.

FIG. 1.1. Teatro San Carlo, Naples, audience awaiting start of performance, ca. 1960s. Photograph from Il Teatro di San Carlo, 1737–1987, ed. Franco Mancini, Bruno Cagli, and Agostino Ziino (Naples: Electa Napoli, 1987), 2:193. Reproduced by kind permission of the publisher.

Events in the San Carlo on that night can help us think about how space mediates feelings and practices in the theater and works to accommodate them. The multiplicity of spaces and sightlines in an eighteenth-century opera house runs counter to modern demands—demands on spectators to view the stage in a state of absorbed silence and demands on musicians to adhere to the dictates of the score. The special way that Oren exploited such a theater made a virtue of this multiplicity, getting the audience to clamor for a command performance.

FIG. 1.2. “Parallelo di alcuni teatri d’Italia.” Engraving showing the varied horseshoe shapes of five eighteenth-century theaters. From Giuseppe Piermarini, Teatro della Scala in Milano (Milan, 1789). By permission of the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

But Oren’s exploits assumed a form that also underscores the gulf between the realities of our time and those of the eighteenth century. None of his encores was done during the opera proper, much less in the middles of acts. Instead, they were initiated after the end of an act, in the forestage in front of the opera curtain while singers were taking their curtain calls. In that time and space the two darlings of the stage—one many years beloved by the public, the other vaunted as its new star—could be relocated to a theatrical borderland at a climactic moment. Facing their admirers in direct address, they had dropped character and become performers, not figures in a drama. Their encores became more like a concert—with Oren as one of its stars—delivered with an alleged spontaneity at the special urging of an adoring public. And the encores were in turn efficacious in consolidating the growing affections between the performers and their fans.

OPERA SERIA, SOVEREIGNTY, PERFORMANCE

This book explores the relationship between “dramma per musica”—known more colloquially, especially in its twilight years, as “opera seria,” as I call it here—and various crises of social and political transformation in eighteenth-century Italy.5 It is not about opera seria per se, but about its reflexive relationship with those transformations, especially as they concern sovereignty in the latter half of the century, when the principal trope of opera seria, elaborating the motif of the magnanimous prince, was colliding with a growing bourgeois public sphere.

Most of today’s opera lovers still know of opera seria from only a few works by Handel (Poro, Giulio Cesare, Rodelinda, Xerxes) and Mozart (Idomeneo and La clemenza di Tito). Names from the 1720s and 1730s like Leo, Vinci, Porpora, Pergolesi, and Hasse, or Traetta, Jommelli, and Galuppi from midcentury, may slip off the tongues of musicologists or connoisseurs but not average music fans.6 Even Cimarosa, Zingarelli, Paisiello, and Mayr, so popular in the late eighteenth century, are far from household names. Scholars of the past knew the genre well, but many found it unintelligible. Yet opera seria reigned supreme among all musical and theatrical genres across most of eighteenth-century Europe.7 Getting to write the music or, even more prestigiously, the poetry for an opera seria was like getting to write a feature for Dreamworks. And as a dramatic form that allegorized sovereignties throughout Europe—from the elector Palatinate to the tsar of Russia, the kings of England, Spain, Prussia, and Sweden (indeed everywhere, save France, which had its own high lyric genre of tragédie lyrique)—it was the genre par excellence of highbrow lyric theaters.8

In Italy, few of those theaters had as direct an association with kingship as the San Carlo, built to celebrate the advent of a new king (indeed a new kingship); yet the San Carlo typified the great commercial opera houses that produced opera seria. Everywhere, whatever forms of rule prevailed, opera seria thrived in the glow of old-regime sovereignty. In this sense, it thrived in a world endlessly marked by the reiteration of social hierarchies whose implications were nothing short of cosmological—implicit assertions of a world order in which ranks cascaded downward in the great chain of being from God to sovereign or ruling class to the various classes and orders below. All the concrete spaces and operations of such theaters were rooted in this fundamental political model, even as some practices put it in doubt. When elite public theaters were not direct outcroppings of a court, as was the San Carlo—attached in 1737 to the royal palace complex, though with its own public entrance (figs. 5.1 and 5.4)—they were invariably overseen by ruling persons or groups: the prince’s superintendent, an aristocratic family, a society of oligarchs, or members of a theater academy. In this respect, opera seria invariably reproduced, as narrative and social/symbolic practice, the prevailing social structure, broadly supporting the absolutist trope of sovereignty despite inflections indigenous to different forms of political organization across Italy: kingships at Naples or Turin, dukedoms at Parma, Modena, and Mantua, oligarchic republics at Venice, Lucca, and Genoa, the papal monarchy in Rome and the Papal States.

Of the fifty or so new serious operas being produced around midcentury every Carnival season (the number including comic genres is much higher), only a fraction used entirely new libretti. Until the early 1780s but even beyond, from one city to another, there was an amazing persistence in the reuse of libretti (usually revised on site), and hence in the presentation and representation of sovereignty. Individual city-states, with their own political forms and civic ideologies, did produce distinct local physiognomies of the genre, but a limited set of narrative archetypes circulated, which were repeatedly set and reset anew and stocked by an absolutist panoply of symbolic tropes and classical references.

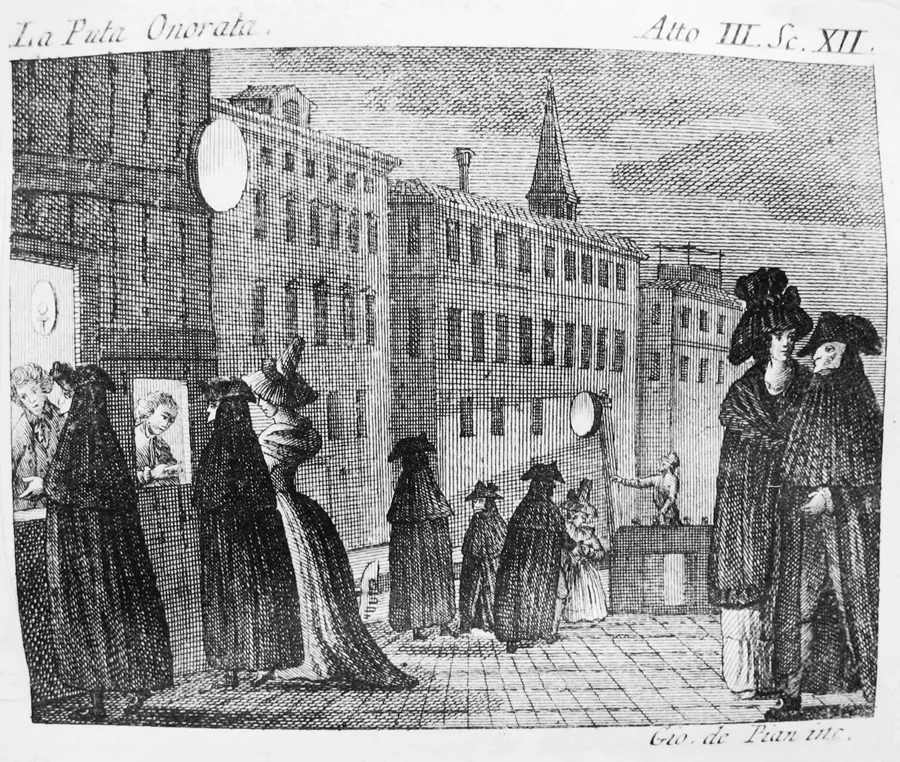

Yet politically, opera seria was a paradoxical beast. In one sense it was a protocapitalist bourgeois form, attended by a mixed populace, including paying customers—some of them social climbing—and managed through various combinations of state, court, and private persons and funds. Among its patrons was a middle class of moderate means consisting of doctors, lawyers, teachers, civil servants, and the like, many of whom bought tickets on a nightly basis because they could not afford the stiff annual costs of seasonal subscriptions or box ownership even when it was permitted to them. (See the frontispiece to a play by Carlo Goldoni in fig. 1.3.) But opera was kept afloat by wealthy patrons, many, but by no means all, aristocrats, who owned their boxes like little landed estates on which they nevertheless paid annual levies. Only if forced by necessity did they pay annually to rent them.9 Along with these wealthy audience members came servants, both liveried servants and servants of a lower order (valets and chambermaids indoors, footmen and coachmen outdoors), who would populate hallways and were sometimes given official admission to the uppermost gallery. Theater workers, including members of the military guard, staffed the corridors, atriums, and passageways of the opera house, and the stalls were populated by military men, students, professors, and other bourgeois intellectuals, some of whom entered on free lists.

FIG. 1.3. Engraved illustration on the opening page of act 3 from Goldoni’s comedy La putta onorata, showing masked theatergoers purchasing tickets at a botteghino (or biglietteria) at the entrance to a theater in Venice. From Carlo Goldoni, Opere teatrali (Venice: Antonio Zatta, 1791), vol. 11. By permission of the Casa Goldoni, Biblioteca, Venice.

Unlike theaters tightly enclosed within a court, commercial opera houses, even when dominated by the aristocracy, thus housed a broad and fluctuating assemblage of competing social positions, which could variously combine to reflect, embellish, substitute for, or undermine a prevailing sovereign person or group. For the upper classes, opera seria was to, for, and about the sovereign(s), but it was also to, for, and about themselves. Who implicitly it addressed was prone to slippage and probably tempered by many factors. How did Prince Artaserse’s dilemma over divided loyalty speak to the Venetian patrician? To the nobleman in Modena in the presence of his duke (or in his absence)? To the Roman abbot who prattled in the shadows of the Teatro Argentina, safe from the governor’s gaze? These kinds of questions have no ready answers. Opera seria rested on new modes of production and new forms of social and political organization that were beginning to eclipse the old quasi-feudal ones. No one person or group could claim its symbolic capital in toto, and the mechanisms of identification were many, varied, and complexly mediated. If opera seria was at root the king’s opera, its relations of production and its sociabilities also tested the king, manifesting the very crisis it denied.

* * *

The period up through the 1780s was one of glory days for opera seria. Despite substantial reforms and shifts in musical and poetic style, especially from the late 1750s onward, opera seria endured in a more or less “classic” form codified during the 1720s, telling tales of heroes, young and old, who make their way through a labyrinth of passions, from jealous desire to filial love, rage, joy, pity, sorrow, remorse, and pi...