eBook - ePub

Rereading the Fossil Record

The Growth of Paleobiology as an Evolutionary Discipline

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Rereading the Fossil Record presents the first-ever historical account of the origin, rise, and importance of paleobiology, from the mid-nineteenth century to the late 1980s. Drawing on a wealth of archival material, David Sepkoski shows how the movement was conceived and promoted by a small but influential group of paleontologists and examines the intellectual, disciplinary, and political dynamics involved in the ascendency of paleobiology. By tracing the role of computer technology, large databases, and quantitative analytical methods in the emergence of paleobiology, this book also offers insight into the growing prominence and centrality of data-driven approaches in recent science.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rereading the Fossil Record by David Sepkoski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Evolution. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2012Print ISBN

9780226272948, 9780226748559eBook ISBN

9780226748580CHAPTER ONE

Darwin’s Dilemma

Paleontology, the Fossil Record, and Evolutionary Theory

Darwin’s Dilemma

It is well documented that paleontological and geological evidence were vitally important to Charles Darwin in establishing his theory of evolution via descent with modification, particularly because the historical evidence of the fossil record enabled him to argue for temporal evolutionary succession of past forms. This first became evident to him during his voyage on HMS Beagle in the 1830s, when he observed the succession of a variety of forms of fossil animals like the giant sloth Megatherium and the armadillo-like Glyptodon along the length of the South American continent. In the first and successive editions of Origin, Darwin devoted many pages to discussing the significance of fossil succession, and it is no exaggeration to say that paleontology formed a major pillar of his argument for evolution. Yet in what appears in retrospect a profound irony, even as Darwin elevated the significance of the evidentiary contribution of fossils, he also had a major hand in condemning paleontology—the newly emerging professional discipline devoted to their study—to the status of a second-class discipline. One of his greatest anxieties was that the “incompleteness” of the fossil record would be used to criticize his theory: that the apparent “gaps” in fossil succession could be cited as negative evidence, at the very least, for his proposal that all organisms have descended by minute and gradual modifications from a common ancestor. Darwin worried that at worst, the record’s imperfection would be used to argue for the kind of spontaneous, “special” creation of organic forms promoted by theologically oriented naturalists whose theories he hoped to obviate. His strategy in the Origin, then, was to scrupulously examine every possible vulnerability in his theory, and as a result he spent a great deal of space apologizing for the sorry state of the fossil record.

Indeed, Darwin devoted an entire chapter to this problem, entitling it “On the Imperfection of the Geological Record.” Even as he made the case that fossil data were vital for a true understanding of organic history, he cited the paucity of transitional forms between species as an inherent and potentially intractable problem for geologists and paleontologists. “We have,” he wrote, “no right to expect to find in our geological formations, an infinite number of those fine transitional forms, which on my theory assuredly have connected all the past and present species of the same group into one long and branching chain of life” (Darwin 1964 301). The metaphor Darwin chose in his apology for the fossil evidence was that of a great series of books from which individual pages had been lost and were likely unrecoverable. “I look at the natural geological record,” he continued, “as a history of the world imperfectly kept, and written in a changing dialect; of this history we possess the last volume alone, relating only to two or three countries. Of this volume, only here and there a short chapter has been preserved; and of each page, only here and there a few lines” (Darwin 1964 310–11).

This metaphor was not Darwin’s own invention; he first encountered it while reading Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, where Lyell wrote:

Let the reader suppose himself acquainted with just one-tenth part of the words of some living language, and that he is presented with several books purported to be written in the same tongue ten centuries ago. If he finds that he comprehends a tenth part of the terms in the ancient volumes, and that he cannot divine the meaning of the other nine-tenths . . . . He must feel at once convinced that, in the interval of ten centuries, a great revolution in the language had taken place. . . . So if a student of Nature, who, when he first examines the monuments of former changes upon our globe, is acquainted with only one-tenth part of the processes now going on upon or far below the surface, or in the depths of the sea, should still find that he comprehends at once the import of the signs of all, or even half the changes that went on in the same regions some hundred or thousand centuries ago, he might declare without hesitation that the ancient laws of nature have been subverted. . . . In truth, there is no part of the evidence in favour of the uniformity of the system, more cogent than the fact, that with much that is intelligible, there is still more which is yet novel, mysterious and inexplicable in the monuments of ancient mutation in the earth’s crust. (Lyell 1830, vol. 1, 461–62)

Darwin recorded his approval of this metaphor in his “Notebook D” of 1838: “Lyell’s excellent view of geology, of each formation being merely a page torn out of a history, & the geologist being obliged to fill up the gaps, is possibly the same with the philosopher, who has [to] trace the structure of animals & plants—he get[s] merely a few pages” (Darwin 1987, 352–53). The metaphor continued to dominate Darwin’s thinking about the evidence of transmutation in the fossil record: in “Notebook E,” begun in 1839 but not completed until 1856, he endorsed Adam Sedgwick and Roderick Murchison’s view of gradational organic change and asked whether “we give up the whole system of transmut[ation], or believe that time has been much greater, & that systems, are only leaves out of whole volumes” (Darwin 1987, 433).

Since the metaphor of the incomplete book clearly had currency in the middle part of the 19th century, the “blame” for its corresponding (and discouraging) message to future paleontologists cannot be laid entirely at Darwin’s door. But it is important to note that in an evolutionary context, the incompleteness of the fossil record takes on enhanced significance. While Lyell eventually accepted transmutation, his Principles assumed that organic form was static, and his geology adhered to the strict uniformitarian view that the conditions and processes of the earth and its inhabitants did not vary greatly over time. Transitional forms were not expected, and if organisms were missing from particular localities or strata where they were expected to be found, Lyell assumed that they were simply waiting to be discovered in some other place. Sedgwick’s case was even easier: as a follower of Cuvier’s “catastrophist” geology, he actually expected gaps to be present in the geologic record, which corresponded to Cuverian “revolutions” or cataclysmic, transformative events.

It was thus only after transmutation came into the picture that the paucity of the fossil record became a significant issue. Darwin’s theory revolutionized paleontology, since the fossil record became a vital source of evidence that evolution had occurred and for interpreting the history of organic change. Darwin’s “dilemma,” however, was that he both needed paleontology and was embarrassed by it. Even as he celebrated the contributions of paleontologists, he simultaneously undercut any claims their emerging discipline might have had for autonomy within evolutionary theory. Without evolution, paleontology made interesting, descriptive observations about the form and distribution of once-living creatures; without paleontology, there was far less evidence that evolution had happened. But on its own, paleontology could offer no independent contribution to evolutionary theory, since that theory depended on evidence from biology, breeding, biogeography, geology, heredity, and other fields in order to make the paleontological data meaningful. In other words, paleontology without the support of evolutionary theory could not decisively settle any questions about the nature of organic history—it required Darwinian evolutionary theory to contextualize its contributions, and at the same time to excuse its flaws. At least, this is how Darwin and many of his immediate supporters consciously or unconsciously framed the situation—and, as we will see, this had a significant impact on the next hundred years of paleontological theory.

Paleontology after Darwin

Of course, Darwin himself had no reason to feel any special guilt about the unforeseen consequences of his attitude towards paleontology. When he was developing his theory of evolution, biology and paleontology had not yet become firmly established as independent disciplines, and as a “naturalist” he simply marshaled and interpreted the available evidence from all fields as they best supported his argument. But the aftermath of the publication of Origin was a period that saw significant disciplinary reorganization, and one result was that scientists became increasingly aware of distinct disciplinary identities. A number of historians have written about the emergence of the experimental tradition in biology during the second half of the 19th century, which contributed greatly to the direction evolutionary study took after 1859.1 In mimicking some of the laboratory practices and methods of established disciplines like physics and chemistry, biologists greatly enhanced the prestige and autonomy of their field. The emphasis in post-Origin biology was on identifying cell structures responsible for heredity (e.g., chromosomes) and studying the physiological processes of biological development (such as patterns in ontogeny; Bowler 1989).

This turn towards biology as a laboratory science indirectly contributed to the formation of a disciplinary identity for paleontology. Darwin had stated, more or less, that paleontology would make limited contributions towards understanding evolution, so for his supporters there was no great urgency to scrutinize the fossil record. In fact, Darwin’s supporters were more likely to want to push paleontology into the background: as William Coleman argues, “To the biologist that [fossil] record posed more problems than it resolved . . . . the incompleteness of the recovered fossil record, in which a relatively full historical record for any major group was still lacking, was the very curse of the transmutationist” (Coleman 1971, 66). As a result, there were really only three alternatives available to paleontologists with regard to evolutionary theory: (1) to ignore any special theoretical relevance of paleontological data and focus purely on descriptive studies of morphology and stratigraphy, (2) to accept the Darwinian position but nonetheless try to improve the quality of the record of isolated fossil lineages to support Darwin’s theory, or (3) to reject Darwinian evolution and seek some other theoretical explanation of evolution in which fossil evidence could be brought more directly to bear.

Over the next hundred years, and perhaps even longer, the majority of working paleontologists tended to take option 1, which was essentially agnostic towards evolutionary theory. This did not mean rejecting Darwin or evolution; it simply meant not attempting to make any direct contribution to illuminating evolutionary patterns and processes. In the early 20th century this attitude became even more prevalent as the burgeoning petroleum industry’s demand for paleontological expertise swelled the ranks of paleontology with scientists whose interest in the field was “economic” (Rainger 2001). Between 1859 and 1900, option 2 probably described the smallest number of actual paleontologists, although a number of naturalists (such as T. H. Huxley) with significant paleontological expertise did contribute paleontological apologia to Darwinism. In the 19th century, paleontology was dominated by vertebrate paleontologists, and paleontological research examining the morphology and anatomy of larger mammals, fish, birds, and dinosaurs was most conspicuous. Certain lineages, such as the early horses, proved to have well-preserved records and provided modest contributions towards validating natural selection. However, among paleontologists with ambition to contribute to evolutionary theory, the most popular option was 3—to explore non-Darwinian evolutionary mechanisms. Lamarck’s theory of directional evolution, in which acquired characteristics could be passed from parents to offspring, remained popular, as did a number of similar theories that attributed directionality to the fossil record. American paleontologists, in particular, were drawn to Lamarckism and to orthogenesis, which tended to assume that “directional” evolutionary patterns—such as parallelism and convergence—reflected an internal evolutionary “guiding force.” Late-19th-century paleontologists’ subscription to these non-Darwinian evolutionary beliefs had the short-term consequence of contributing to what some scholars have termed the “eclipse of Darwin,” but the longer-term and more significant effect was that paleontology isolated itself from what would be the mainstream, Darwinian attitude of evolutionary biologists in the first half of the 20th century (Bowler 1983, chs. 4, 6, 7).2 As Coleman notes, during the late 19th century, “in no discipline did expectations appear so great but frustrations prove so common as in paleontology,” which “as a consequence long maintained most ambiguous relations with orthodox Darwinism” (Coleman 1971, 80).

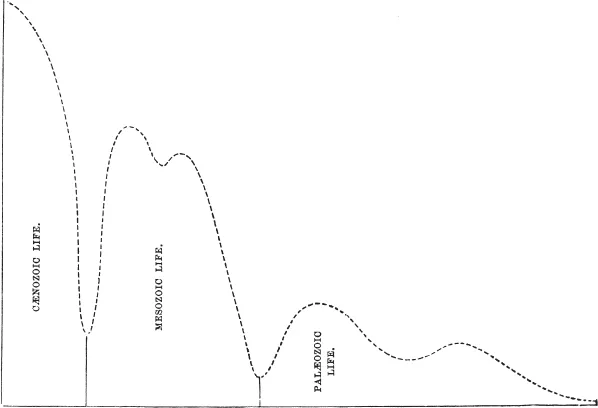

Of course, not every paleontologist in Darwin’s day accepted Darwin’s dismal conclusion about the fossil record or its predictions for the future contributions of paleontology. For example, Darwin’s countryman John Phillips—a paleontologist who conducted the first thorough accounting of the accumulated fossil record and interpretation of its results—strongly disagreed with Darwin’s position. Phillips is remembered today primarily as the inventor of the three great stages in the history of life: the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic eras, which corresponded to discontinuities he observed in the proportions of various major taxa present (or absent) in the succession of the earth’s strata. Phillips depicted the history of life as a series of three, overlapping diversity curves, the first two of which terminate as a new curve begins its ascent (Phillips 1860, 66; fig.1.1). Phillips’s model was ambitious for its time, but he defended its legitimacy in part by criticizing Darwin’s opinion that “we possess . . . merely fragments of the record, which indeed never was complete. . . . Thus we must not expect to be able to arrange the fossil remains in a really however broken series, since the true order and descent may be, and for the most part is, irrecoverably lost.” Rather, he countered, “surely this imperfection of the geological record is overrated. With the exceptions of the two great breaks at the close of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic periods, the series of strata is nearly if not quite complete, the series of life almost equally so” (Phillips 1860, 206–7). Phillips’s approach to the history of life was simultaneously progressive and conservative: it was progressive both in the sense that it argued for the epistemological significance of the fossil record and because it promoted a view of the history of life that was directional—pace Lyell, time’s arrow moved steadily forward, and the fossil record demonstrated irrecoverable changes in the pattern of life’s history (Gould 1987; Rudwick 2005a; Rudwick 2005b). On the other hand, as Peter Bowler has observed, Phillips’s view of progressive change exhibits traces of the “conservative, idealistic philosophies that stood opposed to the liberal image of gradual transformation built upon by evolutionists such as Darwin and Herbert Spencer” (Bowler 1996, 353).

FIGURE 1.1. John Phillips’s depiction of the history of life as three successive diversity curves. John Phillips, Life on the Earth; Its Origin and Succession (Cambridge and London: Macmillan and Co., 1860), 66.

Among Darwin’s supporters, the most outspoken apologist for the paleontological record was probably Darwin’s “bulldog,” Thomas Henry Huxley. While Huxley differed with Darwin about the origin of new types (e.g., higher taxa), he nonetheless defended Darwinian descent with modification using evidence from paleontology (Lyons 1999; Desmond 1982, ch. 3). In his 1870 address to the Geological Society, “Paleontology and the Doctrine of Evolution,” Huxley argued that “it is generally, if not universally, agreed that the succession of life has been the result of a slow and gradual replacement of species by species; and that all appearances of abruptness of change are due to breaks in the series of deposits, or other changes in physical conditions” (Huxley 1894, 343). Huxley emphasized the uniformitarian assumption in this view that “the continuity of living forms has been unbroken from the earliest times to the present day,” and concluded with the Lyellian-sounding proposal that “the hypothesis I have put before you requires no supposition that the rate of change in organic life has been either greater or less in ancient times than it is now; nor any assumption, either physical or biological, which has not its justification in analogous phenomena of existing nature” (Huxley 1893, 343 and 388). In private, however, Huxley was unconvinced that the evolution of higher taxa did not involve some form of saltation, or evolutionary “leaps.” In an 1859 letter he wrote to Lyell that “the fixity and definite limitation of species, genera, and larger groups appear to me to be perfectly consistent with the theory of transmutation. In other words, I think transmutation may take place without transition.” This did not mean that he rejected natural selection, or even that he doubted gradualism, but at least in the year Origin was published he felt the paleontological evidence “lead[s] me to believe more and more in the absence of any real transitions between natural groups, great and small” (Huxley to Lyell, June 25, 1859, quoted in Herbert 2005).

If Darwin’s reading of the fossil record had difficulty gaining traction even among his staunchest allies, it is easy to understand why many paleontologists less ideologically committed to Darwinism felt compelled to pursue an entirely different theoretical approach. There is some truth to the perception that paleontology offered few contributions to evolutionary theory between the publication of Origin and the period of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s, but this interpretation hardly tells the whole story. Many paleontologists did in fact pursue descriptive work in morphology and stratigraphy with very little interest in evolutionary theory, but there was a sizable minority who had genuine theoretical and evolutionary ambitions. This group included a number of prominent late-19th- and early-20th-century paleontologists, including the American vertebrate specialists O. C. Marsh, E. D. Cope, Alpheus Hyatt, H. F. Osborn, W. D. Matthew, and William Gregory, and such European paleontologists as George Mivart, Alexandr Kovalevskii, Othenio Abel, Louis Dollo, Wilhelm Waagen, Karl Alfred von Zittel, and Otto Schindewolf. When in 1944 George Gaylord Simpson published his landmark Tempo and Mode in Evolution, it certainly marked a turning point in terms of paleontology’s reception among evolutionary biologists, but Simpson was hardly sui generis. There were, in fact, a great many paleontologists between 1860 and 1940 who pursued evolutionary theory. The problem was—at least from the perspective of the eventual framers of the modern synthesis—these paleontologists pursued the wrong kind of evolutionary theory.

It is worth taking a moment to consider what, to a paleontologist, the fossil record seems to indicate about evolutionary processes and patterns, and how that interpretation might differ from the perspective of a biologist. As Bowler points out, 19th-century research into systematics was concerned especially with reconstructing fossil phylogenies. This involved arranging fossils into likely sequences based on “structural resemblances” and attempting to extrapolate evolutionary development across morphological and stratigraphic gaps. For this reason, “morphology thus became the first center of evolutionary biology” (Bowler 1996, 41). The problem, however, is that the sequence of morphology in the fossil record does not always clearly indicate the steps in evolutionary sequence taken by a particular lineage. Fossils are often too rare, too poorly preserved, or just plain missing, and it is left to the paleontologist to connect the dots in as likely a fashion as possible. A feature that appears to stand out in the fossil record is the appearance of fairly linear trends, even among distantly or unrelated groups, towards similar morphological features. One example is the phenomenon of parallelism, or the tendency for multiple lines of descent to follow “a more or less identical sequence of morphological stages” after divergence from a common ancestor (Bowler 1996, 70). Another apparent trend is convergence, in which wildly different groups independently settle on the same adaptive response to an environment without the presence of a recent common ancestor (as in the evolution of wings in both birds and bats). The question posed to pa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Rereading the Fossil Record

- CHAPTER 1. Darwin’s Dilemma: Paleontology, the Fossil Record, and Evolutionary Theory

- CHAPTER 2. The Growth of Theoretical Paleontology

- CHAPTER 3. The Rise of Quantitative Paleobiology

- CHAPTER 4. From Paleoecology to Paleobiology

- CHAPTER 5. Punctuated Equilibria and the Rise of the New Paleobiology

- CHAPTER 6. The Founding of a Research Journal

- CHAPTER 7. “Towards a Nomothetic Paleontology”: The MBL Model and Stochastic Paleontology

- CHAPTER 8. A “Natural History of Data”: The Rise of Taxic Paleobiology

- CHAPTER 9. The Dynamics of Mass Extinctions

- CHAPTER 10. Toward a New Macroevolutionary Synthesis

- Conclusion: Paleontology at the High Table?

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index