- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Prior to 1735, South America was terra incognita to many Europeans. But that year, the Paris Academy of Sciences sent a mission to the Spanish American province of Quito (in present-day Ecuador) to study the curvature of the earth at the Equator. Equipped with quadrants and telescopes, the mission's participants referred to the transfer of scientific knowledge from Europe to the Andes as a "sacred fire" passing mysteriously through European astronomical instruments to observers in South America.

By taking an innovative interdisciplinary look at the traces of this expedition, Measuring the New World examines the transatlantic flow of knowledge from West to East. Through ephemeral monuments and geographical maps, this book explores how the social and cultural worlds of South America contributed to the production of European scientific knowledge during the Enlightenment. Neil Safier uses the notebooks of traveling philosophers, as well as specimens from the expedition, to place this particular scientific endeavor in the larger context of early modern print culture and the emerging intellectual category of scientist as author.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Measuring the New World by Neil Safier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2008Print ISBN

9780226733623, 9780226733555eBook ISBN

9780226733562ONE

The Ruined Pyramids of Yaruquí

The works of Bouguer and La Condamine have had an extraordinary (singulière) influence on the Americans from Quito to Popayan. The ground of this land has become classic . . . The Audiencia of Quito was able to destroy the Pyramids, but they were incapable of drowning the spark of genius that rises up from time to time in this land, and that shines brightly along the trail that Bouguer and La Condamine have blazed.

ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT (1802)

I will dwell in solitude amidst the ruins of cities; I will enquire of the monuments of antiquity, what was the wisdom of former ages: I will ask . . . what causes have erected and overthrown empires.

CONSTANTIN FRANÇOIS CHASSEBOEUF DE VOLNEY (1791)

All they could discuss were Pyramids: the word alone awakens great ideas.

LA CONDAMINE, HISTOIRE DES PYRAMIDES DE QUITO (1751)

The luminous constellations of the Southern Hemisphere shone brightly overhead as the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt stood in silent reverie on a highland plain near Quito. As he eagerly scoured the heavens for signs of a passing comet on this March night in 1802, he recalled the stunning panoramas through which he had passed earlier that day. Images of the majestic snow-capped volcanoes of the Andean cordillera—Cotopaxi, Illiniza, Corazón, Pichincha—glowed in his memory like fading beacons against the evening sky. Turning his gaze to the Southern Cross and finding its nebulous core darker and more beautiful than he had ever observed, Humboldt used the opportunity to reflect on the inscrutability and opacity of human knowledge. The visual senses could only perceive a mere fraction of the universe’s boundless matter, and Humboldt seemed to throw up his hands at the enormity of the task before him: “[H]ow many things exist,” he wrote in his personal journal, “that man cannot see.”1

As if humbled by the profundity of his own reflections, Humboldt turned the next morning to less celestial concerns: visiting the destroyed remnants of a pyramid that had been erected nearby as a monument to European science. Trampled fragments of broken marble tablets, shards of a broken fleur-de-lis made of ash-green porphyry stone, illegible inscriptions formed with Latin characters, and discarded cube-shaped stones employed as pedestals were the vestiges he found scattered about at the farm of Oyambaro. Like the French traveler Constantin de Volney who sojourned among the decaying monuments of Egypt, Humboldt saw in these Andean ruins evidence for the rise and fall of civilizations. But where Volney saw only the downfall of territorial empires, Humboldt saw the demise of the human spirit as well. As he sifted through the rubble picking up various “astronomical relics” as souvenirs, he marveled at history’s destructive hand and shuddered at the forces that ravaged such objects of human ingenuity. “We might imagine ourselves among the Turks,” he wrote, “when we find the most important monument to the progress of the human spirit ransacked before us.”2 To Humboldt, the state into which this ruined pyramid had fallen reflected a mysterious and unpredictable encounter between the aspirations of human culture, the destructive power of nature, and the fleeting character of historical memory, like a brilliant meteor that burns its path across the darkest sky and then just as quickly disappears from view.

These decrepit structures on the plain of Yaruquí had been built to function as permanent markers of an astronomically determined baseline, but instead they stood out rather ironically as symbols of decay. Half a century before a broken fleur-de-lis caused Humboldt to reflect on the “vicissitudes” of scientific memory, an intrepid and inventive astronomer from France had managed to persuade others that pyramids would be suitable monuments to scientific achievements. Charles-Marie de La Condamine had arrived in Yaruquí with an ingenious plan, having left behind a culture in which monuments were performative and theatrical gestures were part and parcel of intellectual life.3 He and the rest of his colleagues had come to South America not to read demurely from the book of nature; they wanted to be the scribes that wrote and performed their own entrance onto the scientific stage. In the words of one of La Condamine’s colleagues, South America would be “a vast theater . . . which few or none duly qualified to make observations have as yet seen, or travel’d over.”4 The French savants wanted this South American laboratory for geometric triangulation to be their own performative space, where they would serve as the playwrights, actors, designers, and directors of a scientific drama unveiled in print.

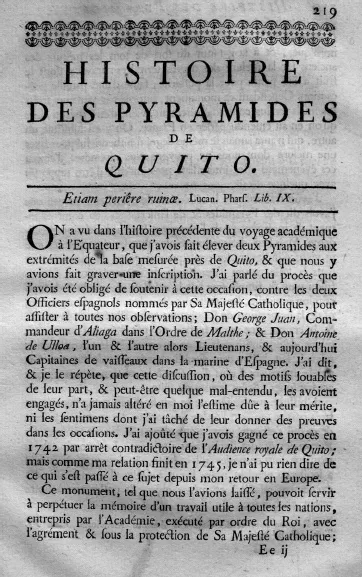

In order to build this performative theater of science at the very site of their operations, La Condamine worked assiduously to transform the raw materials of the Andean landscape into monumental “texts” inscribed with his own heroic and empirical accomplishments. And of the many sites onto which he inscribed his achievements, none was more symbolic than the pyramids at Yaruquí. Affixed permanently at either end of the academicians’ northern baseline, these monuments were to serve as material markers of transcendental truths (plates 2 and 3). Each tetrahedral pyramid would sit upon a square base of between five and six feet in height, constructed from rocks taken from nearby ravines and covered in a brick exterior, also of local confection. An inscription carved in marble stone would then be affixed to one of the four faces, and a 4-by-6-inch inscribed silver plate inside a sealed box was to be lowered down into each pyramid to protect it from eventual mutilation or theft. What La Condamine was unable to foresee, however, was that the pyramids would eventually be destroyed, not only by those whom he disparagingly referred to as “people from the neighborhood” (gens du voisinage) but also by those who had authorized their construction in the first place. In the wake of their destruction, La Condamine would nonetheless profit from their demise by publishing an account where his own authorial talents came to the fore, and in which he would claim proprietary rights over the expedition’s achievements by suppressing the accomplishments of others who had assisted and supported his work. The Histoire des pyramides de Quito (1751) was the result (fig. 3).

La Condamine’s narrative account of the construction of the Quito pyramids emerges out of a context in which members of eighteenth-century scientific academies began to see themselves as authors as well as academicians, seeking to lay claim to their own intellectual rights by publishing accounts in which their actions and ideas took center stage.5 To recount the history of the pyramids, La Condamine used symbolic, material, and linguistic strategies, fashioning himself as the conceptual and practical foreman of a project in which physical monuments functioned as markers of intellectual, if not territorial, hegemony. The pyramids were not only a literal imposition of European architectural and scientific codes onto the Latin American landscape. They also effectively erased the contributions of those who had assisted in their construction. The attempt to commemorate the results of the Quito expedition thus brought into sharp relief the ways in which Europeans accommodated themselves and their projects to local conditions; in this case, they sought to make a plain near Quito conform to the universal aspirations of Enlightenment science.6

Figure 3. La Condamine’s Histoire des pyramides de Quito (1751) recounted a dispute over the construction of two pyramidal monuments at the base of the academicians’ measurements near Quito. The citation from Lucanus’s Pharsalia, “Even the ruins perished,” is ironic, since the account for which it serves as epigraph guaranteed that the controversy lived on well after the physical monuments themselves had been destroyed. Courtesy of the Special Collections Library, University of Michigan.

This moment also signaled an important transition between a period in which great achievements were commemorated on the spot through construction and inscription—a carryover from earlier traditions that saw the construction of monuments as an homage to individual monarchs or deities—and the more modern procedure of setting down the results of scientific experiment through published works. Humboldt believed that mountains would make more lasting monuments than pyramids. The volcano of Cayambé that straddled the equator near Quito was in his words “one of those eternal monuments by which nature has marked the great divisions of the terrestrial globe.”7 For Humboldt, empirical science should follow suit in using these sites as markers of scientific truth. But La Condamine knew that monuments to individual achievement had symbolic value as well, especially since they could be forged out of local materials and captured iconographically in print. The inscription of scientific results onto the American landscape would thus provide a visual referent that could accompany published texts and treatises. And as a historical symbol of permanence and stability, the pyramid was the ideal choice to commemorate the mission’s activities on a highland Andean plain.

Sturdy Symbols

As a young man, La Condamine had front-row seats for learning about science as a performative art. While in Paris in the late 1720s, he regularly attended the informal salon at the Café Procope, which was presided over at the time by the flamboyant dramaturge Antoine Houdart de La Motte. Later, Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis took the reins, an astronomer with whom La Condamine would collaborate throughout his career and whose encouragement and support may have facilitated La Condamine’s entrance to the Academy of Sciences in 1730. His close friendship with Voltaire may have been a factor encouraging his theatricality as well, since this was one of Voltaire’s most active periods as an author of drama, much of which seemed redolent of themes and locations dear to La Condamine. But perhaps improvisational drama was merely in La Condamine’s blood. Voltaire told of an evening at the home of Charles-François Cisternai du Fay in which a young La Condamine, recently returned from an expedition to the Levant, had disguised himself as a Turk. He then proceeded to beguile those in attendance about his “Oriental” origins. In a letter to Maupertuis, Voltaire commented that “whenever [Maupertuis] wished to have another dinner at the home of M. du Fay with the honest Muslim who speaks such excellent French,” he would be happy to comply.8 Following Voltaire’s return from exile in England, during which time he had become a vocal advocate for Newtonian science, the two friends conceived and carried out a brilliant scheme to defraud the French treasury of large sums of money. For anyone willing to make the massive initial investment, La Condamine had realized with devious mathematical prowess that the poorly designed lottery would pay out more money than it actually took in. They bought up as many tickets as they could, and enriched themselves greatly as a result.9

This image of La Condamine as a trickster and deceiver did not always go over well at the Academy, however. Indeed, following his death, Condorcet wrote that La Condamine’s curiosity and need to be constantly active “made all prolonged meditation impossible, preventing him from going deeply enough into any scientific area to arrive at any new discoveries.”10 Likewise, Jacques Delille conceded that La Condamine’s knowledge was perhaps “more extended than profound.” But both were quick to acknowledge the merit of La Condamine’s career within the context of eighteenth-century culture: “[I]f others have made more sublime discoveries in philosophy,” Delille wrote, “none has left a greater example for the philosophe.”11 And in what was perhaps the most perspicacious assessment of La Condamine’s theatrical and literary talents, Condorcet provided an explanation for what had allowed the errant astronomer to so successfully mold opinions to his favor:

[La Condamine was] widely known in every society, possessing the art of persuading the ignorant people to whom he had listened, bringing back singular observations to pique the frivolous curiosity of the gens du monde, writing with enough charm (agrément) to have people read his work, with enough neglect and too simple a tone to foster envy or threaten the self-esteem of others, interesting for his bravery and piquant for his faults.12

The “art of persuasion” and ability to “pique the frivolous curiosity” of his European colleagues were skills that were honed throughout La Condamine’s career.13

The Turkish disguise he had used for the practical joke on Voltaire and Maupertuis was likely a prize from his first voyage as a member of the Academy. La Condamine established his reputation by accompanying an expedition to the Mediterranean and the Levant only a year after being offered membership. This early experience melding travel writing and scientific observation provided a basis for his later writings in South America and undoubtedly influenced the Academy of Sciences to choose La Condamine to participa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Preface: The Ascent of Francesurcu

- Introduction: New Worlds to Measure and Mime

- Chapter 1: The Ruined Pyramids of Yaruquí

- Chapter 2: An Enlightened Amazon, with Fables and a Fold-Out Map

- Chapter 3: Armchair Explorers

- Chapter 4: Correcting Quito

- Chapter 5: A Nation Defamed and Defended

- Chapter 6: Incas in the King’s Garden

- Chapter 7: The Golden Monkey and the Monkey-Worm

- Conclusion: Cartographers, Concubines, and Fugitive Slaves

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index