eBook - ePub

Sound Knowledge

Music and Science in London, 1789-1851

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sound Knowledge

Music and Science in London, 1789-1851

About this book

What does it mean to hear scientifically? What does it mean to see musically? This volume uncovers a new side to the long nineteenth century in London, a hidden history in which virtuosic musical entertainment and scientific discovery intersected in remarkable ways.

Sound Knowledge examines how scientific truth was accrued by means of visual and aural experience, and, in turn, how musical knowledge was located in relation to empirical scientific practice. James Q. Davies and Ellen Lockhart gather work by leading scholars to explore a crucial sixty-year period, beginning with Charles Burney's ambitious General History of Music, a four-volume study of music around the globe, and extending to the Great Exhibition of 1851, where musical instruments were assembled alongside the technologies of science and industry in the immense glass-encased collections of the Crystal Palace. Importantly, as the contributions show, both the power of science and the power of music relied on performance, spectacle, and experiment. Ultimately, this volume sets the stage for a new picture of modern disciplinarity, shining light on an era before the division of aural and visual knowledge.

Sound Knowledge examines how scientific truth was accrued by means of visual and aural experience, and, in turn, how musical knowledge was located in relation to empirical scientific practice. James Q. Davies and Ellen Lockhart gather work by leading scholars to explore a crucial sixty-year period, beginning with Charles Burney's ambitious General History of Music, a four-volume study of music around the globe, and extending to the Great Exhibition of 1851, where musical instruments were assembled alongside the technologies of science and industry in the immense glass-encased collections of the Crystal Palace. Importantly, as the contributions show, both the power of science and the power of music relied on performance, spectacle, and experiment. Ultimately, this volume sets the stage for a new picture of modern disciplinarity, shining light on an era before the division of aural and visual knowledge.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sound Knowledge by J. Q. Davies, Ellen Lockhart, J. Q. Davies,Ellen Lockhart,James Q. Davies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Music as an Object of Natural History

Emily I. Dolan

They sung their strains in notes so sweet and clear

The sound still vibrates on my ravished ear.

—Dante, translated by Charles Burney

Charles Burney’s Travels

We begin with an echo. On July 21, 1770, Charles Burney laughed and shouted; he instructed a trumpet to be blasted and a pistol and musket to be fired. His rowdy noisemaking was part of a sonic investigation: Burney was stationed in the outskirts of Milan, at the Villa Simonetta, built in the mid-sixteenth century for Ferdinando Gonzaga. A visitor who went to a particular window on the top floor, one that looked out over the courtyard, could experience a remarkable effect: single sounds reverberated loudly thirty or even fifty times. Athanasius Kircher first discussed the echo in the ninth book of his Musurgia universalis (1650) and later returned to the topic in his Phonurgia Nova (1673), explaining in detail how the architecture created the conditions for this phenomenon. The echo gained fame over the course of the eighteenth century, and by the nineteenth century the villa was a must-see destination. Burney’s visit was just one stop of many during his travels in France and Italy, which he had begun in June 1770, to gather material for a forthcoming General History of Music. He published an account of his travels in 1771 and the following year undertook further travels through Germany and the Netherlands, publishing a second report in 1773. The first of the four volumes of his history appeared in 1776; the final volumes were published in 1789.1

Burney admitted he had “expected exaggeration” when he visited the echo but had been wrong. He did not attempt—as Kircher had—to explain the physical basis for the phenomenon (“This is not the place to enter deeply into the doctrine of reverberation,” he wrote). Rather, he was concerned with sonic effect, declaring, “as to the matter of fact, this echo is very wonderful.” He continued:

Such a musical canon might be contrived for one fine voice here . . . as would have all the effect of two, three, and even four voices. One blow of a hammer produced a very good imitation of an ingenious and practiced footman’s knock at a London door, on a visiting night. A single ha! became a long horse-laugh; and a forced note, or a sound overblown in the trumpet, became the most ridiculous and laughable noise imaginable.2

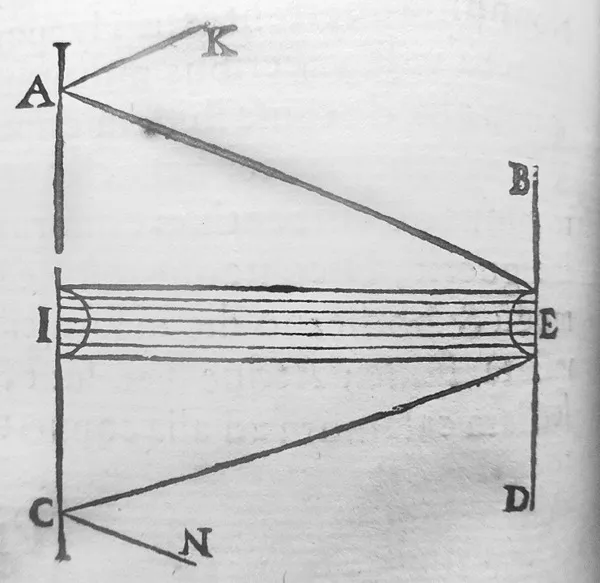

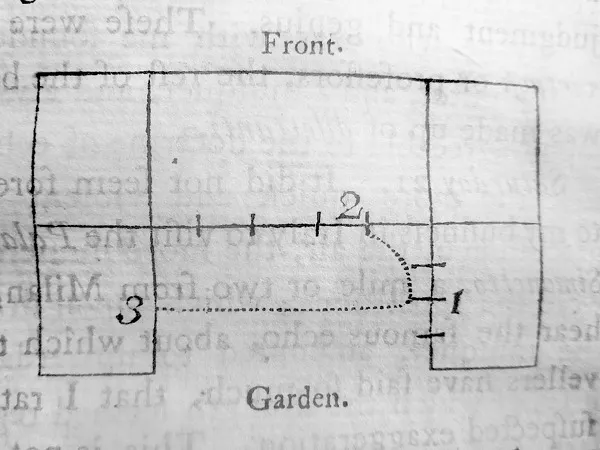

The differences in approach of Kircher and Burney reflect in part a fundamental change in what the study of sound implied: for Kircher, music was a branch of mixed mathematics, and unsurprisingly his description is a geometric account of the felicitous proportions of the courtyard (see figure 1.1). Burney’s investigation was less concerned with the principles of acoustics; rather, he was interested in the experience of echo, and his lively description allows readers to be virtual witnesses—or virtual auditors—of that experience (see figure 1.2).3 Central to Burney’s description is the notion of effect, here understood as phenomena that produced special or notable bodily reactions. This move from a mathematical to an experiential account is significant. Burney’s description of the Villa Simonetta is indicative of a more general shift in the eighteenth century toward aesthetic modes of inquiry into music and—more generally—music’s burgeoning autonomy as a discipline and object of knowledge.

Figure 1.1. Image from Athanasius Kircher’s Musurgia Universalis, book 9 ([Rome: Francisci Corbelletti, 1650], 290) demonstrating how sound bounces repeatedly from one wall to the wall opposite. (Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

Figure 1.2. Charles Burney’s diagram showing the key spots in the Villa Simonetta: “1. The best window to make the experiment at. 2. The best window to hear the echo. 3. A dead wall with only windows painted upon it, from whence the repetitions seem to proceed.” (The Present State of Music in France and Italy [London: T. Becket, 1771], 99. Jean Gray Hargrove Music Library, University of California, Berkeley.)

Burney’s motivations for visiting and describing the villa are not obvious. After all, it could be construed as not immediately useful to his conception of musical history and thus an indulgent digression. When in 1832 the English magazine the Harmonicon published a short biographical sketch of Burney’s life, his trips were framed as doggedly and single-mindedly focused on one purpose:

He resolved to make a tour of Italy and Germany, determined to hear with his own ears and see with his own eyes; and, if possible, to hear and see nothing but music. For although he might have amused himself enough in examining pictures, statues, and buildings, it was necessary he should economize the little time he could afford to be absent himself from England; and he could not indulge in general observation without neglecting the chief business of his journey.4

One could argue that the villa formed part of the sonic landscape of Milan and that Burney’s travels were far ranging and all-encompassing: he saw organs and military bands, street musicians and opera. In other words, Burney may indeed have focused on “nothing but music,” but his definition of music was considerably broader than we might expect. However, a brief glance through either one of the travel diaries reveals the Harmonicon’s panegyric to be pure fantasy. Burney’s investigation of the echo at the Villa Simonetta was one of many interests that lay beyond the musical: in the midst of trips to opera houses, churches, salons, and concert halls, he visited a number of laboratories and observatories of physicists and astronomers, describing what he witnessed with the same lively enthusiasm that he used on musical visits. Indeed, at the end of his second tour he wrote, “If my leisure and abilities would have sufficed for so extensive a plan, I should have been glad to make the journal of this tour, the present state of arts and sciences, in general.”5

In what follows, I argue that Burney’s approach was radical—though in ways that are invisible now. This essay explores two ways in which a view of Burney’s engagement with documenting science expands our understanding of the particular way in which he approached music. First I consider instruments, the ideas of experiment, and the ways Burney emphasized technical detail and performative effect; second, I turn to the idea of natural history, which was a “universal donor” to various facets of eighteenth-century culture.6 My aim is to describe, on the basis of both Burney’s travels and the evidence of his history of music, what sort of thing—what sort of object of knowledge—music was understood to be.

Charles Burney, Astronomer

For anyone interested in the intersections between music and science, Burney is an obliging subject. He was an amateur astronomer: in October 1769, shortly before he embarked on his travels to collect materials for his history, he published An Essay towards a History of the Principal Comets that have Appeared since the Year 1742. Since the early eighteenth century, interest in matters astronomical had surged; in Burney’s memoirs, the period is described as “a moment when astronomy was the nearly universal subject of discourse.”7 This expansion reflected the growth of popular science, but was also indicative of new technological developments such as the spread of refracting telescopes, which enabled more accurate celestial observation. Many new phenomena were thus unveiled: James Bradley discovered the nutation of the earth (the wobble caused by the moon’s gravitational pull); in the 1730s, Pierre Maupertuis proved that the planet was oblate and not, as Jacques Cassini had predicted, prolate (that is, the earth’s polar axis is shorter than its equatorial axis). Other celestial phenomena were highly celebrated: the transits of Venus in 1761, for instance, were of enormous importance because they could be used to determine the longitude of particular locations.8

Comets were an especially exciting topic. In 1705, astronomer Edmond Halley had speculated that the famed comets of 1456, 1531, 1607, and 1682 (the last of which he observed himself) were in fact the same comet, and he predicted that it would return in 1758. In 1758, this arrival was awaited with great anticipation—and some trepidation, since comets were in this period still seen as signs of impending disaster. By Christmas Day of that year there had been no sighting, and all hope was almost lost; but then it appeared, causing a sensation. With the aid of better telescopes, new comets were being discovered yearly. Burney’s ninety-three-page booklet was not, as his biographer Roger Lonsdale and others have suggested, motivated by the return of Halley’s comet, but rather by the appearance of a new comet in 1769, one that the French astronomer Charles Messier had discovered.9

In 1789, after Burney completed his history of music, he again turned to the stars, beginning a poem on the history of astronomy. In 1797, while recovering from the death of his second wife Elizabeth the year before, his daughter Fanny encouraged him to return to the project and increase its scope. He imagined a lengthy project entitled Astronomy, an historical & didactic Poem, expected to fill twelve books. He shared his verses with his friend, the famed musician-astronomer William Herschel. Herschel offered both advice and support to Burney on his project:

He gave me the greatest encouragement; said repeatedly that I perfectly understood what I was writing about; and only stopped me at two places. . . . The doctrine he allowed to be quite orthodox . . . he told me—that he had never been fond of Poetry—He thought it to consist of the arrangement of fine words, without meaning—but when it contained science and information, such as mine (hide my blushes!) he liked it very well.10

A fragment of the poem runs as follows:

The various Orbs, pow’r & wisdom plann’d,

Which float in Aether by divine command;

The Laws immutable by wch they run

In never-ending circles round the sun;

The distance, magnitude, & motion’s laws,

Derived from Nature’s Lord, the great First cause;

The Sages who with toil essay’d to find

The emanations of the Mighty Mind;

The means they’ve us’d in science to excel,

The Astronomic Muse essays to tell.11

Burney never completed his “historical & didactic poem”—he ended up committing eight completed volumes to the flames, finding that not all of his readers were as enthusiastic as Herschel. In 1965, Lonsdale rejoiced in what he perceived to be their mediocrity, setting the trend for the subsequent reception of Burney’s poetic works. H. C. Robbins Landon, for example, felt no hesitation in slighting them, writing of Burney’s Verses in praise of Haydn’s arrival in England that “Dr. Burney was many things: a good ‘scholastic’ composer, a brilliant historian, and a man of much taste, learning, and wit. A poet he was not.”12 However, we should not too hastily dismiss Burney’s poetic output: his verses on Haydn, and his astronomical poem, sought to mix education and pleasure, to delight as well as to inform. In this, they partook of a venerable tradition of didactic poetry that stretched back to antiquity.

Jesuit scholars, for example, often published poetic works alongside their dissertations. Both forms were a means of disseminating knowledge. As Yasmin Haskell has argued, the reader of such verses has to invest emotionally in order understand them, thus participating actively in discovery.13 Such work exercises the reader’s intellect while simultaneously appeal...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Fantasies of Total Description

- 1. Music as an Object of Natural History

- 2. Celestial Mechanisms: Adam Walker’s Eidouranion, Celestina, and the Advancement of Knowledge

- 3. Transparent Music and Sound-Light Analogy ca. 1800

- 4. Charles Wheatstone: Musical Instrument Making, Natural Philosophy, and Acoustics in Early Nineteenth-Century London

- 5. Charles Wheatstone’s Enchanted Lyre and the Spectacle of Sound

- 6. Instruments of Empire

- 7. Good Vibrations: Frankenstein on the London Stage

- 8. Engine Noise and Artificial Intelligence: Babbage’s London

- 9. Hearing Things: Musical Objects at the 1851 Great Exhibition

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- Index