eBook - ePub

Abstraction in Reverse

The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American Art

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Abstraction in Reverse

The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American Art

About this book

During the mid-twentieth century, Latin American artists working in several different cities radically altered the nature of modern art. Reimagining the relationship of art to its public, these artists granted the spectator an unprecedented role in the realization of the artwork. The first book to explore this phenomenon on an international scale, Abstraction in Reverse traces the movement as it evolved across South America and parts of Europe.

Alexander Alberro demonstrates that artists such as Tomás Maldonado, Jesús Soto, Julio Le Parc, and Lygia Clark, in breaking with the core tenets of the form of abstract art known as Concrete art, redefined the role of both the artist and the spectator. Instead of manufacturing autonomous art, these artists produced artworks that required the presence of the spectator to be complete. Alberro also shows the various ways these artists strategically demoted regionalism in favor of a new modernist voice that transcended the traditions of the nation-state and contributed to a nascent globalization of the art world.

Alexander Alberro demonstrates that artists such as Tomás Maldonado, Jesús Soto, Julio Le Parc, and Lygia Clark, in breaking with the core tenets of the form of abstract art known as Concrete art, redefined the role of both the artist and the spectator. Instead of manufacturing autonomous art, these artists produced artworks that required the presence of the spectator to be complete. Alberro also shows the various ways these artists strategically demoted regionalism in favor of a new modernist voice that transcended the traditions of the nation-state and contributed to a nascent globalization of the art world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Abstraction in Reverse by Alexander Alberro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunst Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Concrete Art and Invention

Concrete art acquaints humans with things rather than with the fiction of things.

Arte Concreto Invención, 19461

The world of dialectical materialism, which is at the heart of the philosophy of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, guides and confirms our attempts to formulate a materialist and concrete aesthetics.

Tomás Maldonado, 19462

Art world inequality and its relations of dominance provoke their own forms of struggle, rivalry, and competition. But the subjugated here have also developed specific strategies that can be understood only in an art framework, although they may have political consequences. Forms, innovations, movements, and stylistic developments may be diverted, captured, or annexed in attempts to overturn existing art power relations, especially by artists and critics who view their art systems as confined and impoverished in their particularity. For this reason, to speak of European or North American modernism as a colonial or imperial inheritance imposed on artists within subordinated regions is to overlook the fact that modernism itself, as a common value of the spaces of modernity, is also an instrument which, if taken possession of, can enable artists—especially those with the fewest resources—to disrupt the naturalization of the local, the particular, and the national, and to attain a type of freedom, recognition, and existence within it.

It is in these terms that I will analyze the advent of Concrete art in Latin America in the mid-twentieth century. How to explain the fact that this movement, which was appropriated by a handful of young artists who began their careers in Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Caracas, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro, could have turned the entire tradition of Latin American art on its head? Enthused by Concrete art well after it had made its mark in Europe, these artists carried out an astonishing operation, which can only be called a commandeering of artistic power and prestige: they imported into Latin American art itself the very procedures, themes, vocabulary, and forms developed by the Europe-based Concrete artists.3 This usurpation was asserted quite explicitly. The diversion of this power and prestige toward inextricably artistic and political ends was not, then, carried out in the passive mode of reception, and still less of influence, as traditional art-historical analysis would have it. On the contrary, this capture was the active form and instrument of a complex struggle. To combat the largely parochial attitudes of the local ruling oligarchy in their homelands, these young Latin Americans openly asserted the artistic domination exercised by European modernism at the time. Concrete art in particular was used by the artists that are the focus of this chapter as the weapon in their art world struggles.

The initial concepts and terminology of Concrete art were the products of discussions among artists in Paris in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The regular meetings of painters, sculptors, and musicians such as Piet Mondrian, Georges Vantongerloo, Luigi Russolo, Jean Arp, Sophie Täuber-Arp, and Antoine Pevsner prompted Uruguayan painter Joachín Torrés-García to cofound the Cercle et Carré (Circle and Square) group in 1929.4 It was under this programmatic name that in April 1930 the association presented a large exhibition of nonfigurative art in Paris, featuring paintings, sculptures, and architectural models by an international array of artists.5 The exhibition and the review of the same name published by Belgian writer Michel Seuphor created a context whereby the plastic elements of geometric abstract art could be self-reflexively interrogated. But the chronicle ran for only three issues, and with its termination the movement also fell apart.

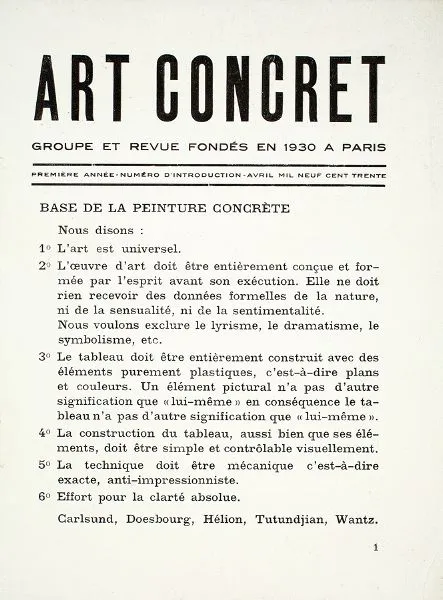

In May 1930, artist and theorist Theo Van Doesburg, who had maintained distance from the Cercle et Carré group and did not participate in its defining exhibition, launched yet another periodical: Art Concret.6 The journal functioned as the official organ of a constellation of geometric painters and sculptors who identified themselves as Concrete artists. The group did not amount to much, and the run of Art Concret ended with the first issue. But with it Van Doesburg introduced the notion of Concrete art.

The “Concrete Art Manifesto” (1930), and particularly the short essay, “Comments on the Basis of Concrete Painting,” that Van Doesburg wrote to supplement it (both are published in Art Concret), pointedly differentiate the term concrete from abstract7 (fig.1.1). The manifesto consists of six numbered points. The first proclaims art’s universality. The second and third call for the priority of the cognitive over the sensual and declare all traces of the natural world to be outside of art’s purview. The artwork is to be constructed only from material elements, “purely plastic elements,” such as planes, lines, and colors. A pictorial element has “no other meaning than what it is by ‘itself.’”8 The last three points call for a simple and precise art characterized by clarity.

In his outline of the basis of Concrete painting, Van Doesburg elaborated on these points: “In their search for purity artists were obliged to abstract from natural forms in which the plastic elements were hidden, in order to eliminate natural forms and to replace them with artistic forms. Today the idea of artistic form is as obsolete as the idea of natural form. We establish the period of pure painting by constructing spiritual form.” Van Doesburg used the term spiritual to mean “mental” or “ideational,” to signify invention, the conception of entirely new forms: “Creative spirit becomes concrete. We speak of concrete and not abstract painting because nothing is more concrete, more real than a line, a color, a surface.”9 Whereas abstraction, for Van Doesburg, is negation, a withdrawal from reality, Concrete art assumes that reality eludes adequate representation and therefore must be constructed.

Figure 1.1 Front page of Art Concret (Paris), 1930. Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University. Photo: John Blazejewski.

Van Doesburg also sharply distinguished between representation of the natural world and the presentation of plastic forms and colors, highlighting the gap that exists between the two: “A woman, a tree, a cow; are these concrete elements in painting? No. A woman, a tree and a cow are concrete only in nature; in painting they are abstract, illusionistic, vague and speculative. However, a plane is a plane, a line is a line, and no more or no less than that.”10 In other words, pictorial elements—lines, colors, forms—have less to do with a cow, a tree, or a figure in the natural world than with building a language of form, which is the language of the picture itself. Rather than referring to some overt subject matter, even if that reference is cast in the mode of abstracting a motif of some kind in the world down to its component parts or its basic elements, the idea is that the basic elements are in place and they can now be built into something else. The painting represents through its arrangement of these elements, which, in all of their artifice and construction, replace the matter-of-fact object in the natural world.

Van Doesburg cast the artwork as an independent entity, as something that produces its own effects, which are intellectual rather than emotional. The notion of the lines, colors, and planes themselves doing the work lies at the heart of Concrete art. This led him to call for Concrete and not abstract painting, with the concrete defined as “clear, intellectual means of expression” capable of being presented in a material way: means of expression, on the whole, that the intellect uses in its (dialectical) attempt to come to terms with the empirical world. Thus Van Doesburg presents Concrete art as wholly derived from idealist philosophy—as an art that tries to bridge the (unbridgeable) gap between the cognitive and the phenomenal by establishing a dialogue, not between the human mind (which he refers to as “spirit”) and the physical world, but between the mind and the means available to communicate its thought and contents. The achievement of Concrete art is that it overcomes the natural constraints of the physical world by the human mind/spirit. Ideas are translated into a pictorial language. The Concrete artwork exists as a whole in consciousness before it is translated into materials; thus “its production must reveal a technical perfection equal to that of the concept.”11 That execution—that concretization of thought—is Concrete art’s central concern. As Van Doesburg explains: “Only thought (intellect), which doubtless possesses a speed superior to that of light, is creative. . . . We use . . . intellectual means.”12

Much can be said about Van Doesburg’s comments on Concrete art. But for the moment I want to emphasize that in elaborating on the attributes of the universal idiom of Concrete art, Van Doesburg separates the idea or mental scheme from the material object that is the pictorial realization of that idea. The prerequisite for the artwork is the intellectual design, he argues, which is then brought to realization with the appropriate pictorial means and, where necessary, the aid of mathematics and other sciences. “Clarity,” he writes, “will serve as the basis for a new culture.”13 By “clarity” Van Doesburg means the revelation of the true content of art, a harmony discovered by the mind and subsequently exemplified through the arrangement of the very simplest pictorial elements. The graphic marks, hues, and planes of a Concrete painting are therefore not merely a result of pictorial formation but also a means of rendering visible abstract and conceptual processes, schemes, and ideas. The latter can be pictorially illustrated to good effect by geometric or other mathematically derived forms: “Everything is measurable, even spirit with its one hundred and ninety-nine dimensions. We are painters who think and measure.”14

Concrete Art

Following the disintegration of Cercle et Carré and the premature death of Van Doesburg in early 1931, Belgian painter Georges Vantongerloo in May 1931 attempted to coalesce an international constellation of nonobjective artists under the umbrella term Abstraction-Création, Art non-figuratif.15 Stylistically tolerant and equipped with their own journal, Abstraction-Création (published in Paris), this loose grouping of artists grew quickly and exponentially and became the center around which abstract art hovered in the early 1930s.16 As the association’s official statutes specify, the goal is “the organization, in France and abroad, of exhibitions of non-figurative art commonly referred to as Abstract art, that is to say works which neither copy nor interpret nature.”17 Exhibitions were assembled in a number of European cities, and the work of these artists had a considerable impact on younger artists and ambitious institutions.18 The periodical, published in Paris five times a year between 1932 and 1936, features programmatic statements and manifestos as well as illustrations of work by affiliated artists. Abstraction-Création thus provides a glimpse of the wide array of nonfigurative pictorial and sculptural tendencies practiced in that decade.

With its stronghold in Paris, in the 1930s the notion of Concrete art was propagated in a number of exhibitions and publications.19 The Swiss artist and architect Max Bill began to theorize his work as “Concrete art” in the mid-1930s.20 Bill had studied at the Bauhaus at Dessau between 1927 and 1929 with Lázló Moholy-Nagy, Wassily Kandinsky, and Josef Albers, and had been affiliated with Abstraction-Création in the early 1930s. During this period he befriended Vantongerloo, whose experiments with painting and sculpture Bill considered to be “beyond what appears to be the frontier of aesthetic existence at the time.”21 In 1936 Bill published a programmatic statement of the principles of Concrete art in the catalogue for the exhibition Zeitprobleme in der Schweizer Malerei und Plastik (Current Problems in Swiss Painting and Sculpture).22 Bill’s clear definition of Concrete art is an endorsement and an incentive. Concrete art, he explains, is by virtue of its special character an independent entity. It is fully distinct from nature. A product of the human intellect and intended only for intellectual contemplation, it should be of that incisiveness and unequivocality that can be expected of the human mind.23

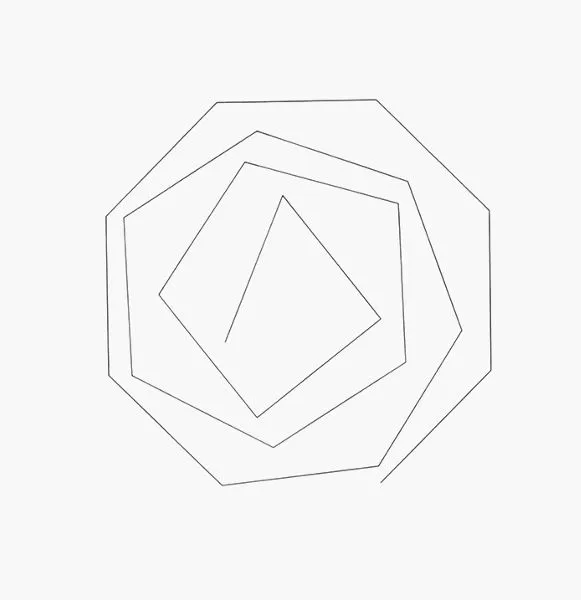

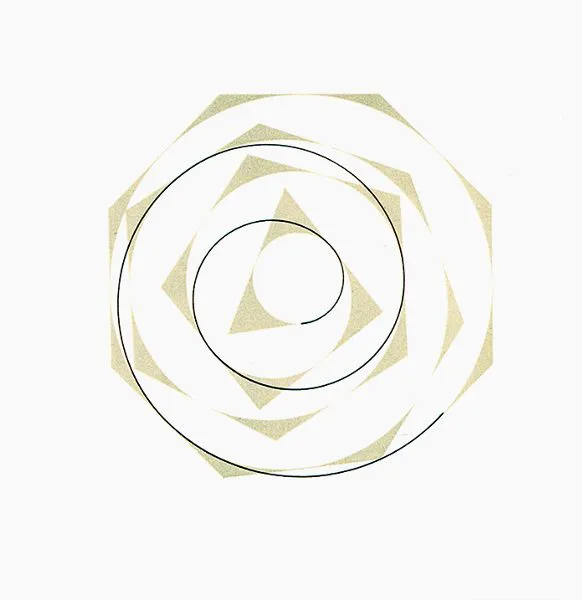

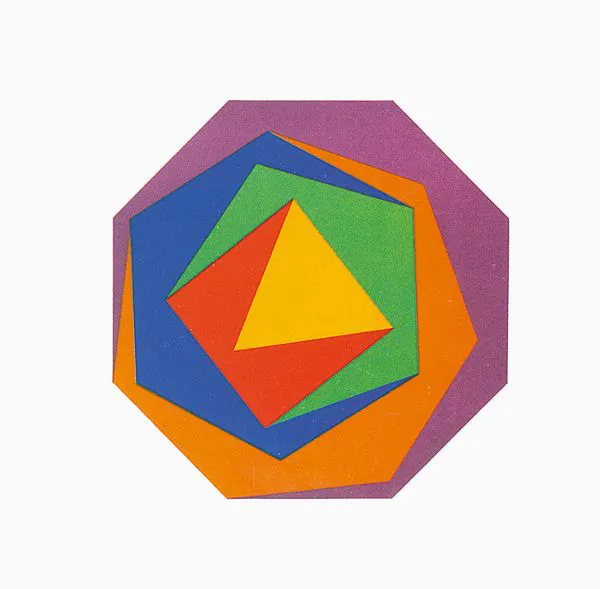

Bill elaborated on practical issues concerning the production of Concrete art in the text accompanying the 1935–38 portfolio of lithographs Quinze variations sur un même theme (Fifteen Variations on the Same Theme). With the method of Concrete art, he writes, “once the basic theme has been chosen—whether it be simple or complex—an infinite number of very different developments can be evolved according to individual inclination and temperament.”24 Fifteen Variations on the Same Theme adopts as its compositional principle a preconceived mathematical scheme based on size and number and formal variations of basic elements. It features the continuous, systematic development of an equilateral triangle into a regular octagon (fig.1.2). Rather than closing the figure, the third side of the triangle is progressively shifted outward to form one of the sides of what will eventually become an octagon. In this way the originating figure of the triangle remains open and is merely suggested. The transitions from one polygon to the next are all made in the same fashion. The resultant figure is a spiral composed of straight lines of equal length. The angles and the areas between these lines show a great variety of form and tension, while an intuitively derived process of transformation (determined by “individual inclination and temperament”) counterbalances the logical rigor of the mathematics. “There are so many possible variations within these narrow boundaries,” Bill writes of Fifteen Variations on the Same Theme, with so many different possible combinations, some of them of diametrically opposed character, “that this by itself proves that Concrete art harbors an infinite number of possibilities.”25

Figure 1.2 Max Bill, Fifteen Variations on a Single Theme, 1935–38. Four panels of a sixteen-part work. © 2015 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ProLitteris, Zurich.

Much of Bill’s painting and sculpture of the late 1930s and 1940s works with basic mathematical schemes or problems. In texts such as “Die mathematische Denkweise in der Kunst unserer Zeit” (The mathematical approach in contemporary art) of 1949, Bill even describes Concrete art’s systematic exploration of abstract concepts as functioning as an aid to mathematics, which have advanced to a point at which many of its ideas are difficult to envision.26 Concrete art’s concern, he writes, is with making the formal “laws of structure” (defined as “sequence, rhythm, progression, polarity, regularity, the inner logic of process and construction”) visually perceivable.27 Like mathematics, Concrete art is a universal language that claims to make logical conceptions, ideas, and abstract thought visible and intelligible in concrete f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Spectatorship after Abstract Art

- 1 Concrete Art and Invention

- 2 Time-Objects

- 3 Subjective Instability

- 4 The Instituting Subject

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index