eBook - ePub

Scenescapes

How Qualities of Place Shape Social Life

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Let's set the scene: there's a regular on his barstool, beer in hand. He's watching a young couple execute a complicated series of moves on the dance floor, while at the table in the corner the DJ adjusts his headphones and slips a new beat into the mix. These are all experiences created by a given scene—one where we feel connected to other people, in places like a bar or a community center, a neighborhood parish or even a train station. Scenes enable experiences, but they also cultivate skills, create ambiances, and nourish communities.

In Scenescapes, Daniel Aaron Silver and Terry Nichols Clark examine the patterns and consequences of the amenities that define our streets and strips. They articulate the core dimensions of the theatricality, authenticity, and legitimacy of local scenes—cafes, churches, restaurants, parks, galleries, bowling alleys, and more. Scenescapes not only reimagines cities in cultural terms, it details how scenes shape economic development, residential patterns, and political attitudes and actions. In vivid detail and with wide-angle analyses—encompassing an analysis of 40,000 ZIP codes—Silver and Clark give readers tools for thinking about place; tools that can teach us where to live, work, or relax, and how to organize our communities.

In Scenescapes, Daniel Aaron Silver and Terry Nichols Clark examine the patterns and consequences of the amenities that define our streets and strips. They articulate the core dimensions of the theatricality, authenticity, and legitimacy of local scenes—cafes, churches, restaurants, parks, galleries, bowling alleys, and more. Scenescapes not only reimagines cities in cultural terms, it details how scenes shape economic development, residential patterns, and political attitudes and actions. In vivid detail and with wide-angle analyses—encompassing an analysis of 40,000 ZIP codes—Silver and Clark give readers tools for thinking about place; tools that can teach us where to live, work, or relax, and how to organize our communities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Scenescapes by Daniel Aaron Silver,Terry Nichols Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2016Print ISBN

9780226356990, 9780226356853eBook ISBN

97802263570411

Setting the Scene

A group waves their hands across a storefront window as motion-sensing devices play music to their movements. Down the street, a few dozen enthusiasts have an impromptu outdoor paint fight. Upstairs in a dive bar pool hall, droning electronica plays amid flashing lights while people with brightly colored hair and tattoo-covered arms eat vegan food. This is not the Latin Quarter, Greenwich Village, or Haight-Ashbury. It is East Toronto. Similar scenes exist in many other cities.

Yet these scenes of indie art, cafes, and electronic music are not the only ones. In bucolic Ave Maria, Florida, all roads lead to a central cathedral and the coffee shop TV is tuned to Mass. The Village, near Vallejo, California, transforms scenes from the paintings of Thomas Kinkade into an urban aesthetic promising “calm, not chaos. Peace, not pressure.” Celebration, Florida, evinces a Disney Heaven of safety and cleanliness. Scenes like these, and many others, are part of our everyday social environment. They factor into crucial decisions, about where to work, where to open a business, where to found a political activist group, where to live, what political causes to support, and more. How, why, and how much? This book provides tools for thinking about these questions, and some answers.

“Scene” as the Aesthetic View of Place

This book is about scenes, what they are, where they are, why they matter. “Scene” has several meanings. One usage emphasizes shared interest in a specific activity: the “jazz scene,” the “mountain climbing scene,” and the “beauty pageant scene.” Another highlights the character of specific places, typically neighborhoods or cities: the “Haight-Ashbury scene,” the “Wicker Park scene,” and the “Nashville scene.”

Our approach to “scene” extends these first two meanings, seeking a more general level of analysis. As a first step on this analytical ladder, think about a neighborhood as a film director, painter, or poet might. There are people doing many things, sitting in a cafe, entering and exiting a grocery, milling about after a church service, cheering the home team. Then ask what style of life, spirit, meaning, mood, is expressed in all of this. Is it dangerous or exotic, familial or avant-garde? How could others share in that spirit, experience and embrace its meaning sympathetically, or reject it? What, in other words, is in the character of this particular place that links to broader and more universal themes?

The Simple Ability to Perceive and Participate in Scenes Contains Remarkable Complexities

This third meaning—the aesthetic meaning of a place—is our focus. It implies a way of seeing that we are all familiar with to some degree. Different places feel different. You can see the differences pass by as you walk, or bike, or drive (slowly, with the windows down) around most any city. Here, fashionable people in high-end restaurants are getting ready for a museum gala or film opening—a glamorous scene. There, families in blue jeans are setting up picnic tables in a park for a barbecue—a neighborly scene. The list could go on, and it will, in later chapters.

Yet however familiar and intuitive such scenes are, they are quite remarkable in a number of ways that are worthy of reflection: namely, in that (1) they are possible at all, that we can coordinate our behavior based on them; (2) we can recognize and differentiate among them; and (3) they matter for things we care a lot about, like why some people and places are more economically successful than others, among other things. Let us consider each of these in turn, as they structure the chapters that follow.

Embedded Meaning Makes Scenes Possible

For the first, how scenes are possible at all, think about what happens when something goes wrong. Imagine for a moment two different scenes.

One is in a jazz club. The lighting is dark, glasses are clinking, smoke is in the air, people are talking, the band is playing and joking with the crowd between sets, cocktail waiters and waitresses artfully dodge around the tables, black-light paintings line the wall, and the audience spills out into the street, where groups stand smoking cigarettes and eating food from a nearby takeout.

The other is a classical music performance. The audience sits up straight, silent absent the occasional cough, wearing suits, ties, and formal gowns; the orchestra, in black and white, sits at stiff attention following the conductor’s cues; fragile chandeliers hover overhead; and all are surrounded by architecture that evokes neoclassical temples, designed to provoke awe and reverence.

Now imagine a mistake: a musician hits a wrong note or plays during a rest. What happens in the jazz club? Chances are the other musicians continue to play. The “wrong note,” while unintended, is a kind of welcome surprise. It interrupts usual improvisational habits, and the musicians launch into a new key, a new time signature, that they had not expected. The audience cheers, and afterward, the “offending” musician takes a special bow, all have a laugh and pour another round of drinks.

And during the classical performance? If a New York Philharmonic violinist accidentally played during the pauses in the great duh-duh-duh-duh theme in Beethoven’s Fifth? The audience would gasp, the offender’s face would go beet red, and if the show did not stop right then, as soon as it was over, he or she would be looking for a new line of work. Critics would write about the horror of the experience.

How do people know how to respond appropriately in such different scenes? It is somewhat amazing. Likely few audience members would have met before. Especially in a big city, they will be from different regions, ethnic backgrounds, ages, and so on. To be sure, the musicians know each other better, and their training may lead them to expect certain things from one another. But take the same jazz musicians and put them in a classical performance, or in a wedding ceremony for that matter, and watch much of their “jazziness” be replaced by more formal standards. Put classical musicians in a crowded bar and watch the reverse occur.

We know how to respond to the situation appropriately partly because something in the situation tells us how to do so. Think again of the jazz club and the Beethoven concert, of what is going on not only in the venues but also outside and around them. The whole situation, from the movement of the waiters to the design of the building, from the nearby restaurants to the posture of the musicians, conspires to “say” things about how to behave: “Be ready for a surprise, express yourself!” in the jazz scene; “Follow established forms elegantly, with refinement and grace!” around the concert hall. Messages, or mantras, like these are written into the situations through which we routinely move, encoded in our streets and strips. They make phenomena like “scenes” possible. Chapter 2 explores these multiple meanings of scenes in more detail.

Aesthetic Intuition plus the Transformation of Desires into Activities and Amenities Makes It Possible to Recognize Different Scenes More Clearly

And here is a second remarkable feature of scenes: we can recognize their subtle aesthetic differences, often without much ado. For instance, in Toronto, scenes with an offbeat, avant-garde feel (think pop-up art galleries and indie rock clubs) are near others with a more glamorous, exhibitionistic, uninhibitedly flamboyant ambiance (think nightclubs and velvet ropes). Separated by only a few hundred yards, participants in both scenes tend to have similar demographic and educational profiles. Yet these scenes can be experienced as separate worlds—a difference marked linguistically when the indie-hipsters brand the clubbers as “905ers,” somewhat sneeringly imputing to them a suburban area code.

Similarly strong aesthetic and cultural distinctions recur elsewhere. We make them all the time, often without any explicit or official markers. Some cities do try to formally define their scenes. Chicago under Mayor Daley II installed distinctive sculptures and icons for different neighborhoods, even rocket-shaped towers with rainbow stripes for its gay neighborhood, Boystown. Many cities post signs like “Entertainment District” or “Chinatown” to flag what type of scenes to expect there.

But by and large these official signs merely recognize formally scenes that are already known. The “real” scenes spill out over the official signage. Their “true” characters are more complex, and sometimes more in dispute.

Still, the differences are there, and we see them. How? Partly because we are not only “cognitive” creatures. We also react to distinctive aesthetic cues. We perceive the world not only as neutral facts and data, but also as full of value-charged objects about which we render judgments: a beautiful sunset, an ugly smokestack, an inspiring skyline, a tacky strip mall.

The philosopher Immanuel Kant pioneered in identifying this aesthetic component of mental life in his aptly titled Critique of Judgment. It has been a recurrent, if often subterranean, theme in psychology and social science, but seldom addressed explicitly. Perhaps the key figures here are the Gestalt theorists.

Two of their ideas are crucial for understanding scenes. First are what they called “affordances.” The idea is that things “afford” certain responses; they “call out” to us. A door handle “asks” to be turned; a set table “invites” us to sit and enjoy a meal.

Second is the idea of “the Gestalt” itself. We see and understand elements of our world holistically, rather than summing the component parts. If we see a tree, for example, we do not see branches, then leaves, then a trunk, and then add all those things together in our minds to make a tree. Instead, we see the tree as a complete entity.

The various elements of the situation, that is, come to us in some kind of totality, where each part fits, like each stroke of a painting. This means that, while things “afford” certain responses, what they “say” varies situationally. The “same” gesture acquires different meanings in different contexts. In one situation, a raised hand is a friendly greeting. In another, it is an act of aggression.

While these abilities to take in the holistic meaning of a scene and to respond to the behavioral cues embedded in objects may be in some sense hardwired into our mental architecture, they are also clearly subject to historical and social variation and refinement. Anthropologist Grant McCracken lists “fifteen ways of being a teenager in North America in 1990: rocker, surfer-skater, b-girls, Goths, punk, hippies, student government, jocks, and on and on.” Economic historian Deidre McCloskey compares this to the 1950s: “You could be mainstream or James Dean. That was it” (McCloskey 2006, 26). This expanding multiplicity of styles is not written in nature, even if the potential may in some sense be genetic.

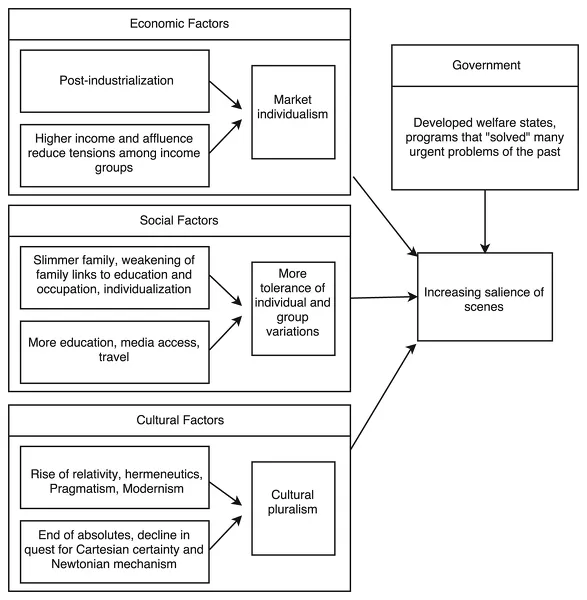

Historical and social changes into the twenty-first century—some of which are summarized in figure 1.1—have rendered more persons more sensitive to subtle aesthetic differences, which have become more sharply delineated in day-to-day experience. The great economist Alfred Marshall outlined the general logic. He called it the transformation of “wants” into “activities.” By “wants” Marshall meant basically what we would today call “preferences.” These are, so to speak, in your head (or heart, or gut—somewhere internal), such as desire for comfort and security. But “wants” can also include the wish to have a home that is not cramped but somehow elevating. Or to live near friends who stimulate you and give you a sense of intimacy and warmth.

Figure 1.1

For most persons through most of human history it has been difficult to realize many if not most of their wants, or even to clearly distinguish among them. Growing general affluence, safety, health, education, and mobility change this drastically, as do the declining, or at least less automatic, influence of the extended family, of the Company Man, of traditional religion, and the concomitant rise of various types of relativisms in culture, science, and spirituality, from Picasso, to Einstein, to Esalen.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Setting the Scene

- 2 A Theory of Scenes

- 3 Quantitative Flânerie

- 4 Back to the Land, On to the Scene: How Scenes Drive Economic Development

- 5 Home, Home on the Scene: How Scenes Shape Residential Patterns

- 6 Scene Power: How Scenes Influence Voting, Energize New Social Movements, and Generate Political Resources (with Christopher M. Graziul)

- 7 Making a Scene: How to Integrate the Scenescape into Public Policy Thinking

- 8 The Science of Scenes (with Christopher M. Graziul)

- Notes

- References

- Index