eBook - ePub

Children of the Land

Adversity and Success in Rural America

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A century ago, most Americans had ties to the land. Now only one in fifty is engaged in farming and little more than a fourth live in rural communities. Though not new, this exodus from the land represents one of the great social movements of our age and is also symptomatic of an unparalleled transformation of our society.

In Children of the Land, the authors ask whether traditional observations about farm families—strong intergenerational ties, productive roles for youth in work and social leadership, dedicated parents and a network of positive engagement in church, school, and community life—apply to three hundred Iowa children who have grown up with some tie to the land. The answer, as this study shows, is a resounding yes. In spite of the hardships they faced during the agricultural crisis of the 1980s, these children, whose lives we follow from the seventh grade to after high school graduation, proved to be remarkably successful, both academically and socially.

A moving testament to the distinctly positive lifestyle of Iowa families with connections to the land, this uplifting book also suggests important routes to success for youths in other high risk settings.

In Children of the Land, the authors ask whether traditional observations about farm families—strong intergenerational ties, productive roles for youth in work and social leadership, dedicated parents and a network of positive engagement in church, school, and community life—apply to three hundred Iowa children who have grown up with some tie to the land. The answer, as this study shows, is a resounding yes. In spite of the hardships they faced during the agricultural crisis of the 1980s, these children, whose lives we follow from the seventh grade to after high school graduation, proved to be remarkably successful, both academically and socially.

A moving testament to the distinctly positive lifestyle of Iowa families with connections to the land, this uplifting book also suggests important routes to success for youths in other high risk settings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children of the Land by Glen H. Elder Jr.,Rand D. Conger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Rural Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9780226212531, 9780226202662eBook ISBN

9780226224978PART ONE

Rural Change and Life Chances

Rural Iowa has been damaged the most by changing economic winds. While not broken, the rural fiber has been stretched until vacant store fronts, lost jobs, dwindling population, and decaying small towns dot the rural scene.

Editorial, Times Citizen, Iowa Falls, 1992

It’s been hard for a lot of our families these last years and I don’t see it really getting any better. Things that you want to buy take more income all the time, and the income doesn’t go up. As a family, we really have to support each other a lot. And help out in whatever we do. We have plumbers, electricians. So that’s a help. We do most of the building or anything like that. The community has scholarship programs for the young. And the church helps out—it’s just good to know you are supported by people who care.

Older citizen, local community, 1994

CHAPTER ONE

Ties to the Land

Iowa is about the land and nature and people taking pride in what we do with our lives.*

D. Shribman, winter, 1996

As we edge closer to the twenty-first century, American families and young people continue to leave agriculture as they have during past decades. A century ago, most Americans had ties to the land through their own lives and those of immediate kin. Now only one in fifty is engaged in farming, and little more than a fourth live in rural communities.1 This historic movement off the land has been driven by many factors, but especially by technological advances that have markedly enhanced productivity. More recently, global economic competition has reduced the profit margin of farm products and undermined rural wages.2 The growing appeal of urban commerce is weakening the vitality of local commerce, adding more incentives for young people to seek their future in urban centers.

In these diverse ways, a new world has come to the rural Midwest at century’s end, to its families and children—a world in which members of the younger generation must seek a future outside of agriculture, with few exceptions, and often in distant places. A new world foretells new lives among those who make their way in it. The story of such change, of new lives in a new world, is recorded in patterns and trends, yet rural communities continue to rely upon the resourcefulness of a small number of farm families, their leadership, social involvement, and economic resources.

Are resourceful pathways for rural young people associated in any way with the social resourcefulness of families, especially of families still engaged in farming? To answer this question, we focus on rural Iowa, a region that suffered mightily in the Great Farm Crisis of the 1980s. The state lost a higher proportion of its citizens through outmigration than any other midwestern state across the decade. The number of farms has declined significantly since the 1960s, and the average surviving farm has grown in size. Most Iowans in the last century operated farms. Today little more than one-tenth run farms, though most rural Iowans have some connection to agriculture. Despite this change and the correlated economic hardship of rural communities, Iowa’s children continue to rank among the very best on school success indicators compared to children in other states.

The historic economic problems of family farming were magnified by the 1980s Great Farm Crisis that hit the American Midwest with a force that will long be remembered. It was, indeed, the Great Depression all over again. By the mid-1980s, the Iowa landscape was littered with the casualties of this crisis, symbolized at times on courthouse lawns by a white cross for each lost farm. Across the countryside, seventy-five banks had closed, plus several hundred retail stores, and some fifteen hundred service stations.3 By the early 1990s, the construction industry was still down by40 percent from the late 1970s. Businesses had boarded-up windows, and “for sale” signs appeared on the main streets of towns across the state. Good jobs and employment of any kind were difficult to find in small towns. Prompted by such limitations, people began leaving rural counties at a rate as high as 20 percent during the decade. The entire state lost nearly 5 percent of its population during the 1980s. Everyone knew someone who had left for other places, but especially young people.

Population losses of this magnitude posed drastic consequences for rural communities. The economic cost was most obvious in terms of declining jobs, sales, and taxes. An Iowa businessman noted that he had “watched business after business after business go out. We’ve lost industry. There hasn’t been anything left unaffected by this.”4 Mounting social costs also threatened the quality of community life, as in the breakdown of families, a reduction of students for the local school, and the loss of parents to provide leadership in civic, church, and school associations and functions. Many rural communities had to abandon local schools through consolidation and experienced the financial crises of local stores, churches, and social services as well. As in other times and places, the young people who left home were typically among the most able.

These economic and social costs are particularly evident in the departure of farm families, the economic and social foundation of rural life. Farm families generate the critical social capital, the relationships and working arrangements, that make communities desirable places in which to live and raise a family.5 They are typically characterized by shared goals and common activities. Parents and children in farm families do more activities together, in the family and centered in the community, than do urban families. Farm children are also counted on to a greater extent—they are more involved in activities that other family members value and rely upon. Children and young people on family farms are expected to do their part. Such an environment is likely to produce the discipline and competency necessary for a successful life.6

Farm families in the Midwest frequently assemble in community associations to achieve common goals, such as a stronger school system, an effective youth group, or improved roads and health care. The typical farmer belongs to several voluntary associations or cooperatives.7 Leadership for the common good is a responsibility of farm families, in particular, and such actions satisfy norms of social obligation and stewardship. In these rural farm communities, effective social relations among people who have contact with children represent social capital that fosters personal qualities of competence.8 Adults with working relationships of mutual trust can share observations about children and enforce norms and goals. Social engagement for community goals is especially common among farm families such as those of German ancestry in which generational succession is important,9 a prominent cultural theme of rural midwestern communities.

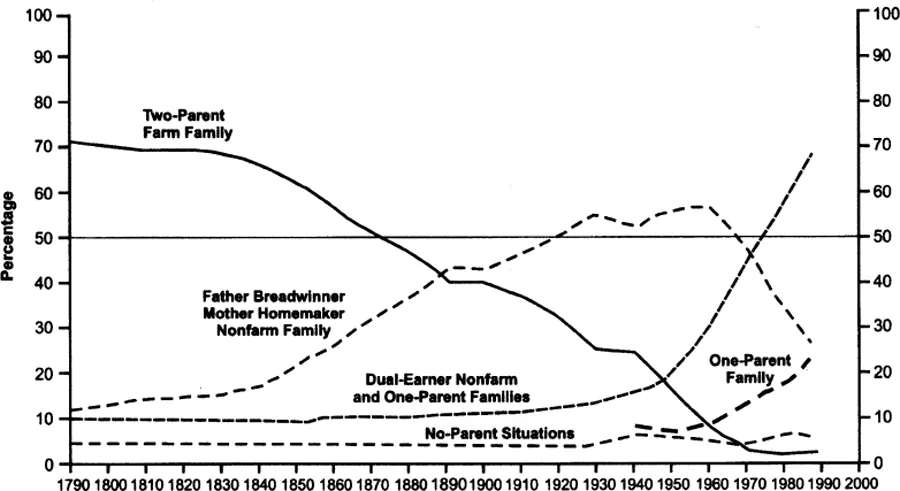

With these qualities in mind, some observers question whether rural depopulation will alter our national character. “What about the beliefs and value systems that have been associated with life on the land? Will Americans be able to establish an acceptable value system that rests on life in cities, perhaps symbolized by concrete and neon lights?”10 Is the rapidly shrinking number of farm families symptomatic of a great transformation in which social resources are becoming scarcer in the lives of children?11 Are there fewer people in rural America who care for children in nurturant families, who know their friends and the parents of these friends? This loss means that social control is less effective in children’s lives, reflecting an absence of adult consensus on things that matter. These questions have special relevance when we note the striking decline of two-parent farm families over the past century and a corresponding increase in the prevalence of divorce and one-parent households (figure 1.1).

The decline of families with ties to agriculture threatens the survival of an accustomed quality of life in rural communities that dot the open countryside, for young and old, children, parents, and grandparents. However, the quality of life at the community level may be placed at even greater risk when industrialized farming takes over. The long-term effects of this economic system tend to “limit future economic potential wherever it is found.”12 Low wages, impoverished schools, and civic passivity are coupled with a siphoning of local wealth. Industrialized agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley of California has degraded the environment, and its practice of recruiting imported labor “has tended to weaken and impoverish communities and to divide them along class and ethnic lines.”13 In Iowa, industrialized farming in the form of corporate contracts is most evident in hog factories that pollute the water, soil, and air.

Figure 1.1 Children in Farm Families, 1790–1789.

Sources: Census PUMS for 1940–1980, CPS for 1980 and 1989, and appendix 4.1 in America’s Children.

Note: Percentages are plotted for children aged 0–7 in father-as-breadwinner families and in dualearner families; estimates are for 10-year intervals to 1980, and for 1989. Reprinted with permission from Donald Hernandez, America’s Children, © 1993, Russell Sage Foundation, New York, NY

This book is based on the rural life experiences of Iowa children who were born at the end of rural prosperity in the postwar era, a time that extends up to the late 1970s. They grew up in the north central region, experienced the Great Farm Crisis of the 1980s, whether through their own families or others, and now face a world transformed. We focus on children with family ties to the land, ranging from full-time farming to farm-reared parents and parents without a farm background. With an eye on routes to life success rather than failure, we investigate the extent to which successful development is linked to the social resources or capital of families with ties to the land. The study follows children in these families from the seventh grade through junior high school to high school graduation, a time of important life decisions on employment, further education, and social relationships.

We view the proposed sequence of family ties to the land, social resources, and adolescent competence within a framework of generational succession and the life course. The sequence involves key social roles that are played by parents, grandparents, and the adolescents within the last six years of secondary school. As applied in this study, life-course theory14 locates all of this within a particular historical time and place, stresses the role of parents and children as agents in working out options in their lives, brings sensitivity to the social timing of lives, and locates families in a matrix of linked relationships. The vitality and quality of this matrix provides the social resources or capital for human development.

This research problem emerged through interaction between the Iowa Youth and Families Project,15 a panel study that was launched in the late 1980s to investigate the continuing socioeconomic effects of the farm crisis on families and children, and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development among Youth in High-Risk Settings.16 Research conducted as part of the Iowa Project has shown that rural families were adversely influenced by the farm crisis and that the emotional and behavioral responses of parents affected the competence and adjustment of their children.17 Lower income and indebtedness increased feelings of economic pressure. Such pressures over time eventually led to depressed feelings and marital negativity. These factors undermined effective parenting and the perceived competence of children.

Moving beyond the legacy of economic hardship, we ask how rural youth manage to succeed in a disadvantaged region through the assistance of family, school, and civic groups. What are the resourceful pathways to greater opportunity? Children of the Great Depression18 led to questions of this kind for Americans who had grown up in the 1930s, and such questions have become more compelling with each new level of inequality in American society. These issues shaped the long-term objectives of the Iowa Youth and Families Project and the research mission of the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

The Iowa Project and the MacArthur Network were joined in 1988 when Elder became a member of the latter and encouraged its efforts to develop a common focus on the pathways that enable youth to surmount their disadvantaged backgrounds. Economic decline in the rural Midwest had become a chronic condition of disadvantage by that time, defining the setting as a high-risk environment. Families with ties to the land, from full-time farming to a farm childhood, theoretically possess social resources that could establish an important bridge to life opportunity for Iowa young people. These resources feature engagement in the community and the shared activities of the generations.

Before turning to the Iowa Project and its life-course approach, however, we describe the contrasting worlds of childhood that are represented by the study region, which is only fifty miles away from Des Moines, the flourishing state capital.

Two Worlds of Childhood: Rural Decline and Urban Prosperity

Rural America presents two faces to the larger society, the appeal of agricultural life, especially for children, and a portrait of chronic, debilitating poverty. Today, children who grow up amidst poverty in rural America are as common as in our inner cities.19 Rural hardship and urban opportunities have fueled rural outmigration, linking the problems and prospects of countryside and metropolis.

The inequality of rural and urban America has widened appreciably over the past decade, generating a contrast that is strikingly apparent as we place the study region in context after the farm crisis and compare it to Des Moines, the largest metropolitan area in Iowa. Des Moines, Iowa’s state capital, has become a diversified center of government, finance, transportation, and high technology. Before turning to this comparison, we note some general trends on rural population decline, urban growth, and the steady expansion of farm size. The study region of eight counties (figure 1.2) lies due north of Des Moines. Webster, Hamilton, Hardin, and Marshall counties make up the lower tier; Humboldt, Wright, Franklin, and Butler comprise the upper tier.

This rich agricultural region, with land values above the state’s average, lost half of its farms between 1950 and 1990, as did Iowa as a whole, and the decline in other parts of the country was comparable. During the same period, farm size nearly doubled for the study region (up to 361 acres, 1992), as it did in the state and nation. The study region’s population declined by 12 percent over this forty-year period, and virtually all of the loss occurred in the farm sector. Two counties lost nearly a third of their mid-century population over this period. At the same time, the state population grew by 6 percent, mainly in rural nonfarm and urban areas, despite a net loss for the 1980s. As might be expected, Des Moines was the principal beneficiary of this growth—an inc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Series Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Part 1. Rural Change and Life Chances

- Part 2. Pathways to Competence

- Part 3. Past, Present, and Future

- Appendixes

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index