- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agrarian Revolt in a Mexican Village

About this book

Agrarian Revolt in a Mexican Village deals with a Taráscan Indian village in southwestern Mexico which, between 1920 and 1926, played a precedent-setting role in agrarian reform. As he describes forty years in the history of this small pueblo, Paul Friedrich raises general questions about local politics and agrarian reform that are basic to our understanding of radical change in peasant societies around the world. Of particular interest is his detailed study of the colorful, violent, and psychologically complex leader, Primo Tapia, whose biography bears on the theoretical issues of the "political middleman" and the relation between individual motivation and socioeconomic change. Friedrich's evidence includes massive interviewing, personal letters, observations as an anthropological participant (e.g., in fiesta ritual), analysis of the politics and other village culture during 1955-56, comparison with other Taráscan villages, historical and prehistoric background materials, and research in legal and government agrarian archives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agrarian Revolt in a Mexican Village by Paul Friedrich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER FIVE

Agrarian Revolt: 1920–1926

Viva, viva, siempre, las ideas de Primo Tapia, Viva, viva, siempre, la Constitucion.

Folk Song of the Naranja Agrarians

INITIAL ORGANIZATION

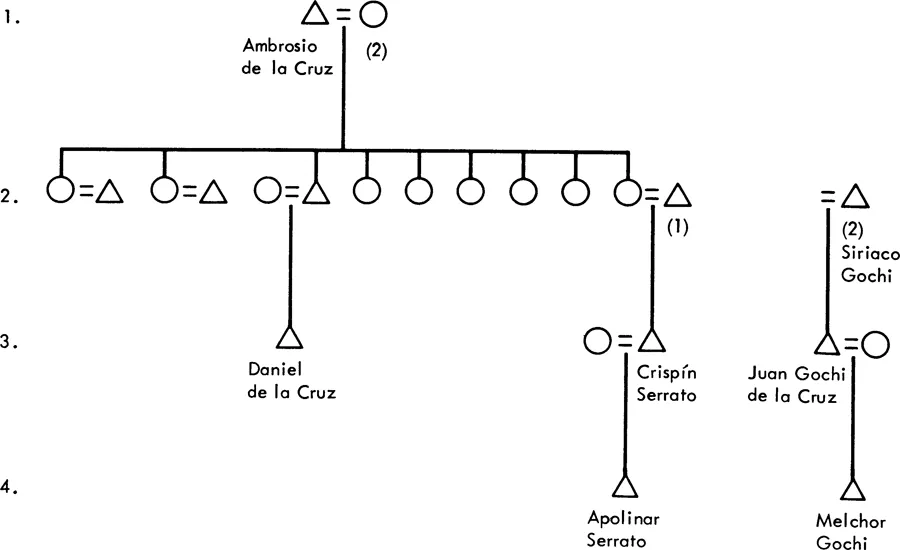

Primo knew that success in the region depended on having a band of loyal relatives and neighbors in one’s native community. Thus, it was essential in his revolutionary design to improve and bring under his control the organization of local partisans created by his uncle. Within a few weeks after returning home late in 1920, he arranged a clandestine meeting in the house of Crispín Serrato, an older man with a reputation for wisdom in debate. Of the ten who attended, about half were sympathetic to Tapia and about half sided with his cousin and immediate predecessor, Juan Gochi de la Cruz, who had led “The Third Agrarian Committee” between 1914–1916 and had assumed command over the local organization after the assassination of Primo’s uncle in 1919. Factions arise in Naranja politics almost as soon as the group approaches a dozen and involves more than one family.

By June 1921, after ten months of discussion and informal campaigning, Juan was elected to represent the pueblo’s agrarian program to higher authorities, while Primo and another first cousin Pedro López received only about 25 votes each. Primo was often impatient with Juan’s legalism; once, for example, he tore up some of Juan’s official correspondence with the exclamation, “What are these things good for? To deceive the people!”

By October, Primo was elected town secretary, replacing a man who had switched his allegiance to the hacienda. By the end of the year, “the poorest were united under Juan Gochi and Primo Tapia.” But because Juan had allegedly fallen sick, it was Primo who signed “the agrarian census,” a list of those willing to petition for land. Through Primo’s leadership potential fission between the Gochis and the Cruzes had been temporarily neutralized with a speed that suggests both the effectiveness of his methods and the way he had managed to fill a vacuum created by the assassination of his uncle. Political action in Naranja involves a delicate balance between the need for a single, effective “representative,” and the tendency of the pueblo to fragment into two rival factions.

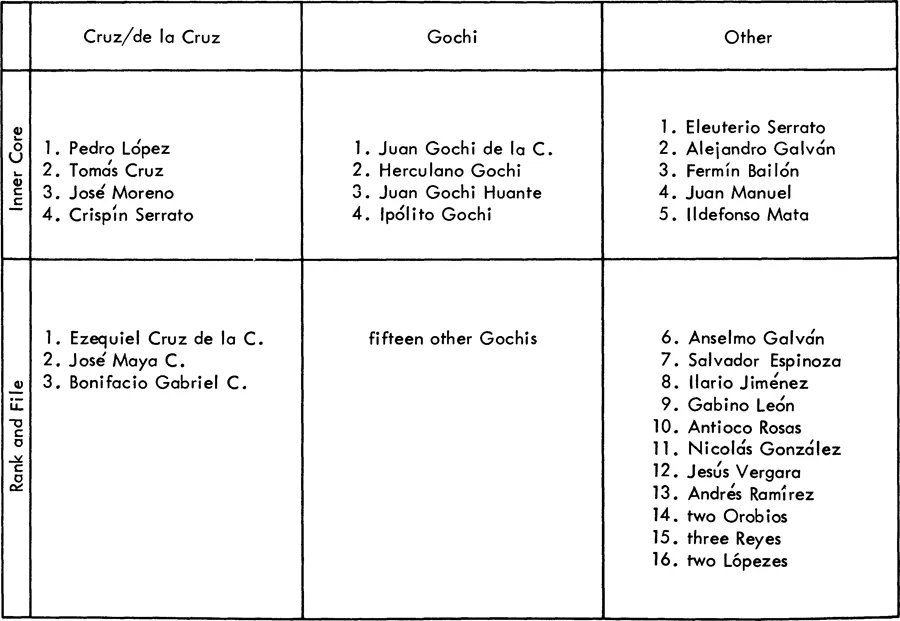

Since many Naranjeños were politically apathetic, the number of one’s followers was hardly more decisive than their personal qualities; the identity and character of Primo’s fighters and lieutenants can still be reconstructed with considerable reliability, despite disagreements today between Gochis and Cruzes. Thumbnail sketches and a simple roll call are given below, partly in justice to the men themselves, partly as a dramatis personae for the history that follows.

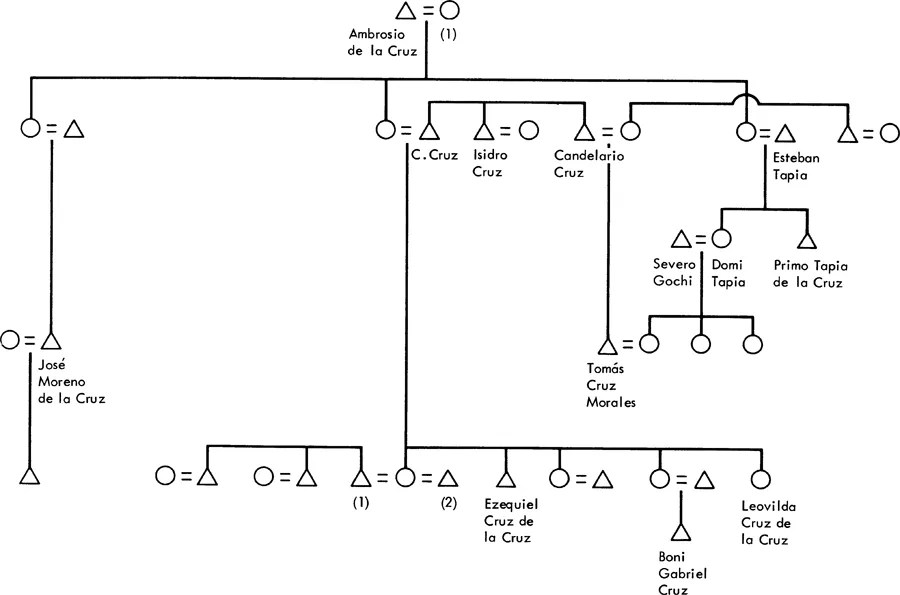

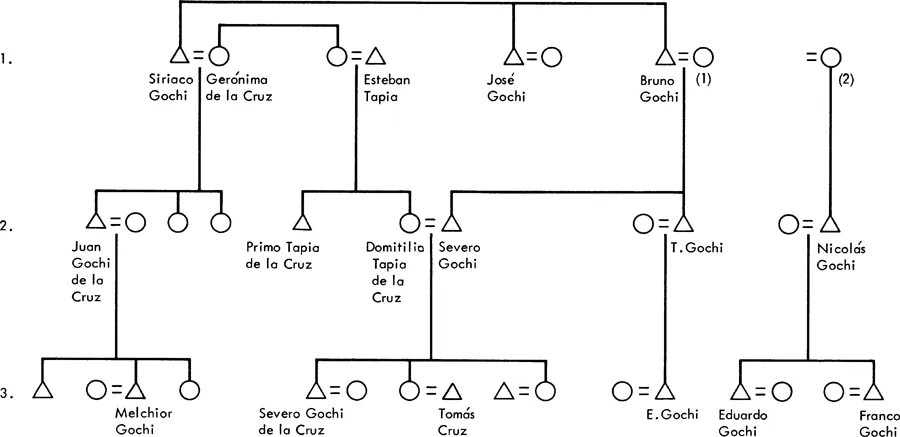

The men were of three kinds. An inner circle numbering about fifteen was led by Tomás Cruz Morales, a thin man, nearly six feet tall, and very intelligent. Tomás was a “distant cousin” of Primo, and married to his niece. He eventually was to lead the pueblo for about one year (1927–1928).1

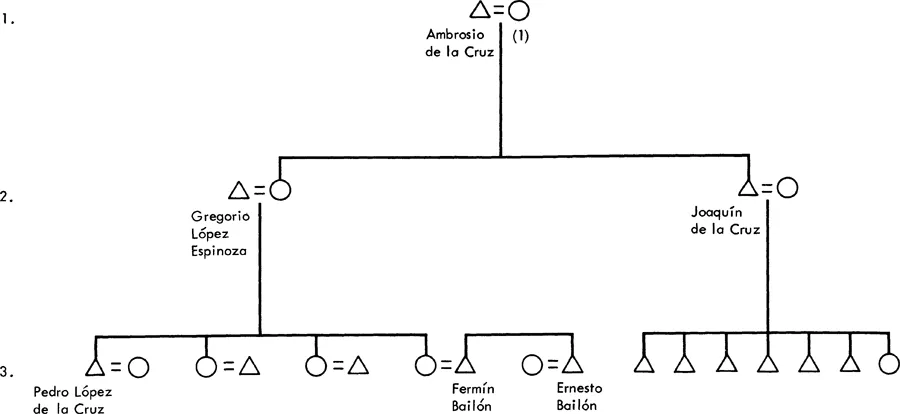

Most important of the five cousins in the next line was the chubby and energetic Pedro López, who stood by Primo during the years of agrarian revolt and who eventually played an important role in state politics during the 1930s. Primo’s intimate friend José Moreno de la Cruz had chummed with him as a boy and, together with Pedro, had helped organize the anarchist strike in Nebraska in 1919. Yet another cousin, Ezequiel Cruz de la Cruz, was forced to flee Naranja late in 1921 after shooting one of Primo’s closest followers in a drunken brawl. The fourth first cousin was Juan Gochi, already depicted above as the outstanding local leader under Primo’s uncle and the main representative of the Gochi political family. Finally, there was Crispin Serrato de la Cruz, who had served on “The Third Agrarian Committee” (1914–1916); he was the elder statesman whose house served as a meeting

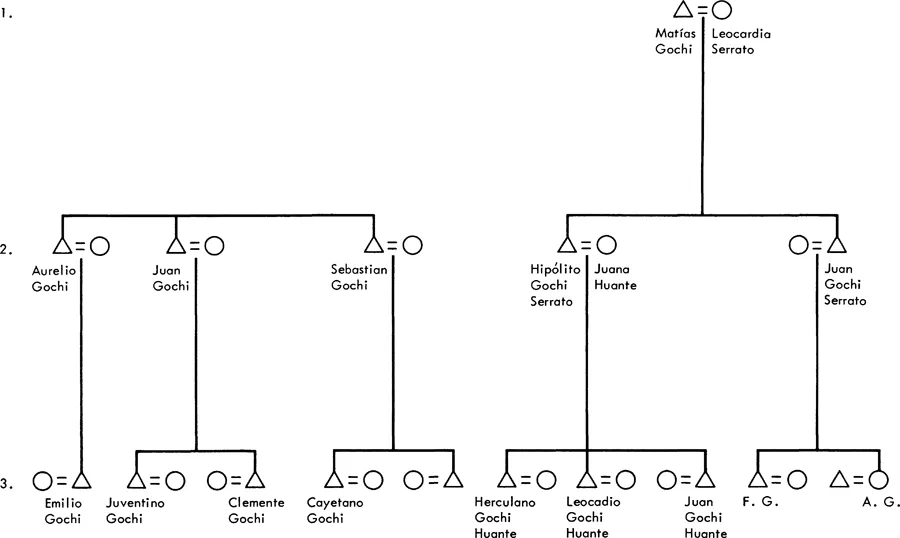

Genealogical Stemma for the “Cruz—de la Cruz” Group (1)

Genealogical Stemma for the “Cruz—de la Cruz” Group (2)

Cruz and Gochi

The Gochis (1)

The Gochis (2)

Primo’s Men

place.2 Primo’s mother and the mothers of these five cousins were all sisters to Joaquín de la Cruz, the village’s first agrarian hero.

Though not part of the inner core, two distant nephews to Primo and first nephews to Tomás were listed in the first agrarian census and emerged as versatile and dedicated partisans toward the end of the agrarian revolt. One of them was José Maya Cruz, later to become the most dangerous “fighter” in Naranja history. The other was the man who murdered Eleuterio Serrato in 1924. Thus, although he lacked brothers, fraternal nephews, and a father, Primo received critical support from several tiers of aunts, cousins, and nephews, all linked through his mother and sister. Matrilineal ties, especially when distant, do not imply automatic loyalty in Naranja politics, but here they provided a set of options to Primo’s kinsmen that could interlock with more decisive, economic forces and the compelling power of his own leadership.3

Primo’s inner core also included a number of lesser figures. Juan Manuel was notorious for his expertise with both knife and pistol. Another was Fermín Bailón, “a simple peasant, loyal to the principles of agrarianism” and subsequently married to a sister of Pedro López; marriage ties often result from politically motivated friendships.4 The two most distinguished gunmen were Alejandro Galván and Eleuterio Serrato, the latter famed for his rabid courage and, at the time of his death in 1924, perhaps second in authority to Primo Tapia himself. A personal “friend of confidence” (amigo de confianza) was Ildefonso Mata, Primo’s companion on several wild sprees in the sierra, and the sole agrarian in the otherwise anti-agrarian and mestizo Mata family.5 The five followers just named were probably attracted by the leadership of Primo Tapia, by the idea of land reform, and by the general atmosphere of elan.

By 1922, the inner group under Primo was made up basically of Cruzes and of Gochis. A half dozen members of the Gochi political family or name group had become leaders under Primo more because of shared interests rather than affection or kinship. Herculano Gochi, perhaps foremost among them, had graduated from a secondary school in Pátzcuaro and partly finished a legal education before serving in the cavalry during the Revolution; he was to introduce Tapia to Múgica and to remain his right-hand man until 1924; one has little difficulty in visualizing the agrarista of 1920 after seeing the stocky, nut-brown, volatile man of 1956. He had two brothers, Leocadio and Juan. Leocadio is still remembered as “tough” (duro), and figured prominently during the factionalism of the late 1920s and early 1930s. Juan, a man of considerable political and military ability, eventually became head of all the militia in the Zacapu valley, once leading an army of 300 agrarians into the tierra caliente during the religious wars of 1928. The formidable block of these three brothers was completed by their father Ipólito, who had served on the “Third Agrarian Committee” (1914–1916). The gap between the Gochis and the Cruzes was bridged by the marriage of Ciriaco Gochi to one of the daughters of Ambrosio de la Cruz; their son Juan Gochi de la Cruz has been discussed, and his son was to emerge as an aggressive fighter for the agrarian cause. Primo’s sister was married to a Gochi. These affinal alliances probably helped hold the two lines together. But on the whole, the Cruzes, so-called, were but weakly bound to the forty-odd men who bore the name Gochi as patronymic or matronymic.

In Naranja, politics is to a significant degree thought of in terms of kinship: the support of a group of kinsmen is indispensable to a leader, and hostile groups are sometimes largely expelled or killed off. Aside from the blocks of immediate relatives and various dyadic relationships, as between uncle and nephew, the Naranjeño conceives of politics in terms of the somewhat more loosely structured “political families,” referred to in the first chapter, and illustrated by the Cruzes; as noted, such political families may be phrased in terms of ties that are almost entirely matrilineal. Usually, however, they are expressed in terms of a last name shared as patronymic or matronymic. Since the individual receives his patronymic from his father and his matronymic through his mother from his mother’s father, the political family consists largely of people related by patrilineal or marital allianceties. But some persons are always linked through marriage alone, especially the marriage of onself, one’s children, or one’s sibling; the latter is illustrated by the husbands of Pedro López’s two sisters.

Political families tend to be genealogically shallow, in that relationships are not calculated to great distances; yet they may be terminologically comprehensive, in that many persons are aggregated under a shared surname. And since genealogical ties beyond second cousin are not accurately reckoned or consistently remembered, there may be some persons who claim a kinship which is not even a true name relationship, as between the supposed “cousins” Tomás Cruz and José Moreno de la Cruz. Such a system allows considerable freedom of alignment to politically or economically motivated individuals; thus, Primo and the Cruz/de la Cruz faction were devoutly supported by Primo’s distant “nephew” José Maya Cruz but opposed by a man who was genealogically central, Daniel de la Cruz, a first cousin of Primo Tapia. Even the idea of “name” is fluid; all persons agree that Cruz and de la Cruz are different forms symbolizing different lines of descent; but in their political idiom, which is used also in the following analysis, all Cruzes and de la Cruzes are lumped together as one “family,” the Cruzes. With these patterns in mind, let us turn to the next layer of political organization.

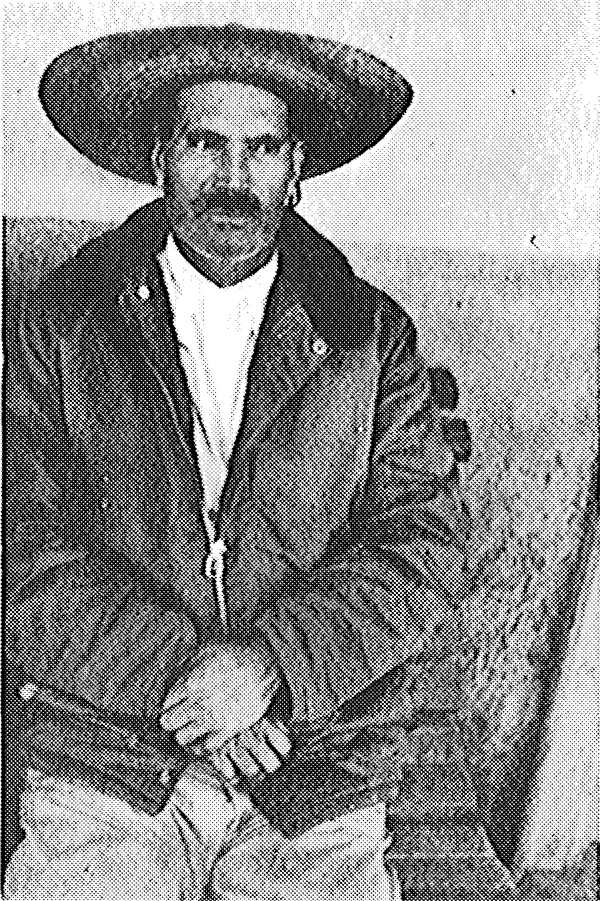

The outer shell of Primo’s group comprised a large number of agrarians, recalled by witnesses with a remarkable degree of consensus. In this rank and file were Anselmo Galván (brother to the fighter Alejandro), Salvador and Raymundo Espinoza, Ilario (and probably Antonio) Jiménez, Gabino León (the husband of another of Pedro López’s sisters), Antioco Rosas (father to a young gunman of 1956), the three Reyes brothers, Eduardo Cipriano, two López brothers (related to Pedro), Jesús Vergara, Andres Ramirez (“the only rich agrarian”), two more brothers, Federico and Francisco Orobio, and, finally, Pedro Sarco and Nicolás (“Bones”) Gonzalez.6 Though this score of youthful men ranged between their late teens and late thirties when Primo returned, only the last three were still alive by 1956. No one in the outer shell was a close relative of Primo, but many were bound to each other by kinship, the compadrazgo, or intimate friendship.

Nicolás González (1956)

A Nephew of Primo Tapia (1956)

What common denominators characterized the members of “the powerful and fighting agrarian organization of Naranja” (Anguiano Equihua 1951:31)? First, many had known Primo as a boy and as a young man and were ready to accept him as “one of us” when he explained his program of reform.

The second common denominator is that most of the men came from impoverished families and stood to gain economically. The twenty-odd younger men in the outer circle were almost all landless, the children of Indians who had been hired as peons to work for the local landlords or on the great sugar plantations in the south. One reason practically all the Gochis were musicians is that they had little or no land. Of the inner core, only Pedro López appears to have been prosperous, although several others were reasonably well off. Agrarian revolt in Naranja was partly caused by a conflict among many de la Cruzes between harsh realities and political expectations; their inadequate lands and their subordination to the new mestizo caciques was simply incompatible with their status as grandsons of the communal leader, Ambrosio de la Cruz.

The third common denominator of Primo’s men was cultural. Except for the comparatively educated Pedro López and Herculano Gochi, most were illiterate or barely literate. And all but three were thoroughly Tarascan in culture.7 In the fourth place, about half had participated at some time in the Mexican Revolution and had thus acquired skill in guerrilla and small-scale infantry fighting; some, such as Ezequiel and Tomás Cruz, had fought for several years. Primo’s men did not differ in any biological, genetic sense from the Tarascans of today, but a peculiar concatenation of economic, political, and ethnic causes had produced a tough, highly motivated political group.

Beyond the inner core and outer shell Primo enjoyed the lukewarm or potential allegiance of about fifty other men, including many unnamed Gochis, who would swing to his side as the struggle for land promised success. Primo’s group constituted a minority, as do most radical factions in Mexico, but a large minority that was relatively organized and that came to be increasingly articulate in its ideology.

During 1921, Primo institutionalized his core as the innocuous-sounding “Committee for Material Improvements,” which proposed and carried through a drastic change of wide popular appeal; for purposes of hygiene the graveyard was moved from its position before the church and relocated about a half a mile away to the southeast, while the central area was converted into a plaza and planted with grass and flowers. Primo argued in terms of the prevailing humoral pathology that corpses interred in the midst of the community would wreak noxious influences. Naranjeños still express resentment at the “unsanitary,” almost ghoulish exploitation of the plaza area for a graveyard. But Primo’s tactic had obvious anti-clerical and anti-medieval connotations; in setting the stage for agrarian revolt one should remove such grim symbolic deterrents as cemetery crosses.

A longer-range problem was the increasing impoverishment of Naranja and of the agrarian Naranjeños in particular (as is detailed in Appendix B). Not only was there less work in the southern plantations, but the local hacendados systematically refused to employ anyone associated with land reform—“the latifundians having broken all relations with the petitioning proletarians” (letter from Tapia to the Local Agrarian Commission, October 13, 1922). By 1921 over half of Naranja was in fact proletarian in the technical sense of subsisting from wage labor obtained through contract. Discrimination against the landless peons caused hardship, as indicated in another letter from Tapia, dated July 5, 1922:

The indigenes with whom I am concerned have been suffering from an absolute boycott on the part of the hacendados . . . constituting an important factor in the disequilibrium among the persons forming the collectivity, and the cause of numerous disturbances among the proletariat.

On the other hand, the destitution of his villages gave Primo a strong argument before the agrarian officials. As he put it:

It is notoriously illogical to pretend that, on the basis of public need (utilidad), one can continue to encourage the monopolization of wealth by a few persons who cannot realize that the emancipation of the rural slave in our country is the maximum public need, the supreme national necessity.

As the struggle progressed, financial need conjoined with Primo’s own astuteness to generate a now famous hoax. The local agrarians had to be armed and expensive trips often had to be undertaken to Morelia and Mexico City. Early in 1922, Primo received a secret message from the Spaniards of Cantabria.8 The same night he rode across the black soil of their plantation for a conference. He was offered a large bribe, allegedly of 300, 1,000, or 5,000 pesos (depending on the informant), and told, “If you don’t withdraw, we will run you out.” The following night Primo collected, then immediately left for Morelia where he used the money to support himself and to pay the legal fees for the provisional grant of the ejidos. The grant actually materialized later the same year under the new provisions of the Agrarian Regulatory Law described below. Aside from its anecdotal value, this story came to symbolize to the Zacapu valley agrarians Primo’s ingenuity and dedication in solving their problems.

Another immediate problem confronting Primo was the paradoxical refusal of most Naranjeños to participate actively in any land claims; “The ejido was for their own benefit, but many didn’t want it.” They did not want the land because of a combination of influences: the clergy was preaching against the reform, some of the peasants were being intimidated by the mestizo caciques, and others were employed by the landlords or indebted to them. In particular, the clergy, caciques, and landlords were threatening Primo’s efforts to demonstrate a widespread and genuine need for reform in order to obtain the largest possible amount of land throu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Chronology of Important Events

- Preface, 1977

- Preface

- One. Prologue

- Two. The Cultural Background: Naranja Circa 1885

- Three. Economic and Social Change 1885–1920

- Four. An Indigenous Revolutionary: Primo Tapia

- Five. Agrarian Revolt: 1920–1926

- Six. Epilogue

- Seven. Postscript: The Causes of Local Agrarian Revolt in Naranja

- Appendix A. The Tarascan Language

- Appendix B. Economic Statistics for the Ejido

- Appendix C. Diet

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Supplementary Bibliography