eBook - ePub

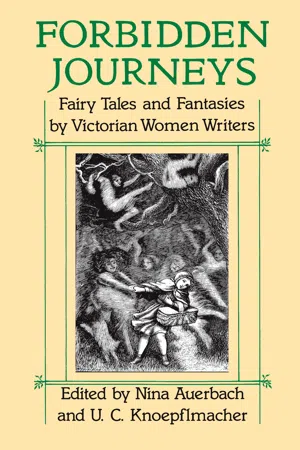

Forbidden Journeys

Fairy Tales and Fantasies by Victorian Women Writers

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forbidden Journeys

Fairy Tales and Fantasies by Victorian Women Writers

About this book

As these eleven dark and wild stories demonstrate, fairy tales by Victorian women constitute a distinct literary tradition, one startlingly subversive of the society that fostered it. From Anne Thackeray Ritchie's adaptations of "The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood" to Christina Rossetti's unsettling antifantasies in Speaking Likenesses, these are breathtaking acts of imaginative freedom, by turns amusing, charming, and disturbing. Besides their social and historical implications, they are extraordinary stories, full of strange delights for readers of any age.

"Forbidden Journeys is not only a darkly entertaining book to read for the fantasies and anti-fantasies told, but also is a significant contribution to nineteenth-century cultural history, and especially feminist studies."—United Press International

"A service to feminists, to Victorian Studies, to children's literature and to children."—Beverly Lyon Clark, Women's Review of Books

"These are stories to laugh over, cheer at, celebrate, and wince at. . . . Forbidden Journeys is a welcome reminder that rebellion was still possible, and the editors' intelligent and fascinating commentary reveals ways in which these stories defied the Victorian patriarchy."—Allyson F. McGill, Belles Lettres

"Forbidden Journeys is not only a darkly entertaining book to read for the fantasies and anti-fantasies told, but also is a significant contribution to nineteenth-century cultural history, and especially feminist studies."—United Press International

"A service to feminists, to Victorian Studies, to children's literature and to children."—Beverly Lyon Clark, Women's Review of Books

"These are stories to laugh over, cheer at, celebrate, and wince at. . . . Forbidden Journeys is a welcome reminder that rebellion was still possible, and the editors' intelligent and fascinating commentary reveals ways in which these stories defied the Victorian patriarchy."—Allyson F. McGill, Belles Lettres

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forbidden Journeys by Nina Auerbach, U. C. Knoepflmacher, Nina Auerbach,U. C. Knoepflmacher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & English Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Chicago PressYear

2014Print ISBN

9780226032047, 9780226032030eBook ISBN

9780226230528Part One

REFASHIONING FAIRY TALES

Women writers of the Victorian era regarded the fairy tale as a dormant literature of their own. When Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre hears hoofbeats approaching her in the dark, ice-covered Hay Lane, “memories of nursery stories” immediately flood her mind, especially the recollection of “a North-of-England” monster capable of assuming several bestial forms. But the beastly apparition Jane expects turns out to be Rochester, the “master” whom she promptly causes to fall off his horse and who will eventually become her thrall. Rochester himself soon shows his own conversance with, and respect for, powers he associates with the magical women of traditional fairy tales. “When you came on me in Hay Lane last night,” he tells Jane, “I thought unaccountably of fairy tales, and had half a mind to demand whether you had bewitched my horse. I am not sure yet. Who are your parents?” When Jane replies that she is parentless, Rochester endows her with a supernatural ancestry. Surely, he insists, she must have been “waiting for [her] people,” the fairies who hold their revels in the moonlight: “Did I break one of your rings, that you spread the damned ice on the causeway?” (chapter 13).

Here and elsewhere in Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë takes even more seriously than her two characters do the potency of the female fairy-tale tradition to which she has them refer. Karen E. Rowe, who has so ably written on that tradition, was the first to show how fully saturated Jane Eyre is with patterns drawn from major folktales such as “Cinderella,” “Sleeping Beauty,” “Blue Beard,” and, as a prime analogue for Jane’s developing relationship with the homely Rochester, from “Beauty and the Beast,” the 1756 Kunstmärchen (or literary fairy tale) adapted and popularized by Madame Le Prince de Beaumont.

Proscribed for its paganism by successive religious authorities, the orally transmitted fairy tale lingered in the popular imagination just as fays and gnomes had themselves presumably survived in the less populated regions of the British Isles. In literature written for children, however, such fantastic narratives had been forced to vie, for an entire century, with the moral fables preferred by even such eminent women educators as Maria Edgeworth, whose fine stories for children display her wariness of a demonic imagination. Even though French precieuses such as d’Aulnoy, L’Heritier, de Villeneuve and, eventually, a writer like Beaumont (whose 1756 Magasin des Enfans was actually printed in London) had penned fairy tales of their own, the earlier oral tradition of the contes de vieilles, or old wives’ tales, continued to be regarded as crude and subliterary. Not until the Romantic fascination with primitivism, childhood, and peasant folklore redirected collectors like the Grimms to female informants such as Dorothea Viehmann, did the genre’s rich mythical veins again become accessible, and its female origins become fully apparent to a dominant literary culture.

Victorian male writers promptly appropriated these materials. As much attracted to the imaginative wealth of this storehouse as to its female sources, they soon assimilated for their own creative purposes the folktales—English, Scottish, Irish, and Scandinavian—which antiquarians, mythographers, and folklorists now were assiduously collecting in emulation of the Brothers Grimm. Victorian women writers, however, still expected by their culture to adhere to and propagate the realism of everyday, were at a decided disadvantage. Unwilling to be stereotyped as fantasists, eager to be valued for their social realism, they found themselves prevented from overtly acknowledging the importance for their own creative efforts of the fantasy lore bequeathed to them by their anonymous foremothers. Whereas male writers such as Tennyson, Dickens, or Ruskin could openly enlist fairy tale materials they found in the collections by Thomas Keightley or the Grimms or even in the treasure trove of The Arabian Nights, that product of another female story-spinner’s craft, their female counterparts had to proceed far more covertly. Jane Eyre disparages her belief in the North-of-England “Gytrash” as childish “rubbish,” even though she adds that her credulity actually was strengthened during the period of her “maturing youth.” To mine the mythic richness of the fairy tales so important to Brontë’s own imaginative development thus required the adoption of authorial strategies of indirection and disguise. Such tactics prevail even in the texts we present in the second, third, and fourth parts of this anthology, where the fantastic is far more directly embraced than in Jane Eyre.

By recasting known folktales, as the three authors introduced in this first part so skillfully do, Victorian women writers could tap more openly the mythic female sources Brontë must half deny. Like Brontë, the three novelists we have chosen—Ritchie, Molesworth, and Ewing—possess a powerful imagination of their own. Yet by posing as mere translators or adapters, they can activate the traditional materials they appropriate without having to risk being accused of indulging in child-like fantasies. Indeed, in the first two selections, “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood” and “Beauty and the Beast,” which open Anne Thackeray Ritchie’s Fairy Tales for Grown Folks, childishness is kept at bay by the invitation to reinspect from an ironic adult perspective the archetypal relevance of tales removed from the confines of the nursery. A similar sophistication deepens Maria Louisa Molesworth’s “The Brown Bull of Norrowa” and Juliana Horatia Ewing’s “Amelia and the Dwarfs.” These enlargements of a Scottish fairy tale and an Irish fairy tale are addressed to the child reader as much as to the adult. Although both readers can equally appreciate the resourcefulness of each tale’s young female protagonist, only the grown-up can also grasp the cultural poignancy of parables as concerned with female empowerment as Jane Eyre.

Significantly enough, old women—some of them superannuated—play a major role in each of these selections. Ritchie’s narrator is gradually revealed to be an aged spinster called Miss Williamson, a name that befits the real-life daughter whom William (Thackeray) had brought up as his literary son. (For her Blackstick Papers, a collection of essays, Ritchie even chose to impersonate the wise centenarian Fairy Blackstick, who dominates in the fairy tale Thackeray had originally written for her sister and herself, The Rose and the Ring.) Miss Williamson lives with the widow known as “H.,” and with her friend’s grandchildren, in a placid community of women that seems to be patterned after Gaskell’s Cranford. The quiescent, ordinary, drab lives she observes in the minutely detailed fashion expected of Victorian realists introduce us to other old ladies: the appropriately named Mrs. Dormer, for instance, “long past eighty now,” who seems to have been nodding for years before she notices that her great-niece and godchild is no longer eighteen but twenty-five. This dozing benefactress must be roused in order to enact the traditional role of fairy godmother in “The Sleeping Beauty of the Woods.” Her “arts” have become rusty after such long disuse. Nonetheless, as the artlessly artful narrator herself makes us see, fairy-tale patterns still obtain in everyday life. Whereas the goody-goody children of didactic children’s fiction have long since expired, fairy-tale creatures like Mrs. Dormer and Miss Williamson still thrive, “everywhere and every day.” Their immortality is explained by H.: “All these histories are the histories of human nature, which does not seem to change very much in a thousand years or so, and we don’t get tired of the fairies because they are so true to it.”

Although Ritchie’s stories end with marriage, it is significant that her narrator should be an old single woman. Originally used to denote the occupation of those women capable of spinning wool as well as stories, the term “spinster” did not become attached to unmarried women until the seventeenth century. The title page to Perrault’s 1695 Contes de Ma Mere Loye offered an etching of the wool-spinning crone, seated with children and adults before an open hearth, that became an icon for all future verbal and pictorial representations of the figure variously known as Mother Goose or Dame Bunch. Ritchie’s Miss Williamson, though a genteel Victorian lady, is this figure’s latter-day incarnation. Her aged youthfulness makes her perfectly suited as a purveyor of the old but ever-fresh tales she merely needs to replant.

Comfortably situated with her female friend H. on “either side of the warm hearth,” Miss Williamson does not have to rake up coals for any frozen Rochester. The two women spend the winter evenings of their lives “without fear of fiery dwarfs skipping out of the ashes.” In Villette, the novel that revises Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë made sure that her new heroine would not be compelled to wed the ugly male Beast who desires a mate. Though Miss Williamson is most sympathetic to the young men to whom she assigns the roles of Prince and Beast in her two narratives, her own sexual segregation (like that of unmarried writers such as Rossetti and Ingelow) allows her to treat marriage plots with wry detachment.

Old women also figure prominently in the selections from Molesworth and Ewing. The white-haired woman, “spinning busily,” encountered in a dream by the children in Molesworth’s The Tapestry Room, is of an undetermined age, as the narrator makes sure to stress: “No doubt she was old, as we count old, but, except, for her hair, she did not look so.” This strange white lady, who proceeds to tell the story of the Princess and the Brown Bull, acts as an intermediary between the children’s old nurse Marcelline and the two old women within the tale (one of whom seems to be the same fairy who gave the princess her magical balls). Molesworth relishes these refractions and blendings of a figure who also stands for her own authorial self. Marcelline, the dream-narrator, the “kind old woman” who shelters the princess, are all purveyors of an oft-told tale honed and embellished by a succession of female spinners.

Ewing’s “Amelia and the Dwarfs” calls attention even more prominently to its venerable ancestry in female folklore. The opening sentence invites us to go back five generations to the grandmother of “my godmother’s grandmother.” Ewing’s acknowledged dependence on a distant old wife’s tale makes her narrator assume the role of transmitter. And it is true that this deliciously comic masterpiece faithfully follows the contours of the tale of “Wee Meg Barnilegs,” the folktale still told to Ruth Sawyer in the 1890s by her Irish nurse and reprinted in Sawyer’s The Way of the Storyteller. But Ewing does much more than reset a peasant tale in the genteel Victorian society she so relentlessly satirizes. Among her many improvisations is the addition of the “old woman” Amelia encounters in the underground into which she has been thrust by the sadistic dwarfs. Like the Apple Woman in Ingelow’s Mopsa the Fairy (reprinted in part 3), this fellow captive is “a real woman, not a fairy.” She has lost all sense of time in her long period of servitude. Though she prefers the timelessness of surroundings unmarked by days and nights, and hence has decided to remain in the penumbra (and anonymity) of her underground existence, she nonetheless instructs Amelia how to escape through the sexual wiles her clever pupil promptly exploits. Whereas, in the Irish folktale, the male dwarfs bring about Wee Meg’s reform, in Ewing’s version it is the dwarfs’ slave who remains Amelia’s prime tutor.

In all of these tales, then, older women come to the aid of the young. Ritchie’s Miss Williamson and Mrs. Dormer act as marriage brokers for the clumsy and the naive; Molesworth’s enchantresses provide shelter and magical tools; Ewing’s slave woman discharges the role that neither Amelia’s fumbling mother nor her impotent nurse were able to perform in a stratified and genteel Victorian order. But if these figures are invested with powers traditionally assigned to fairy godmothers, young women themselves are credited with an ingenuity and resilience that restores some of the power they possessed in a matriarchal culture.

Dull Cecilia Lulworth, to be sure, in Ritchie’s “The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” is the exception that proves the rule. Lacking all wit, she insists on discoursing about slugs at the dinner table; lacking any taste or even an awareness of her own attractiveness, she chooses “a sickly green dress,” hideously trimmed, as her “dinner-costume.” In her portrait of sluggish Cecilia, Ritchie mocks the female passivity that so attracted Victorian males to the sleeping beauties they tried to awaken with a kiss. Cecilia’s tears exasperate her outspoken godmother, who declares that the “girl is a greater idiot than I took her for.” But they utterly disarm young Frank Lulworth, the “young prince” touched by her “simplicity and beauty.” As Ritchie implies, simplicity and beauty appear to be largely in the eyes of prospective princes. Frank is as charmed by Cecilia’s “silly” crying as George Eliot’s Lydgate is moved by the teardrops shed by his imaginary water nixie in Middlemarch, the novel which Virginia Woolf described as written for truly “grown-up people” in an essay in which she also cites her mentor and step-aunt, Lady Ritchie. Ritchie’s tale for “grown folks,” however, permits “fairy transformations” that would be impossible in Middlemarch.

Ritchie’s revision of “Beauty and the Beast” features a far more energetic heroine than stolid Cecilia. It is true that the bestial male whom Belle Barley is compelled to serve is neither as frightening as the monster who tries to detain Beauty in his mansion in the original tale nor as wonderfully duplicitous as the bigamist who conceals the existence of his vampiric, attic wife in order to keep Jane Eyre at Thornfield. Brontë’s Rochester must be demasculinized as much as the senseless and broken Beast whom Beauty finds near death in the original fairy tale. But in Ritchie’s revision, masculinity is never a threat. Guy Griffiths, the Beast to Belle’s Beauty, may be “rough-looking” and clumsy, especially when he smashes crockery or wields a “huge seal, all over bears and griffins.” But his empathy and susceptibility to female guidance are apparent from the story’s outset.

Indeed, Guy’s resemblance to his presumed foil, Belle’s impotent father, is much more marked than in the original. Both men are excessively prone to self-pity and self-derogation. Both are decidedly subservient to stronger females. Guy transfers this submissiveness from his unloving mother to Miss Williamson and the widow H., who become the story’s good fairies. Belinda’s father, on the other hand, allows himself to be so utterly dominated by her mean-spirited older sisters that he cannot even value the sacrifices he exacts from his sanest and most loving child. By dwelling so extensively on this patriarch’s pathology, and by removing from her cast of characters the three loving brothers Beauty possessed in the original tale–soldiers willing to fight for her against the all-powerful Beast—Ritchie further accentuates the passivity of the male figures. It is the women who decide the story’s outcome.

Ritchie invites us to regard Belle’s preference for her shaggy jailer to her feckless father as a sign of her maturation. Guy does not undergo anything resembling the miraculous transformation which, in the original tale, changes an agonized monster “into one of the loveliest princes that ever eye beheld.” But Guy’s agonies were never as profound as either Beast’s or Rochester’s. Though found “lying on the grass” by Belle, he is hardly near death. He has merely fallen asleep and, in a reversal of “Sleeping Beauty,” this ugly male can now be awakened by a female kiss. Like Belle’s merchant father, he is still prone to protest that he does not deserve such abundant recompense. But under her tutelage, he will soon be cured of both his propensity for self-belittlement and his tendency to treat romance as some sort of barter.

If Ritchie’s story ends on a note more prosaic than passionate, Maria Louisa Molesworth’s “The Brown Bull of Norrowa” revises “Beauty and the Beast” to more effervescent effect. Molesworth’s princess moves deftly through a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One. Refashioning Fairy Tales

- Part Two. Subversions

- Part Three. A Fantasy Novel

- Part Four. A Trio of Antifantasies

- Notes

- Biographical Sketches

- Further Readings