- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

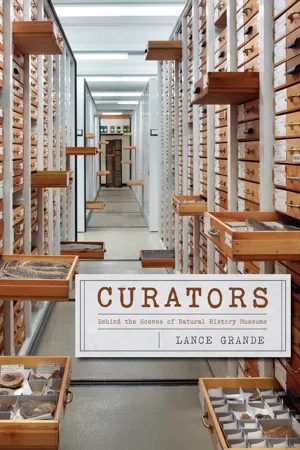

Over the centuries, natural history museums have evolved from being little more than musty repositories of stuffed animals and pinned bugs, to being crucial generators of new scientific knowledge. They have also become vibrant educational centers, full of engaging exhibits that share those discoveries with students and an enthusiastic general public.

At the heart of it all from the very start have been curators. Yet after three decades as a natural history curator, Lance Grande found that he still had to explain to people what he does. This book is the answer—and, oh, what an answer it is: lively, exciting, up-to-date, it offers a portrait of curators and their research like none we've seen, one that conveys the intellectual excitement and the educational and social value of curation. Grande uses the personal story of his own career—most of it spent at Chicago's storied Field Museum—to structure his account as he explores the value of research and collections, the importance of public engagement, changing ecological and ethical considerations, and the impact of rapidly improving technology. Throughout, we are guided by Grande's keen sense of mission, of a job where the why is always as important as the what.

This beautifully written and richly illustrated book is a clear-eyed but loving account of natural history museums, their curators, and their ever-expanding roles in the twenty-first century.

At the heart of it all from the very start have been curators. Yet after three decades as a natural history curator, Lance Grande found that he still had to explain to people what he does. This book is the answer—and, oh, what an answer it is: lively, exciting, up-to-date, it offers a portrait of curators and their research like none we've seen, one that conveys the intellectual excitement and the educational and social value of curation. Grande uses the personal story of his own career—most of it spent at Chicago's storied Field Museum—to structure his account as he explores the value of research and collections, the importance of public engagement, changing ecological and ethical considerations, and the impact of rapidly improving technology. Throughout, we are guided by Grande's keen sense of mission, of a job where the why is always as important as the what.

This beautifully written and richly illustrated book is a clear-eyed but loving account of natural history museums, their curators, and their ever-expanding roles in the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Curators by Lance Grande in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science & Technology Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Moving toward the Life of a Curator

My thirty-three years as a curator have been filled with exotic adventures, scientific discoveries, and inspiring individuals. A series of chance circumstances and personally influential people set me on track toward a career that has been incredibly rewarding. None of this would have happened if it were not for a captivating gift from an old friend, a compelling university professor in Minnesota, and a few influential curators in London and New York who took an early interest in me.

I grew up in a blue-collar suburb of Minneapolis called Richfield. I lived with my mother, father, four sisters, and a dog—all in a small three-bedroom house with a single bathroom and no basement. I think that is where my competitive spirit first developed, whether competing for time in the bathroom, living space, or prime seating at the dinner table. They were somewhat Spartan living accommodations, but ours was a stable nuclear family with an emotionally supportive environment. My parents had no particular interest in science, but they had no objections to it either. Their support came in the form of encouraging me to follow my heart and embrace the journey. I developed early interests in the natural world because it was an unlimited source of hobbies that I could pursue within my family’s limited budget. Through grade school and high school, I collected rocks and minerals from a local gravel pit, raised small freshwater fishes and crawdads from a nearby pond, and collected small fossils from the crushed limestone that paved my parents’ driveway. I found great beauty and peace in my personal study of nature, and it kept my adolescent mind occupied.

After graduating high school in 1969, I moved into an apartment to set out on my own. I took on a series of part-time jobs and began taking college classes in search of an occupation that might interest me. My higher education in Minnesota started at Normandale Junior College and later moved to the University of Minnesota. Working my way through college with a series of low-paying jobs in the service industry gave me a respect for the time and resources I spent on higher education. At one time or another, I was a popcorn vendor for a baseball stadium, a busboy for a German restaurant, a cook for an Arby’s fast food restaurant, and a weekend drummer/singer for a small-time rock band that played at high school dances and an occasional club. In the early 1970s, I was also a medic in the U.S. Army. Last but not least, there was a year that I spent working in the complaint department of a Montgomery Ward store. Collectively, it was a grab bag of subsistence-level employment to pay for food, rent, and college tuition. The jobs were all character builders of the highest degree and motivators for me to find something better.

By the fall of 1973, I was a junior at the University of Minnesota working toward a business degree. At that point I thought I had figured out what I needed to do with my life; I would either find a job in the retail business like my father or be a teacher like my uncle. Such were the pragmatic goals that had been instilled in me by the working-class environment I had grown up in. The university classes in business were perfectly manageable, but they were not especially engaging to me. I seemed to be plodding along toward an inevitable conclusion.

Then one day in August 1974, something happened that began to change all of that. My friend Hans Radke returned from a vacation in southwestern Wyoming with a souvenir for me. It was a beautifully preserved 52-million-year-old fossil fish in limestone from the Green River Formation. It immediately rekindled my long-harbored interest in natural history. The specimen was so well preserved that it required little imagination to envision it as a living creature, and its unimaginably ancient age further fascinated me. I was enthralled! I couldn’t seem to take my mind off of it. So the next day I took my small treasure to a professor of paleontology at the university, Dr. Robert E. Sloan.

Professor Sloan’s office was in Pillsbury Hall, a monumental structure made of massive red sandstone blocks that was built in 1887. It was the second oldest building of the entire Twin Cities campus and home to the university’s Geology Department. When I arrived at his office, I knocked on the heavily painted panel door and heard a cheerful “Come in.” I opened it, peered down a long, dimly lit aisle, and saw him sitting at the far end of the room, sunk into a large padded chair facing me. The office was dusty and cluttered with great piles of books and papers on the floor and tables. I approached him, introduced myself, and handed him my fossil, asking, “Would you please identify this for me?” He took it, stared at it thoughtfully for a moment, and scratched his head. Then he looked at me, smiled, and said, “No. But if you take my course in vertebrate paleontology, you will be able to identify it yourself!” What could I say to that? I signed up a few weeks later.

Professor Sloan was an extraordinary teacher. He was highly animated, waving his arms about when he spoke. He never used notes and clearly loved what he was doing. His specialty was fossil mammals, but he was a storehouse of knowledge about all types of fossils, and he would constantly interject amusing anecdotes into his lectures. I found paleontology, as well as his high-spirited teaching style, to be captivating. I was so taken with it that by the time the course was over, I had decided to change my major from business and economics to geology and zoology. And as promised by Professor Sloan, I was able to identify the fossil fish from my friend Hans. It turned out to be Knightia eocaena, an extinct species in the herring family. It is the most common fish species from the Green River Formation and the state fossil of Wyoming.

Once in the geology program, I started learning everything I could about historical geology, paleontology, and the evolution of fishes. I took several more courses from the crafty Professor Sloan, who had hooked me in the first place. I also started visiting the source of my fossil Knightia each summer (which I will go into in more detail in chapter 3). Little did I know at the time that this site would later become my most important field site as a professional paleontologist. My interest in fossil fishes grew to include how they fit into the evolutionary network of living fishes and the anatomy of fish skeletons. I received a BS in geology after three years and continued on in a double master’s program in geology and zoology. My master’s thesis was called “The Paleontology of the Green River Formation, with a Review of the Fish Fauna.” During the years of study for my master’s degree, I had discovered much about fossils from the Green River Formation, and by 1978 I was making preparations to get my thesis published as a book.

I had learned a lot at the University of Minnesota, but there had been only so much that the professors there could teach me about fishes. I had to delve broadly and deeply into the scientific literature on fossil fishes and fish anatomy for my thesis research and found one scientist doing particularly innovative work in my particular areas of interest: Colin Patterson. Patterson was a principal scientific officer of the Museum of Natural History in London (equivalent to a curator in the United States), and he curated the world’s largest fossil fish collection (over 80,000 specimens). He had helped develop an astounding new acid-preparation technique that could make a 150-million-year-old fossil fish appear as though it had died yesterday, providing much more information for scientific analysis. His artistic reconstructive drawings of these fossils seemed to make them come to life (or at least look like fresh dissections of living species). He was also becoming a major authority in evolutionary biology. I decided to seek his advice on publishing my thesis.

I mailed Patterson a draft copy, hoping he would read it and provide some critical review. I wasn’t sure that such a world-renowned scientist would agree to do this, but to my surprise, he responded only a few weeks later! Such an immediate response was remarkable in the days when correspondence was written and posted, not sent electronically. He was extremely encouraging, saying that its publication would be a valuable contribution to the paleontological literature. He also strongly recommended that I go to New York and enroll in a PhD program in evolutionary biology under the guidance of Donn E. Rosen and Gareth (Gary) J. Nelson at the American Museum of Natural History. Rosen and Nelson were both curators in the Ichthyology (fish) Division of the museum. Nelson was at the forefront of fundamental change in the world of biological systematics, which is the study of biodiversity, classification, and evolutionary relationships. Patterson was a close, longtime colleague of both Rosen and Nelson, and he convinced them that I might be worth the trouble to take in as a student. A short time later, I received an invitation from Rosen to come to New York with a four-year fellowship covering all costs and living expenses; and so began the most intensive academic training of my life as a student.

The New York graduate program was a collaborative venture between the City University of New York and the American Museum of Natural History, where I was given an office in the museum’s Ichthyology Department. My move from the laid-back, working-class suburbs of Minneapolis to the Upper West Side of Manhattan in 1979 was quite a transition. My one-room studio apartment was on the eleventh floor of a high-rise building located at Seventieth and Broadway, only seven city blocks from the museum. The never-ending cacophony of car alarms, horns, engines, and emergency vehicle sirens eventually became white noise in my nights and mornings. I soon came to appreciate the fast-moving culture of the island of over a million and a half residents.

Donn Rosen was the paternal heart of the museum’s Ichthyology Department for the staff and graduate students. He loved the American Museum of Natural History, and he was the first person to show me how vested curators can be in training the next generation of scientists. Rosen taught me much about fish anatomy. Fossil species are usually preserved only as skeletons, so knowing the skeletal anatomy of living species enabled me to more accurately identify what I was looking at in the fossils. I also learned from him a critical technique for preparing small alcohol-preserved specimens: clearing and double staining. Two flesh-penetrating dyes color the bones red and the cartilages blue. Then the flesh is rendered completely transparent by soaking the specimen in enzymes and glycerin for many weeks to months. The process results in colored bones and cartilages clearly showing through the body. This technique can be used to produce many convenient-sized skeletons that would easily fit on a microscope stage for careful dissection and examination. While I was in New York working on my doctoral thesis I cleared and stained nearly a thousand fishes and learned to identify most of the major groups of living fishes by their skeletons. The sheer beauty of these specimens further fed my appreciation for the aesthetics and function of anatomy (see page 17).

Rosen had a subversive style of teaching. He taught his students to be unafraid of questioning scientific authority. In a course he gave on systematics, he handed out a list of assumptions that he said inhibited progress in comparative biology and evolutionary theory. The list included:

“Ultimate causes are knowable.”

“Scientists are more objective than other people.”

“Your graduate advisor and/or your distinguished visiting professor are probably right most of the time.”

He encouraged students to challenge the system, and he tried to differentiate the more empirical components of science from its more dogmatic beliefs and occasional arm waving. Science, when it works, is an evolving process and a testable method, not a book of prescribed truths. Rosen lived only to the age of fifty-seven. Nevertheless, he was highly influential in training the next generation of fish systematists, and his PhD students became curators in many of the world’s top natural history museums.1

A few months after I had moved to New York, Rosen invited me into his office to explain the lay of the academic landscape for my new PhD program. He started by telling me that there was a serious clash of ideologies centered at the American Museum of Natural History involving biological systematics. The controversy sometimes got ugly and spilled over to affect graduate students. He proceeded to explain that after my first year in the program, I would have to pass a four-part written preliminary exam for City University of New York in order to continue on for the PhD. One of those parts was controlled by professors who dogmatically followed a traditional school of systematics with the somewhat pretentious name of “evolutionary taxonomy.” This group was adamantly opposed to the school of systematics advocated by Rosen and Nelson called cladistics. The clash of systematic schools was seriously partisan and highly volatile at the time. Rosen explained that I should assume I would either fail or get an extremely low score in the part of the exam that was overseen by the traditionalists because I would be allied with my advisors and other cladists. I would need to take a philosophical stand on the test and defend my point of view, even though there would be a definite cost to doing so. Therefore I would have to give nearly perfect answers for the other three parts of the exam in order to get an overall pass. Rosen’s pep talk got my adrenaline pumping.

In preparation for the exam, I spent many long hours reading dozens of books and taking classes on systematics, philosophy of science, evolution, and scientific method. I discussed and debated scientific method with professors, visiting seminar speakers, and fellow students. I also had many hours of in-depth discussions with Nelson and Rosen. They, together with Patterson in London, were some of the most prominent figures in systematic theory and philosophy during my time in New York. Nelson, in particular, was the de facto leader of the cladistic movement.

Cladistics is a search for patterns of relationship among things based on uniquely shared characteristics.2 Such patterns are called cladograms. When used in an evolutionary context, cladistics is also called phylogenetics. Cladistic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: Curators of Natural History and Human Culture

- 1 Moving toward the Life of a Curator

- 2 Beginning a Curatorial Career

- 3 Staking Out a Field Site in Wyoming

- 4 Mexico and the Hotel NSF

- 5 Willy, Radioactive Rayfins, and the Fish Rodeo

- 6 A Dino Named SUE

- 7 Adventures of My Curatorial Colleagues from the Field

- 8 The Spirit of K-P Schmidt and the Hazards of Herpetology

- 9 Executive Management

- 10 Exhibition and the Grainger Hall of Gems

- 11 Grave Concerns

- 12 Hunting—and Conserving—Lions

- 13 Saving the Planet’s Ecosystems

- 14 Where Do We Go from Here?

- Acknowledgments

- Notes, Added Commentary, References, and Figure Credits

- Index